Five Books, a site that asks writers to share five books that influenced them in some way, recently published the choices by Sam Tanenhaus, Ian McEwan, and William Boyd.

Five Books, a site that asks writers to share five books that influenced them in some way, recently published the choices by Sam Tanenhaus, Ian McEwan, and William Boyd.

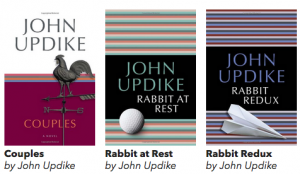

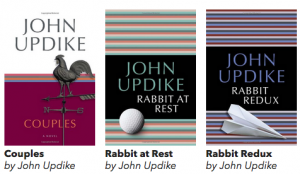

Tanenhaus named Rabbit Redux as one of his five influential books, while McEwan and Boyd cited Rabbit at Rest and Couples, respectively.

Tanenhaus cited Rabbit Redux as a great example of literature describing what he called “the peak period of conservatism as an intellectual force in American life” from 1967-73. “It’s the second of his Rabbit tetralogy, and generally the least admired today. The books themselves constitute a great classic in American literature, maybe the greatest of our period,” Tanenhaus said. “The genius of Updike is that he throws himself and his characters into the middle of the controversies of the day. So Rabbit himself smokes pot and has sex with an 18-year-old runaway who comes from a wealthy family in Connecticut. He lets a black militant live in his house. He’s drawn to all the forces that he is appalled by. And that’s the genius of fiction—instead of lecturing us about all of this, Updike tries to bring it to life from many perspectives, and makes it feel very concrete.”

McEwan selected Rabbit at Rest as one of his five books. “Updike has been a very important writer for me, the one I’ve admired most, read most, and returned to most often,” said McEwan, who will deliver keynote remarks at the Fifth Biennial John Updike Society Conference hosted by the Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade, June 1-5 2018. “I think some of the descriptions of sex in Updike are extraordinary. I could never follow him down his route because his gift is one I’ve never hoped to emulate, which is the visual. In a sense he almost debunks or destroys the think he’s describing, because of his clinical eye, but it does take my breath away. In this realm he’s a master of the hyper-real.”

Boyd said that Updike was an inspiration because of his work ethic and productivity. “So when I’m writing a novel, I write seven days a week until it’s finished,” he said. But he doesn’t agree with McEwan that Updike was the greatest novelist writing in English at the time of his death in 2009. “I think Updike was a brilliant novelist and stylist and also a brilliant critic. But I gave up. I couldn’t keep up with Updike. I think that the short stories are his great legacy. I think the novels are all rather uneven and not fully achieved, with the possible exception of Couples. But Couples is another one of those books that I read at a very young age and it blew me away. Again, I must have been 19 or so when I read it, and for me it was like a window being opened onto the adult world, a world I was about to enter. I suddenly thought that this man understands human nature and the human condition in a way that I had never encountered before.

“That said, a lot of people regard Couples as his least successful novel because it seems overly preoccupied with sexual shenanigans in New England. I’ve gone back and re-read Couples and it holds up, for me, in ways that Catch-22 doesn’t. It’s a brilliantly well-written and observed book. But it’s relevance to me—and this is why I put it on the list—is because at the time I read it, veils were stripped from my eyes. I saw the world differently as a result of reading the book. It’s a great experience when that happens to you.”

See the full list and read the full interviews (links provided)