It was a long time coming, and Linda George Grimes, the woman who spearheaded the campaign to honor John Updike with a plaque, was not there to see the fruits of her labors. She passed away in March at age 66. But the Ipswich Historical Commission took over and Ipswich finally recognized its most famous resident on April 28, 2023.

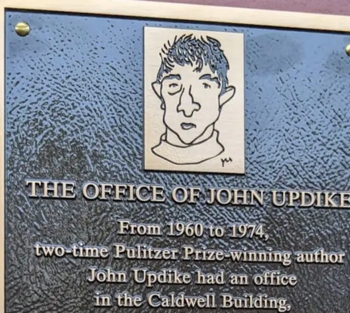

The plaque, which was mounted next to the Caldwell Building entrance that Updike took to reach his second-floor office, reads: “From 1960 to 1974, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author John Updike had an office in the Caldwell Building, where he wrote many acclaimed literary works, including ‘A&P,’ Bech: A Book, The Centaur, Couples, ‘Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,’ Midpoint, A Month of Sundays, Of the Farm and Rabbit Redux.”

Couples, a 1968 novel, caused a stir in Ipswich because of its scandalous content: wife swapping. Some locals recognized themselves in the book, and the Updike family decided to spend the next year in London. Fittingly, there was just the slightest hint of scandalous behavior at the plaque unveiling, as grandchildren Trevor and Sawyer Updike proudly posed alongside the plaque to show matching tattoos of the self-portrait caricature their grandfather had drawn to accompany his Paris Review interview. The tattoos were on their thighs, which, of course, required that their trousers be dropped in order to show them off.

Trevor Meek covered the event for The Local News. Read the full story and see photos of the event.