Blogger Mia Savant posted a Ponder Savant entry on “Jackson Pollock and Other Poems by Abigail George” that includes the Pollock poem and also poems dedicated to John Updike and Georgia O’Keeffe. Here’s the Updike poem:

Blogger Mia Savant posted a Ponder Savant entry on “Jackson Pollock and Other Poems by Abigail George” that includes the Pollock poem and also poems dedicated to John Updike and Georgia O’Keeffe. Here’s the Updike poem:

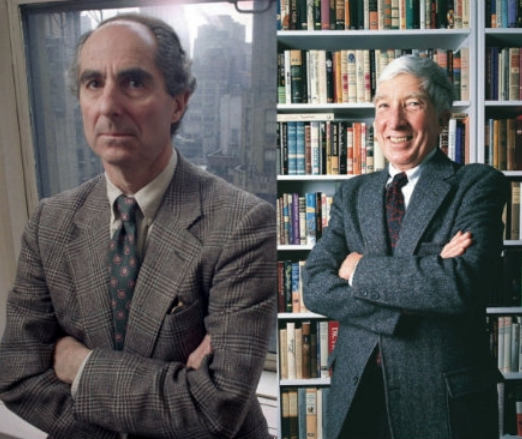

John Updike

He writes. He writes. He writes. He writes. And it feels

as if he is writing to me. There’s the letting go of sadness,

the letting go of emptiness, of the swamp ape in the land.

Lines written after communion, and as I write this, I am

aware of growing older, men growing colder. And this

afternoon, the dust of it, the milky warmth of it loose like

flowers upon me fastening their hold on me, removes the

oppression that I know from all of life. Youth is no longer

on my side. The bloom of youth. Wasteland has become a

part of my identity. I am a bird. A rejected starling. To age

sometimes feels as if you are moving epic mountains. Valleys

that sing with the force of winds, human beings, the sun.

And he is beautiful. And he is kind. And he is the man facing

loneliness, and the emptiness of the day. And I am the woman

facing loneliness, and the emptiness of the day. But how

can you be lonely if you are surrounded by so many people.

I want to be those people, if only to be in your presence a

little while longer. Death is gorgeous, but life is even more so.

I have become weary of fighting wars. Of the threshold of

waiting. And so, I let go of solitude at the beach. I see my mother’s

face in every horizon. She is my sun. And the man makes

a path where there is no path before. The minority of the day

longs for power. The light reckons it has more sway over

the clouds. And there’s ecstasy in the shark, in his heart with

a head full of winter. Freedom is his mother tongue lost in

translation of the being of the trinity. Tender is the night.

The clock strains itself. Its forward motion. Its song. Its lull

during the figuring of the daylight. He’s my knight but he

doesn’t know it. He makes me forget about my grief, loss, my loss,

the measure of my grief. Driftwood comes to the beach and

lays there like a beached whale. Not stirring, but like some

autumn life, something about life is resurrected again, and the

powerful hands of the sea become my own. Between the grass

and the men, there is an innocent logic. I don’t talk to anyone,

and no one talks to me. It is Tuesday. Late. I think you can

see the despair in my eyes. The kiss of hardship in my hands.

It always comes back to that, doesn’t it somehow. The hands

The hands. The hands. Symbolic of something, or other it seems.

Wednesday morning. It is early. After twelve in the morning,

and I can’t sleep. For the life of me I can’t sleep. Between the

two of us, he’s the teacher. There is a singing sound in his voice.

I don’t know why I can’t read his mind anymore. There’s

confusion in forgetting that becomes a secret. Almost a contract

between two people. And when I think of him, I think of love

and Brazil, love and couples. And there’s a silent call from a

remote kind of land, and ignorance is a cold shroud. Some

things are born helpless in a world of assembled images, and

how quickly some people go mad with grief (like me), dream

of grief (like me), sleep with grief on their heart (like me). Speak

to me before all speech is gone. This image, or perhaps another.

His face is made up of invisible threads. Each more handsome

than the last. And my face becomes, turns into the face of love.

Abigail George is a Pushcart Prize-winning poet, essayist, writer, and novelist . She received four grants from the National Arts Council in Johannesburg, the Centre for the Book in Cape Town and ECPACC in East London. She is the author of 15 books, including two poetry chapbooks forthcoming in 2020: Of Bloom and Smoke (Mwanaka Media and Publishing) and The Anatomy of Melancholy (Praxis Magazine).

Bill Vallicella (aka Maverick Philosopher) writes, “Given what we know from yesterday’s Updike entry, the suspicion obtrudes that, while Updike clearly understands the Resurrection as orthodoxy understands it, his interest in it is merely aesthetic in Kierkegaard’s sense, and not ethical in the Dane’s sense, which suspicion comports well with the charge that Updike radically divorced Christian theology from Christian ethics.

Bill Vallicella (aka Maverick Philosopher) writes, “Given what we know from yesterday’s Updike entry, the suspicion obtrudes that, while Updike clearly understands the Resurrection as orthodoxy understands it, his interest in it is merely aesthetic in Kierkegaard’s sense, and not ethical in the Dane’s sense, which suspicion comports well with the charge that Updike radically divorced Christian theology from Christian ethics.