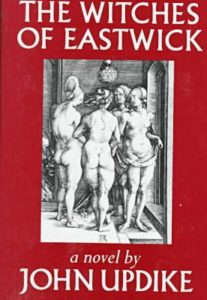

Literary Hub recently posted Margaret Atwood‘s original 1985 review of The Witches of Eastwick: “Margaret Atwood on Phallus Worship and Updike’s Bad Witches.” In it, she praised the book for its magical realism—a style, or genre, that has eluded American writers.

“These are not 1980’s Womanpower witches,” Atwood writes. “They aren’t at all interested in healing the earth, communing with the Great Goddess, or gaining Power-within (as opposed to Power-over). These are bad Witches, and Power-within, as far as they are concerned, is no good at all unless you can zap somebody with it. They are spiritual descendants of the 17th-century New England strain and go in for sabbats, sticking pins in wax images, kissing the Devil’s backside and phallus worship; this latter though—since it is Updike—is qualified worship.

After describing the book’s premise she writes, “This may sound like an unpromising framework for a serious novelist. Has Mr. Updike entered second childhood and reverted to Rosemary’s babyland? I don’t think so. For one thing, The Witches of Eastwick is too well done. Like Van Horne, Mr. Updike has always wondered what it would be like to be a woman, and his witches give him a lot of scope for this fantasy. Lexa in particular, who is the oldest, the plumpest, the kindest and the closest to Nature, is a fitting vehicle for some of his most breathtaking similes. In line of descent, he is perhaps closer than any other living American writer to the Puritan view of Nature as a lexicon written by God, but in hieroglyphs, so that unending translation is needed. Mr. Updike’s prose, here more than ever, is a welter of suggestive metaphors and cross-references, which constantly point toward a meaning constantly evasive.

After describing the book’s premise she writes, “This may sound like an unpromising framework for a serious novelist. Has Mr. Updike entered second childhood and reverted to Rosemary’s babyland? I don’t think so. For one thing, The Witches of Eastwick is too well done. Like Van Horne, Mr. Updike has always wondered what it would be like to be a woman, and his witches give him a lot of scope for this fantasy. Lexa in particular, who is the oldest, the plumpest, the kindest and the closest to Nature, is a fitting vehicle for some of his most breathtaking similes. In line of descent, he is perhaps closer than any other living American writer to the Puritan view of Nature as a lexicon written by God, but in hieroglyphs, so that unending translation is needed. Mr. Updike’s prose, here more than ever, is a welter of suggestive metaphors and cross-references, which constantly point toward a meaning constantly evasive.

“His version of witchcraft is closely tied to both carnality and mortality. Magic is hope in the face of inevitable decay. The houses and the furniture molder, and so do the people. The portrait of Felicia Gabriel, victim wife and degenerate after-image of the one-time ‘peppy’ American cheerleading sweetheart, is gruesomely convincing. Bodies are described in loving detail, down to the last tuft, wart, wrinkle and bit of food stuck in the teeth. No one is better than Mr. Updike at conveying the sadness of the sexual, the melancholy of motel affairs—’amiable human awkwardness,’ Lexa calls it. This is a book that redefines magic realism.

Later, she concludes, “Much of The Witches of Eastwick is satire, some of it literary playfulness and some plain bitchery. It could be that any attempt to analyze further would be like taking an elephant gun to a puff pastry: An Updike should not mean but be. But again, I don’t think so. What a culture has to say about witchcraft, whether in jest or in earnest, has a lot to do with its views of sexuality and power, and especially with the apportioning of powers between the sexes. The witches were burned not because they were pitied but because they were feared. . . .

“Mr. Updike provides no blameless way of being female. Hackles will rise, the word ‘backlash’ will be spoken; but anyone speaking it should look at the men in this book, who, while proclaiming their individual emptiness, are collectively, offstage, blowing up Vietnam. That’s male magic. Men, say the witches, more than once, are full of rage because they can’t make babies, and even male babies have at their center ‘that aggressive vacuum.’ Shazam indeed!”

near definitive sounding response to a Seattle Review of Books reader who was upset by “all the harassing men in the media lately” and had written, “At some point, we have to realize that a writer who writes about treating women horribly is probably pretty likely to treat women horribly, right? I mean, I’m not saying that they should be locked up or anything, but women would be smart to avoid authors who write approvingly about being monstrous harassers, wouldn’t they?”

near definitive sounding response to a Seattle Review of Books reader who was upset by “all the harassing men in the media lately” and had written, “At some point, we have to realize that a writer who writes about treating women horribly is probably pretty likely to treat women horribly, right? I mean, I’m not saying that they should be locked up or anything, but women would be smart to avoid authors who write approvingly about being monstrous harassers, wouldn’t they?”