Editor’s note: This story was published in the June 2021 Class of 1971 newsletter “Remembering our College Days” and is reprinted here with the permission of the author.

Guest post by Judith Schulz, Class of 1971

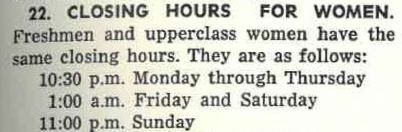

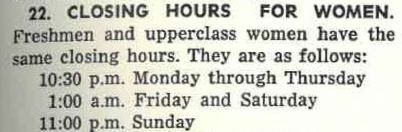

In our 1967-68 student handbook they were called CLOSING HOURS. That is when the dorm entrance doors were closed, and Locked. Hours really meant “curfew.” It was a form of in loco parentis.

I didn’t think anything about these rules when I arrived at IWU as a freshman in Sept 1967 at age 18. Those were the rules, so those were the rules. Both the 1967 and 1968 IWU student handbooks had the same closing hours listed for Women (but not for men students!) (Men had NO closing hours.)

(click any image in this post to enlarge)

WOMEN STUDENTS HAD TO BE INSIDE BY 10:30 pm

On weeknights we had to be inside our residence hall/dorm by 10:30 pm, Friday & Saturday by 1 am, Sunday night by 11 pm. It didn’t matter to me anyhow during my first semester as I was tired, had homework or was working late hours in the Dug Out as a short order cook/ order taker. Men did not have any of these rules, just we women. (hmmm.) Obvious double standard. HOURS were an issue at many colleges around the USA at the time.

DORM BED CHECK?

I lived in Pfeiffer Hall, second floor East wing and right after 10:30 there was a “bed check” where an assigned student living in the dorm came around and checked your name against the list to make sure you were in your room.… we didn’t actually to have to be “in bed.” Just writing this on paper, I mean on the computer, makes we wonder why we didn’t question this.

AFTER 10:30 pm

Sometimes after the bed check there would be a “house” meeting, party, holiday activity or gathering in the first-floor lounge. (I see they called it a “parlor” in the handbook, but we called it “the Lounge.”) These after- hours gatherings helped us to make friends and become part of the residence hall “family,” but it also functioned to distract you from the fact that we were under a strict curfew, even though we were of adult age.

IF YOU WERE LATE: LATE MINUTES!

And if you were late coming into your residence hall, after hours, “late minutes” resulted in punishment.

One Saturday night I signed out for a 2 o’clock, but was late just 2 minutes getting back inside Pfeiffer Hall. This was considered very serious. (And whoever was working the desk had to wait up until you came in.)

– Pfeiffer’s House Council voted to restrict me to the dorm for the entire next weekend, only being allowed to go for a short visit to the commons to eat meals. It was called “dorm pro” for probation. I was also required to contact the house mother regularly, proving I was in the dorm. I thought this restriction was extreme and absurd, so I called the house mother every hour throughout the weekend and even late into the night to report in, hoping frequent calls would make a point. (They did.)

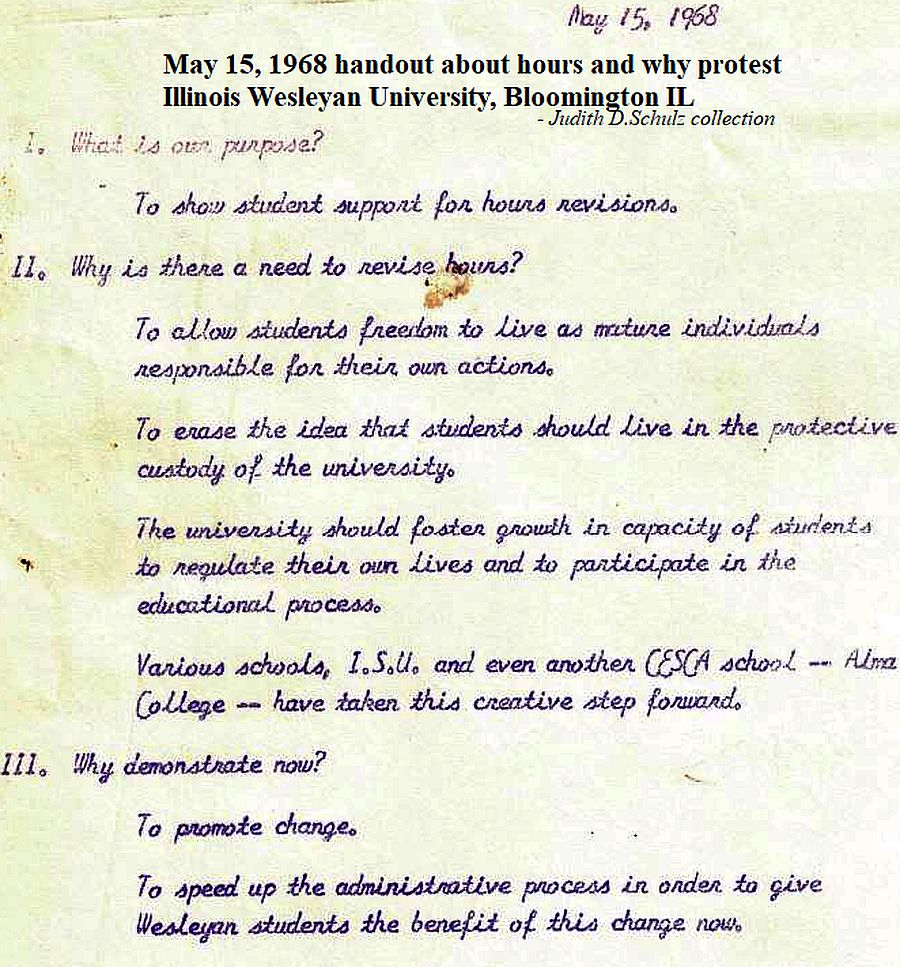

IN THE SPRING of 1968, the idea of changing or getting rid of “hours” was a topic of discussion everywhere. Was the university really supposed to be in the role of parenting, and supervising students who were of age? Student Senate made motions, there were “university studies” and a growing frustration among students.

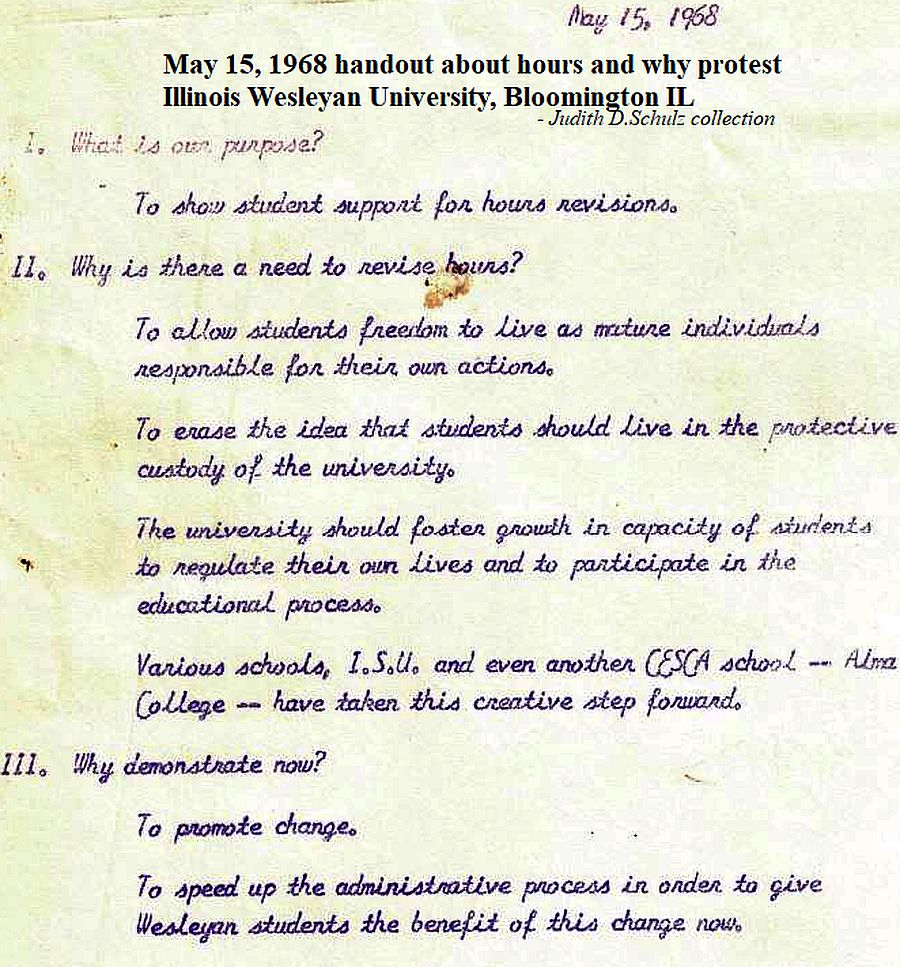

May 15, 1968 handout, Q&A about hours & a protest

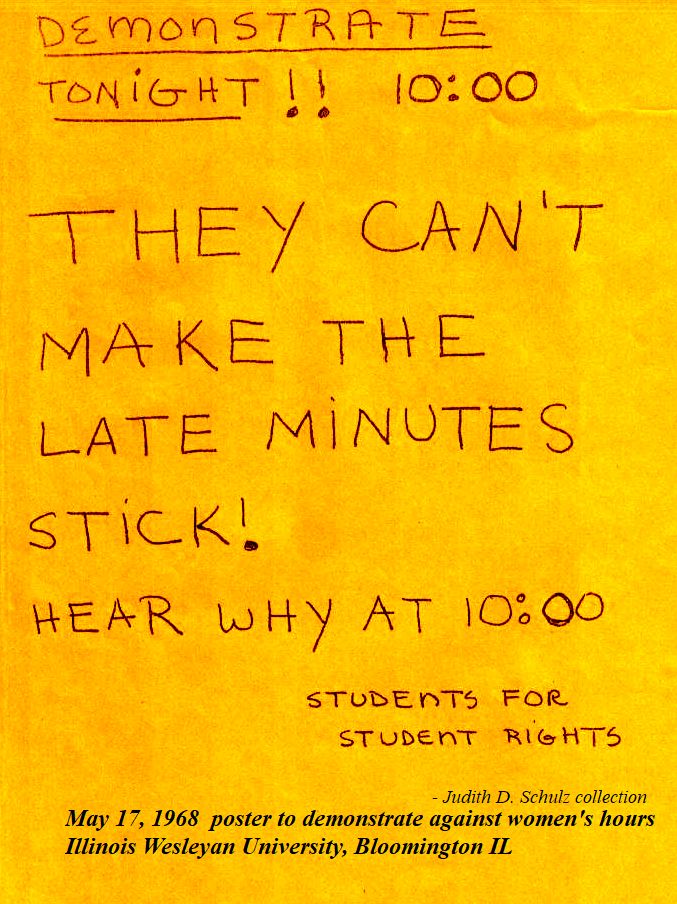

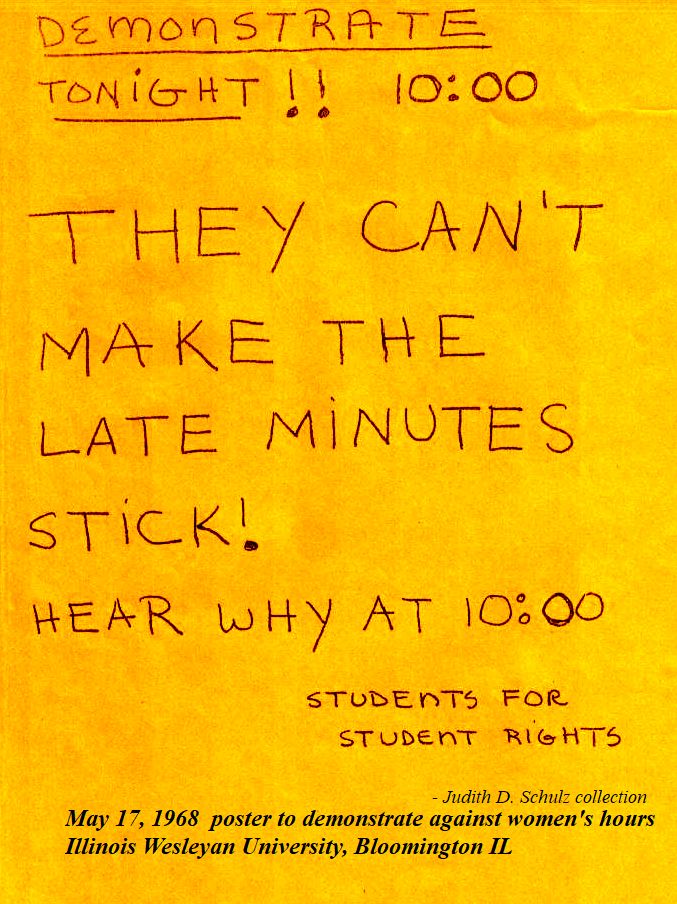

POSTERS were hung up around campus and talk of having an after-hours protest was everywhere. The protest was to be at 10 pm Thursday, May 17, 1968 and last until 11:30 pm—AFTER HOURS!— We would definitely be breaking the rules! And think of it: more than 60 LATE MINUTES?

While I agreed 100% with the cause and the protest, it made me nervous. I knew what late minutes meant, and we would all be more than 60 minutes late if we attended the protest.

Note: I have this original handout (above) and poster (next image) 8.5×11” paper. Copies were made on an old fashion ditto duplicator machine in purple lettering. (not old fashion at the time.)

May 17, 1968 Original poster, 8.5×11” ditto

That night I heard many students encouraging others to attend saying “they can’t make the late minutes stick” which matched the posters that were also all over campus.

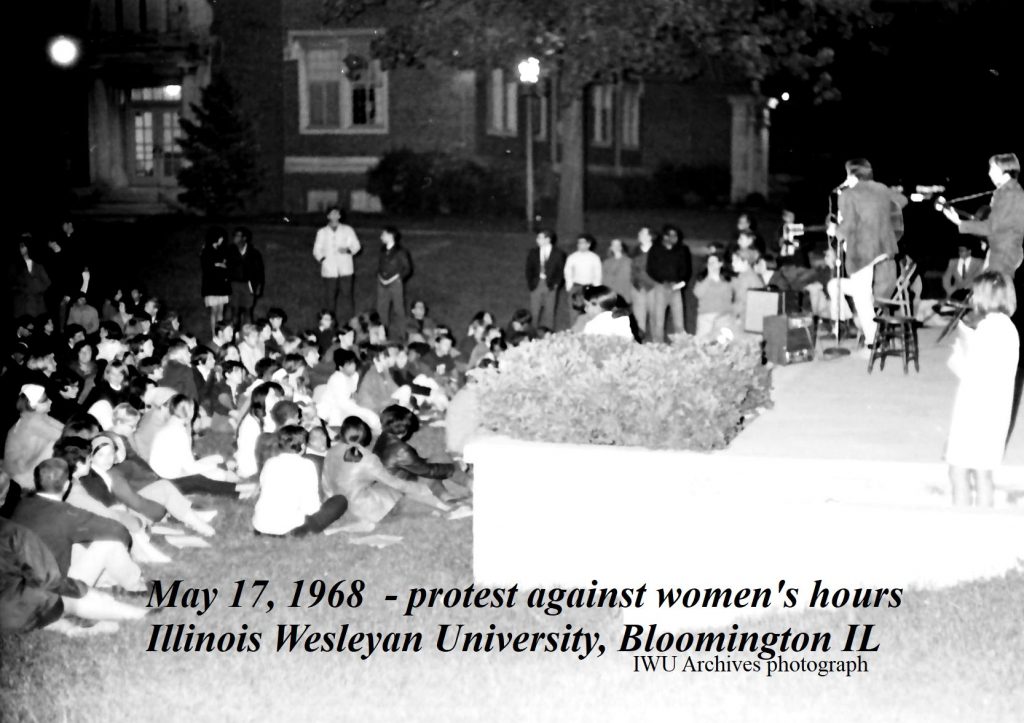

It was a time to think for yourself, and support what you believed in. I was still very nervous walking over, even with so many others, to the outdoor stage of McPherson. I recall Wenona Whitfield encouraging everyone in the group I was with while walking over to the protest.

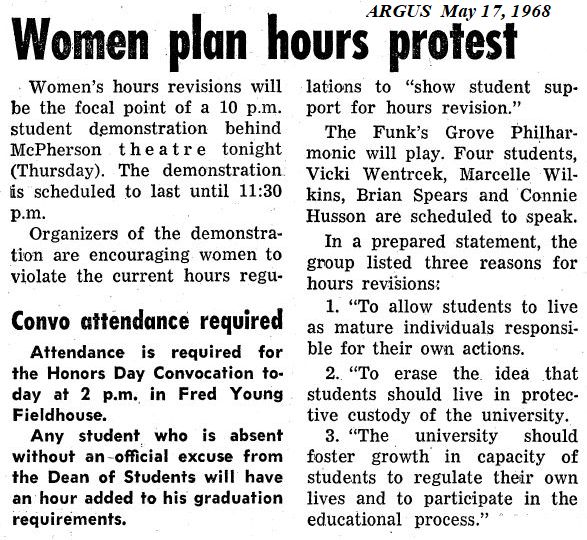

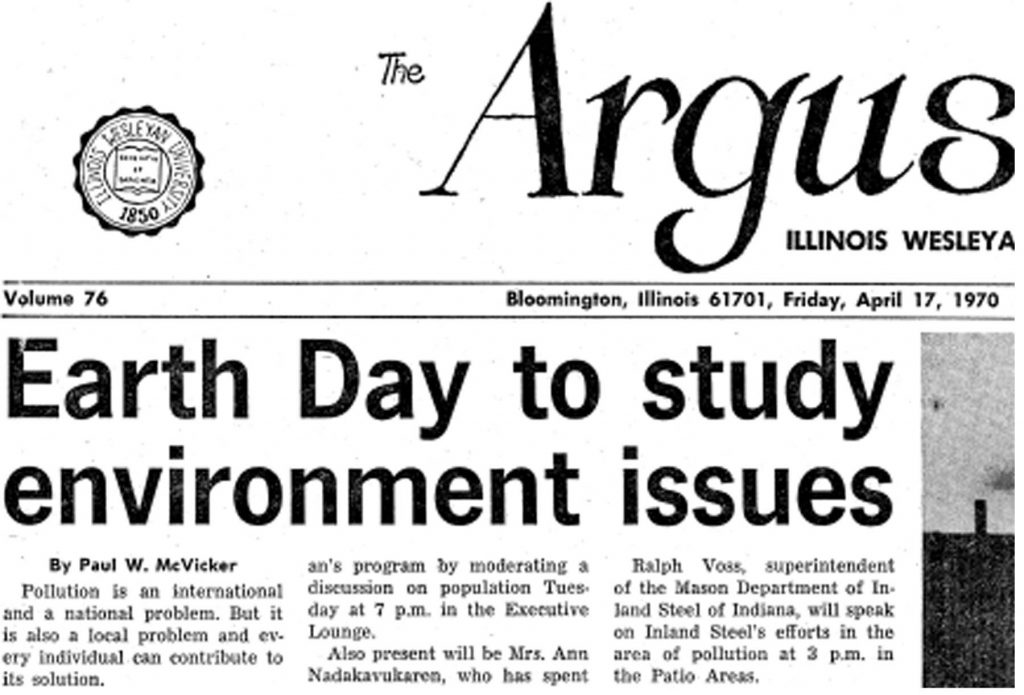

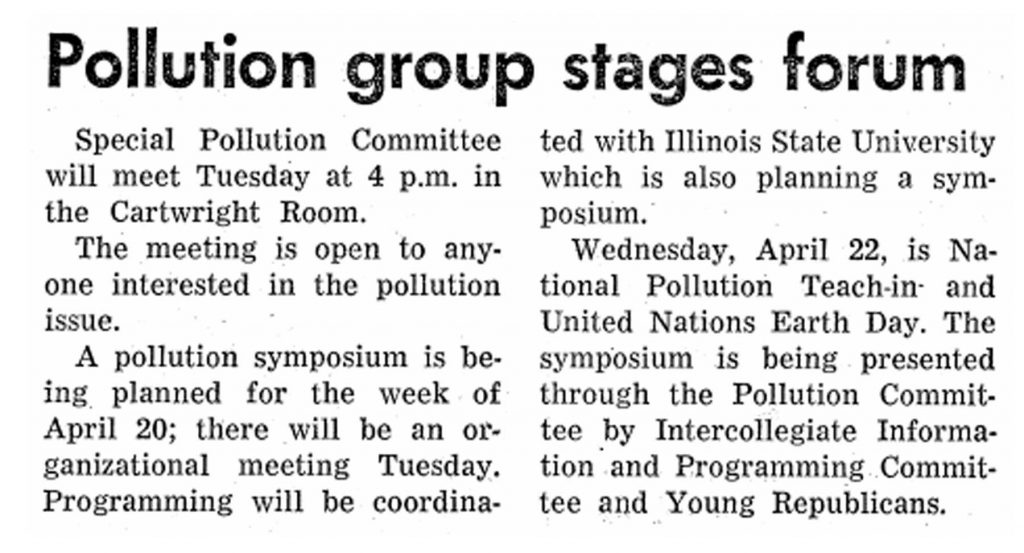

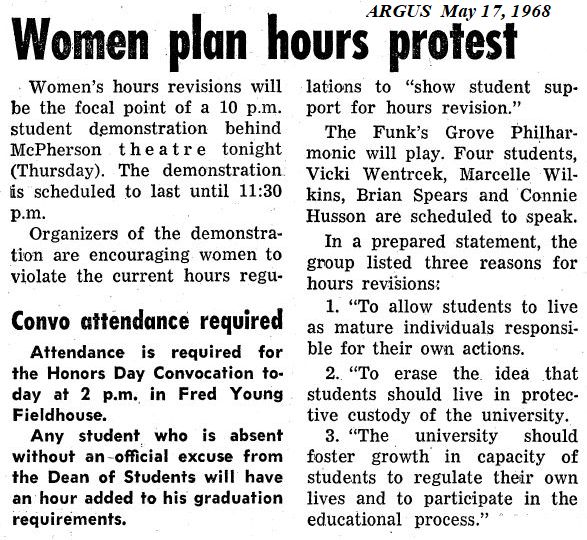

IWU ARGUS newspaper story May 17, 1968 – note both stories

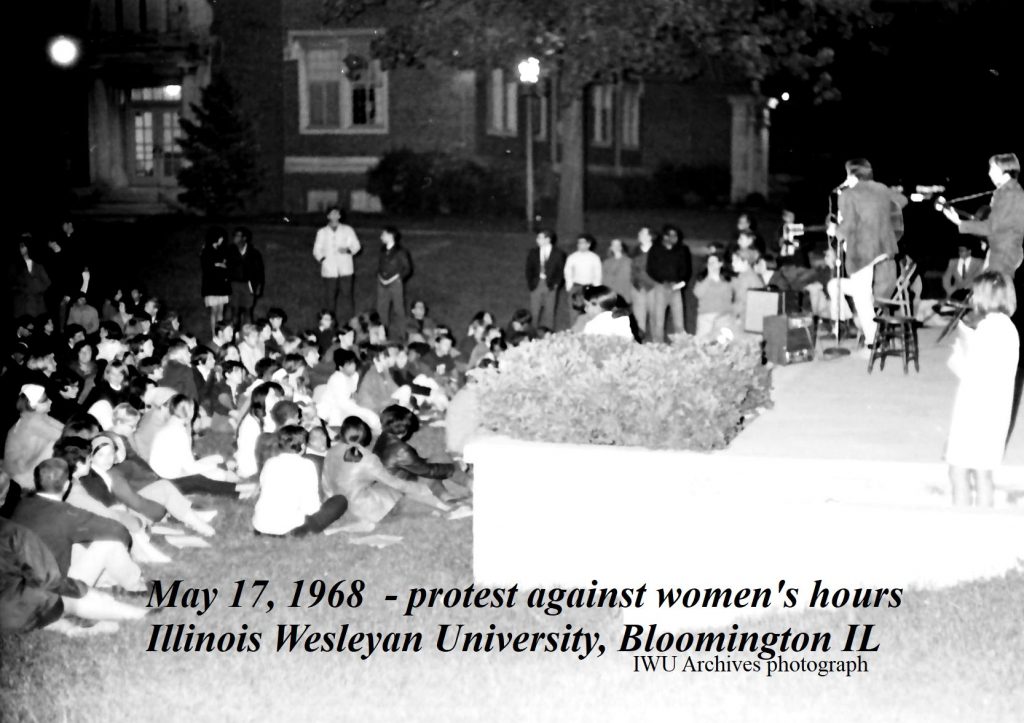

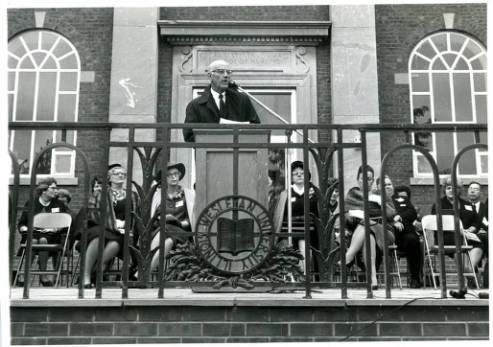

May 17, 1968 Hours Protest, after hours- IWU Archives

Women students and men students attended the hours protest, even a few IWU staff. There was a band, and 4 students spoke: Vicki Wentrcek, Marcelle Wilkins, Brian Spears and Connie Husson.

WERE YOU THERE? Did you stay out 1 hour past “Hours” and get any “late minutes?” Please share your stories and memories about hours in the reply box below.

~ Watch for the stories of what happened next…..

what changed and what didn’t.

~ SEE you at our 50th Class of 1971 reunion in October 2021!

The actual posters shown here, MORE artifacts and photographs from this time will be on display at our 50th IWU Class of 1971 reunion October 2021.

~author Judith Schulz, Pfeiffer Hall resident, IWU class of 1971(and in the crowd in the photo above) written June 2021 for the Class of 1971 Alumni newsletter

Research info from Judi Kasper Ballard, Mark Sheldon, IWU archivist Meg Miner, Vicki Wenger Warren, and Judith Schulz

Images from Judith Schulz’s collection and IWU Archives