Robert Matzen published a piece on his blog titled “Umbrella Man,” in which he talks about maybe writing about the fate of TWA Flight 3 and recalls the book Six Seconds in Dallas buy Josiah Thompson and John Updike’s response to reading it.

Robert Matzen published a piece on his blog titled “Umbrella Man,” in which he talks about maybe writing about the fate of TWA Flight 3 and recalls the book Six Seconds in Dallas buy Josiah Thompson and John Updike’s response to reading it.

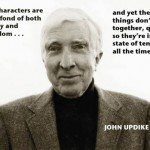

“Six Seconds in Dallas appeared in 1967, nearly 50 years ago, and now Tink [Thompson] is advanced in age, but he popped up in a fascinating Youtube video that had been forwarded to me, and I delighted in the concept he described—a concept developed by Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist John Updike in response to reading Thompson’s book.”

“The truth about those seconds in Dallas is especially elusive,” Updike wrote in 1967; “the search for it seems to demonstrate how perilously empiricism verges on magic.”

And now Thompson is quoting Updike. “‘In historical research,’ says Thompson of the Updike position, ‘there may be a dimension similar to the quantum dimension in physical reality. If you put any event under a microscope, you will find a whole dimension of completely weird, incredible things going on. It’s as if there’s the macro level of historical research, where things sort of obey natural laws and the usual things happen and unusual things don’t happen, and then there’s this other level where everything is really weird.'”

Blogger Matzen writes, “Seeing the YouTube video and reading Updike’s original think piece [in The New Yorker] hit me like a pumpkin to the head because I had spent years trying to sort out the circumstances leading up to the crash of Flight 3— circumstances that should have been sortable and explainable but read like Fiction 101. The crash of Flight 3 and the reasons why Carole Lombard died on the plane with 21 others fit perfectly with Updike’s subatomic realm because the more we apply the rules of man’s physical world, the less the story makes sense.”

Here’s the entire article: “Umbrella Man.”