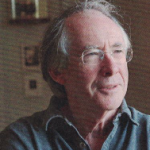

Today John Updike (1932-2009) would have celebrated his 85th birthday, and notable among the remembrances published in commemoration is one by Steve King, written, fittingly, for a books site: Barnes & Noble.

Today John Updike (1932-2009) would have celebrated his 85th birthday, and notable among the remembrances published in commemoration is one by Steve King, written, fittingly, for a books site: Barnes & Noble.

In “Something Intricate and Fierce,” King begins with a quote from Updike and follows with this quote from reviewer Jonathan Raban: “Rabbit at Rest is one of the very few modern novels in English . . . that one can set beside the work of Dickens, Thackeray, George Eliot, Joyce and not feel the draft.”

Birthday tributes are a testament to Updike’s cultural importance, but King’s post illustrates something that would make Updike smile if he were still around to blow out the candles: that he has political relevance, something that in his lifetime, ironically, critics never appreciated.

“Whatever Updike’s own politics—biographer Begley notes that Updike on his deathbed rejoiced at President Obama’s inauguration—some commentators say that Updike lives on as spokesman for embattled Middle Americans, whose current angst and anger he saw coming.” And King concludes with a quote from Charles McElwee, written for The American Conservative magazine: “‘Revisiting Updike’s Rabbit novels is a rendezvous with prescience, for no collection of postwar fiction could help us better understand how working-class populism—in the form of Donald Trump—prevailed on Election Day 2016.”

Updike—and irony—are still very much alive.

Happy 85th, Mr. Updike!