The latest publication to include Adam Begley’s biography, Updike, on their Best of 2014 lists is The DC Spotlight Newspaper, which numbers it among their “Books To Know – Top 10 List – September 2014.”

4. Updike

By Adam Begley, April 2014

Updike is Adam Begley’s masterful, much-anticipated biography of one of the most celebrated figures in American literature: Pulitzer Prize-winning author John Updike—a candid, intimate, and richly detailed look at his life and work.

In this magisterial biography, Adam Begley offers an illuminating portrait of John Updike, the acclaimed novelist, poet, short-story writer, and critic who saw himself as a literary spy in small-town and suburban America, who dedicated himself to the task of transcribing “middleness with all its grits, bumps and anonymities.”

Updike explores the stages of the writer’s pilgrim’s progress: his beloved home turf of Berks County, Pennsylvania; his escape to Harvard; his brief, busy working life as the golden boy at The New Yorker; his family years in suburban Ipswich, Massachusetts; his extensive travel abroad; and his retreat to another Massachusetts town, Beverly Farms, where he remained until his death in 2009. Drawing from in-depth research as well as interviews with the writer’s colleagues, friends, and family, Begley explores how Updike’s fiction was shaped by his tumultuous personal life—including his enduring religious faith, his two marriages, and his first-hand experience of the “adulterous society” he was credited with exposing in the bestselling Couples.

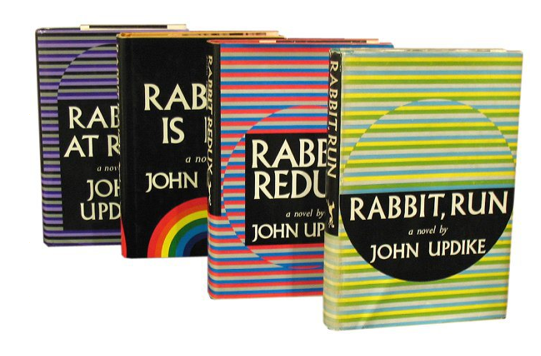

With a sharp critical sensibility that lends depth and originality to his analysis, Begley probes Updike’s best-loved works—from Pigeon Feathers to The Witches of Eastwick to the Rabbit tetralogy—and reveals a surprising and deeply complex character fraught with contradictions: a kind man with a vicious wit, a gregarious charmer who was ruthlessly competitive, a private person compelled to spill his secrets on the printed page. Updike offers an admiring yet balanced look at this national treasure, a master whose writing continues to resonate like no one else’s.