The New Yorker recently posted an Updike essay on “Christmas Cards” that first appeared in a December 22, 1997 issue. In it, Updike recalls Christmas at the Philadelphia Avenue house, where the “taste of Christmas in the little Pennsylvania town of Shillington—one of the more penetrating in my life’s bolted meals—was compounded of chocolate-flavored piety, as sweetly standardized as Hershey’s Kisses, and a tart, refreshed awareness of where one stood on the socioeconomic scale.”

Author Archives: James Plath

Gallery includes fun Updike photo

If you’re in the Boston area you might check out the John Goodman show, “HomeTown,” now on display at the Miller Yezerski Gallery through February 3.

If you’re in the Boston area you might check out the John Goodman show, “HomeTown,” now on display at the Miller Yezerski Gallery through February 3.

Fifty-three photographs are featured, including a portrait of Barrack Obama when he was still a Harvard Law student and a fun shot of John Updike balancing a sideways-turned hat on his head.

The gallery is located at 460 Harrison Ave. in Boston, and you can phone (617) 262-0550 for more information.

You can see the Obama and Updike photos in a Boston Globe story by Mark Feeney.

Essayist on Rabbit, Male Alienation, and the Fear of Intimacy

Blogger-essayist Chris Schumerth recently posted an essay he wrote on “John Updike’s Rabbit, Male Alienation, and the Fear of Intimacy.”

Although Schumerth admits he’s only read Rabbit, Run, he incorporates the opinions of scholars and understands that “To read Rabbit, Run as solely a condemnation of Rabbit’s sexual infidelities cheapens does [sic] a disservice to Rabbit’s psyche and the moral dilemma involved.”

Essayist describes the essence of Updike

Daniel Ross Goodman wrote an essay for The Witherspoon Institute’s Public Discourse titled “Updike’s Wager: Brilliance, Doubt, and the Miracle of Existence” that gets right to the heart of the matter: what made Updike’s life and literature “approachable.”

“Very few literary lives are comparable to that of John Updike,” Goodman writes, but asserts that “Updike, despite occasional flourishes in his Rabbit novels, lacks the fierce passion that animated the life and literature of his contemporary (and erstwhile rival) Philip Roth. Yet both Updike’s career and Begley’s extremely well-written book are, unfortunately, largely boring. They are boring in their brilliance, boring in their monotonous excellence, and boring in their clinical perfection of form. To read Updike—and to read about his life—is to observe an incessant stream of perfection and good fortune: perfectly placed word; perfect job placement; fluid story; unimpeachable novel; immaculately executed prose; novelist taking his place among the finest of the realist tradition. We yearn for Updike to be challenged, just as we exult in Rabbit Angstrom’s rare displays of tempestuous rage.

“Very few literary lives are comparable to that of John Updike,” Goodman writes, but asserts that “Updike, despite occasional flourishes in his Rabbit novels, lacks the fierce passion that animated the life and literature of his contemporary (and erstwhile rival) Philip Roth. Yet both Updike’s career and Begley’s extremely well-written book are, unfortunately, largely boring. They are boring in their brilliance, boring in their monotonous excellence, and boring in their clinical perfection of form. To read Updike—and to read about his life—is to observe an incessant stream of perfection and good fortune: perfectly placed word; perfect job placement; fluid story; unimpeachable novel; immaculately executed prose; novelist taking his place among the finest of the realist tradition. We yearn for Updike to be challenged, just as we exult in Rabbit Angstrom’s rare displays of tempestuous rage.

“Why the lack of intense passion in Updike? Why does Harold Bloom’s stinging critique of Updike—”a minor novelist with a major style”—still retain its pique? Perhaps it was because Updike did not experience the deep suffering of many other literary geniuses.”

Goodman nonetheless concludes that Updike, compared to a host of literary luminaries, “may be the most intellectually curious writer of them all (George Eliot excepted, of course),” and it is “his extreme existential angst that makes Updike’s life and literature approachable. For who among us does not wonder about the meaning of our lives, the value of religion, and the nature of the universe? This element of existential exploration imparts a compelling, fascinating dimension to his work.”

Read the whole essay here.

JUS Facebook page reaches 770 likes

That’s right. The John Updike Society Facebook page has reached 770 “likes,” which is more than three times the number of society members.

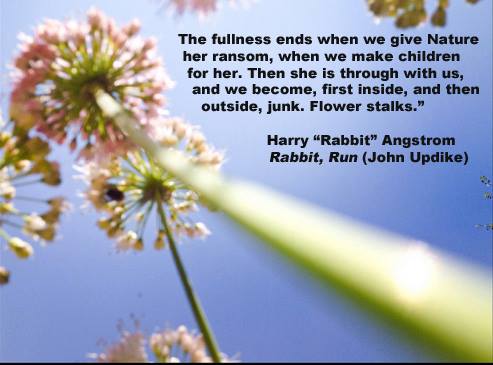

All of the stories from this website are posted on Facebook, but there are also memes (like the one below) posted on the Facebook page that aren’t posted on this site. So if you don’t want to be left out and if you “do” Facebook, remember to “like” the John Updike Society page.

More Best Books lists for Begley

The Best Book list accolades continue to come for Adam Begley’s biography, Updike. Click on the titles to access the full articles:

Mail Online

William Boyd picked Updike as “My Book of the Year”: “It’s curious how one can love a contemporary writer, read pretty much the entire oeuvre, yet remain almost wholly ignorant about the author’s life. John Updike was the case in point for me. I started reading him in my teens and carried on until his death in 2009. But this year brought Updike by Adam Begley (Harper £25) to fill the gap in my knowledge. It’s a wonderful, wise biography, judicious and intimately revealing, and does full justice to the highly complex individual that was Updike.”

stevereads: what I read and why

This blogger, no fan of Updike, nonetheless named Updike #3 on his list of Best Books of 2014: Biography: “Our monster-roundup, nearing completion, now advances far enough to include the milquetoast version that is lousy and forgotten 20th-Century novelist John Updike, the subject of this smart, sensitive, utterly fantastic biography by Adam Begley, who re-reads all of Updike’s novels even though they aren’t worth reading, re-lives all of Updike’s failed relationships even though not one single one of them reflects well on the ‘Rabbit, Regurgitated’ author, and sifts through all of Updike’s whining, minatory correspondence. It’s a protracted, masterful examination, a hefty and elegant tombstone with which to bury forever a worthless career.

WordsnQuotes

Another blogger ranked Updike “tied with Naomi Wood’s Mrs. Hemingway at #11″: “An illuminating biography, Updike beautifully unfolds John Updike’s difficult journey as a writer critically and creatively. If you are an Updike fin, this is the most thrilling experience since the first time you fell in love with Updike’s prose. Superbly intimate, Updike reads like a novel, Begley has a natural ease of swaying us into John Updike’s life and elevating the curiosity in one of the greatest American authors. Geeky looking in appearance and quiet Updike seems like a peculiar and boring subject to cover, but Begley implores us sot reevaluate the interest found in Updike’s life.

“John Updike himself was a work of fiction, every line he had written chronicles his progress as a human being. When critiquing a work of art, as W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley taught us, art and the artist must not be evaluated simultaneously; but as revealed by Begley, Updike’s mysterious charm lies in the latter reflection. Ailed by poverty and determined to never be a victim of it, Updike was a workaholic, sensitive, and internally a charmer with a killer wit. Most Updike readers will be surprised to discover that their beloved, private author drew direct inspiration from his experiences, although a true introvert, he confessed details of his life in his ornate prose. If you have read a couple of Updike novels, we recommend you dig a bit further, read more Updike and come back to this biography.”

brain pickings

On her blog, Maria Popova notes “The Best Biographies, Memoirs, and History Books of 2014” and gets to Updike at #15: “John Updike (March 18, 1932–January 27, 2009) wasn’t merely the recipient of two Pulitzer Prizes and a National Humanities medal, among a wealth of other awards. He had a mind that could ponder the origin of the universe, a heart that could eulogize a dog with such beautiful bittersweetness, and a spirit that could behold death without fear. He is also credited with making suburban sex sexy, which landed him on the cover of Timemagazine under the headline “The Adulterous Society” — something Adam Begley explores in the long-awaited biography Updike.

“Begley chronicles Updike’s escapades in Ipswich, Massachusetts, in the early 1960s, just as he was breaking through with The New Yorker — the bastion of high culture to which he had dreamed of contributing since the age of twelve. His literary career was beginning to gain momentum with the publication of Rabbit, Run in 1960 — the fictional story of a twenty-something suburban writer who, drowning in responsibilities to his young family, finds love outside of marriage. That fantasy would soon become a reality for 28-year-old Updike, a once-dorky kid who had gotten through Harvard by playing the class clown clad in his ill-fitted tweed jackets and unfashionably wide ties.

Dive deeper with the story of how Updike made suburban sex sexy.”

AbeBooks

There’s no text and no ranking, only a round-up of covers that link to places where you can buy the books, but Updike is also included in the bookseller network’s “Notable Non-Fiction Books of 2014.”

Roger Angell cites Updike in 2014 interview

Maybe inspired by all of the headlines the Cubs and other teams have been making with their big-splash off-season acquisitions, David Lull tracked down this interview with Roger Angell in which Angell mentions Updike’s famous tome on baseball and admits he modeled his own work after it.

“Annotation Tuesday! Roger Angell and the pitcher with a major-league case of the yips” was posted on March 11, 2014, and Angell’s comments about Updike come in response to the question, “Why baseball? What’s the pull for you?”

“Well, it was a good fit for me. I was always a baseball fan of good standing. I never planned to write this length; it was a huge surprise, an accumulating surprise. Shawn came to me in ’62, or something like that, and asked if I wanted to go down to spring training, because we hadn’t done enough sports. The only advice he gave me was, ‘There are two dangers in sportswriting: Toughness and sentimentality. Don’t be tough, and don’t be sentimental.’ And I said okay. The model for me going down there was John Updike’s Ted Williams piece, ‘Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,’ which had run a couple of years before. He put himself and his grownup sensibility into the stands. He was also a fan and an adulator of Ted Williams. It was probably Ted Williams’s last game. So he was writing about himself in the stands watching what happens, which is what I began doing in spring training. I was too nervous to sit in the press box, or to talk to any of the players — I didn’t dare do that. Spring training in those days was in Florida; a lot of very old, old people watching very young players. It was a nice mix. It was the first year the Mets were alive. They had not yet played a major league game. I saw them play the Yankees. That first year I wrote about the Mets a lot, because they were certainly a phenomenon. They were a terrible team that was loved by everyone in New York — antimatter to the Yankees. They were a terrible team but they were adorable. So I went back and wrote a little piece, which cranked me up and suggested I could do this.”

On Line opinion spotlights In the Beauty of the Lilies

On Line opinion, Australia’s e-journal of social and political debate, recently posted a critical article by Peter Sellick on John Updike’s In the Beauty of the Lilies.

On Line opinion, Australia’s e-journal of social and political debate, recently posted a critical article by Peter Sellick on John Updike’s In the Beauty of the Lilies.

“All the characters love the movies. Indeed Updike gives us a potted history of American movie making. It is obvious that the movies become, to a large extent, a window on reality and that in doing so they displace the key role of the Church of mediating reality. The narratives of Scripture are replaced by those of Bogart and Bacall,” Sellick writes.

“In Lilies Updike gives us a narrative of social, familial and spiritual decline that is associated with the loss of faith. In this he is no romantic, harking back to a lost and idealized Christendom. There has never been a time in which faith has not been fragile and rare. But he charts our time and finds ground to conclude that we are experiencing our very own crisis and that this is demonstrable by the isolation and foundering of the self of which Clark is the end product.”

“Updike gives us a narrative arc in Lilies that follows a family who had experienced a profound loss of faith, a professional churchman, considered, educated, comes to the conclusion that God does not exist. The effect of this event is worked out in the next three generations in detail. It is a convincing narrative. Like the gospels, it is a story that includes verifiable historical events and movements upon which a fictional overlay is placed. For me, the story resonates; I understand the connections that Updike makes. Such a narrative is able to cut through to the truth in a way that sociology finds difficult.”

Updike turns up on an Adult Swim animated series

John Updike was enough of a cultural presence that he was referenced in at least two episodes of “The Simpsons.” And now, five years after his death, his presence is still strong enough that the Pulitzer Prize-winning author turned up on a new animated Adult Swim series produced by Warner Bros.

In “The End,” Episode 1 from Season 1 of Mike Tyson Mysteries, an adult parody of the Scooby-Doo! mysteries, John Updike appears as a chupacabra attended to by a pigeon and contemplated by a centaur. “You can learn a lot” from his writing, the talking pigeon says. “Like sex.” To which the centaur responds, “Bird sex?”

Since Updike turns up dead, you could say it’s in bad taste. But that’s what Adult Swim series are all about. The complete episode can be viewed online on YouTube.

Blogger shares Updike postcard

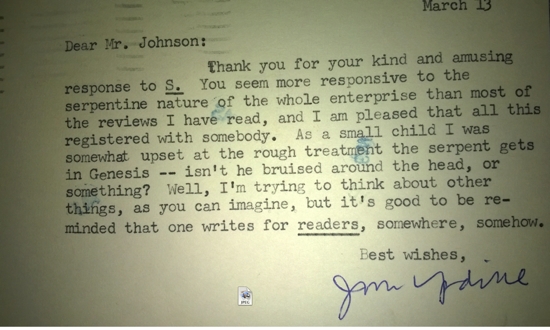

“Writing to Updike” is something that many readers and fans have done, and blogger Jeffrey Johnson has shared his own experience, complete with Updike’s response to his letter. Johnson notes Begley’s comment that Updike had mailed out “thousands of print-crowded three-by-five postcards” over his lifetime, and says, “Three of those thousands of postcards were addressed to me, one in response to each of three letters I wrote to Updike about his books.

“The first of those letters, written in the mid 80’s on my college electric typewriter, was a reflection on the novel Roger’s Version. The letter began with the thought that Updike might prefer that his readers would not bother to write back. The first line of the postcard sent from Updike–which landed in the general delivery box of the South Chatham Post Office and was handed across the counter to me–was, No, letters like yours written back are always welcome.

“A few years later, in response to comments I sent on his next novel S. which, like Roger’s Version, was an inspired reworking of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, Updike sent a note: