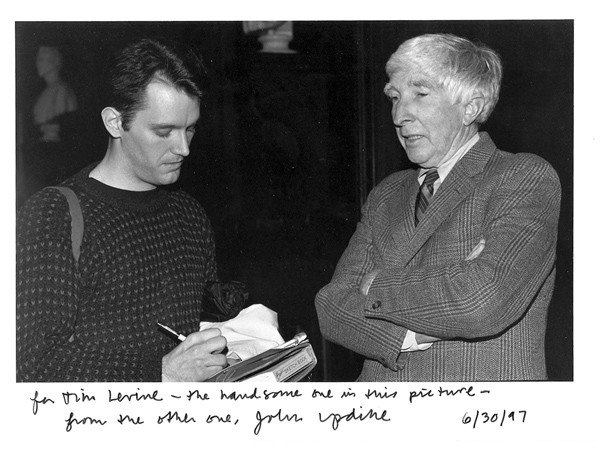

As Charles McGrath explains in an essay on “Roth/Updike” that was published in the Autumn 2019 edition of The Hudson Review, he had the privilege of knowing John Updike well enough to play golf with him and Philip Roth enough to visit him in his home. Those privileges came to him because he was a literary insider, one whose essays appeared in The New Yorker (where he was deputy editor) and The New York Times Book Review (which he formerly edited).

As Charles McGrath explains in an essay on “Roth/Updike” that was published in the Autumn 2019 edition of The Hudson Review, he had the privilege of knowing John Updike well enough to play golf with him and Philip Roth enough to visit him in his home. Those privileges came to him because he was a literary insider, one whose essays appeared in The New Yorker (where he was deputy editor) and The New York Times Book Review (which he formerly edited).

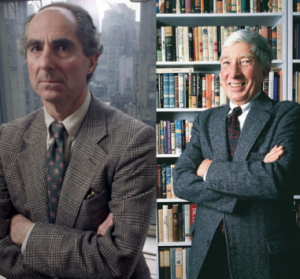

His thoughtful consideration and comparison is perhaps the best essay written on the topic of Updike and Roth. Reading it, you get a pretty fair summary of each writer’s career but also an assessment of their relationship: “They weren’t enemies, but neither were they friends, exactly. They were rivals who also happened to be mutual admirers—two of America’s greatest living writers, peering over each other’s shoulders.”

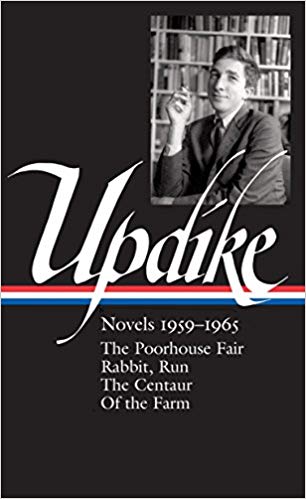

McGrath doesn’t shy away from assessing Updike’s and Roth’s careers, either. “Overnight, Roth and Updike became the two dirtiest book writers in America, or the two dirtiest with serious literary credentials. Then, in mid-career, each of them wrote a four-volume masterwork about a single character—Zuckerman in Roth’s case, Rabbit in Updike’s.”

“The two men weren’t in lockstep, and they weren’t imitating each other, certainly, but each was reading the other—with interest, admiration, maybe a tinge of envy—and surely they were both aware that each of them was assembling a major body of work and that (with the possible exception of Saul Bellow and Toni Morrison) no one else in America was writing at the same level.”

Continuing with a horse race analogy, McGrath writes,”Updike shot out in front with the first two Rabbit books; then, with The Ghost Writer, Roth caught up and even edged ahead a bit, before stumbling a little in mid-career while Updike, with the second two Rabbit books, took a big lead, practically lapping Roth. Then, just when Roth seemed to be out of gas, he got a second wind—probably the greatest late-career burst in all of American literature—with Sabbath’s Theater and the American Trilogy, and now Updike was struggling to catch up.”

Those assessments are wonderful, but it’s McGrath’s insightful perceptions of the two writers that makes this essay so poignantly powerful. He misses them and their book-a-year regimen, and so do many readers.

Read the full essay