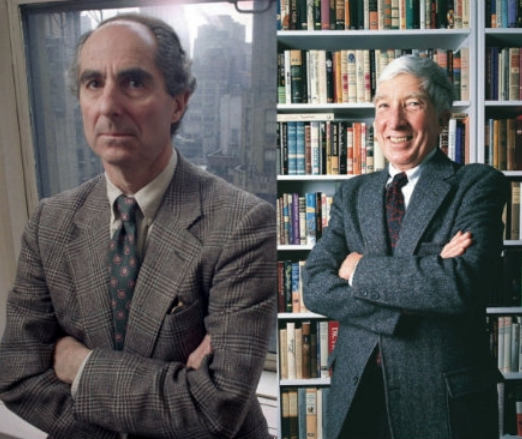

In his May 21, 2020 article on “The Philip Roth Archive,” Jesse Tisch described “A fan’s obsessive rummage through the letters and papers of the writer who died two years ago today” that “reveals a playful, funny, brilliant man.” The letters also reveal a great deal about the complicated relationship Roth had with fellow literary giant John Updike.

“Their relationship is hard to categorize, not a friendship, exactly, nor merely an acquaintance,” Tisch wrote. “For all their similarities—two literary grandees of the same generation, both precocious, prolific, obsessed with male desire and waning potency—they were strikingly different. Religious and secular. Serene and intense. High style and vernacular. Whereas Updike poured out novels, Roth, a plebeian laborer, assembled them brick by brick. To say that writing was pleasure for Updike and torture for Roth is to overstate things only slightly.

“The Roth-Updike letters reveal a deeper, more complex relationship than I had known about. Despite their differences, Roth admired Updike extravagantly, both as a novelist and a critic. “There’s no other writer (which is to say no one at all) in America whose high opinion means more to me than yours,” Roth wrote Updike in 1988. Roth pored over Updike’s reviews of his books, taking them to heart even when he didn’t agree: ‘take a look at page 181 of The Anatomy Lesson,’ he urged Updike in 1984. ‘My answer to the last paragraph of your review.’

“The Roth-Updike letters reveal a deeper, more complex relationship than I had known about. Despite their differences, Roth admired Updike extravagantly, both as a novelist and a critic. “There’s no other writer (which is to say no one at all) in America whose high opinion means more to me than yours,” Roth wrote Updike in 1988. Roth pored over Updike’s reviews of his books, taking them to heart even when he didn’t agree: ‘take a look at page 181 of The Anatomy Lesson,’ he urged Updike in 1984. ‘My answer to the last paragraph of your review.’

“Somehow, despite their mutual respect and occasional get-togethers, the friendship never deepened. Roth’s half of the correspondence is warm and funny (another difference: Roth was far funnier), his fondness tinged with envy. ‘Reading you when I’m at work discourages me terribly—that fucking fluency!’ Roth wrote Updike in 1978. That wasn’t the only source of envy. ‘He knows so much, about golf, about porn, about kids, about America,’ Roth told David Plante. ‘I don’t know anything about anything.’ Indeed, one picks up on a subtle antagonism to Roth’s joshing. ‘Poor Rabbit. Must he die just because you’re tired?’ he needled Updike in 1990. More than once, Roth bristled at Updike’s criticism. He couldn’t understand Jewish novels; he had no comprehension of Jewish history or the Jewish psyche. ‘We are in history up to our knees,’ he told an interviewer, dismissing Updike’s review of The Anatomy Lesson.

“To some degree, both men were guarded and self-protective. Updike’s shield was amiability; Roth’s was humor and flattery. Of the two, Roth seemed more eager to pursue a deeper friendship. Roth professed ‘affectionate sympathy and something even more than that’ to Updike in 1991, yet sensed a certain resistance, a studied aloofness, on Updike’s part. Any chance for friendship was ruined by Updike’s incisive criticism of Roth’s novels. Reviewing The Anatomy Lesson, Updike complained of ‘the grinding, whining paragraphs’ and suggested that ‘by the age of fifty a writer should have settled his old scores.’ That rankled. In 1993, Updike delivered several sharp blows to Roth’s ego in the process of criticizing Operation Shylock (final verdict: Roth was ‘an exhausting author to be with’). The final blow came in 1999, when Updike, writing in The New York Review of Books, endorsed Claire Bloom’s vindictive memoir of her relationship with Roth. That did it: Roth was furious; the men never spoke again. Late in life, his wounds somewhat healed, Roth would claim to regret their estrangement. ‘I think you are next after Gordimer,’ he wrote Updike in October 1991. Of course, neither would follow Gordimer, which proved another lasting connection between the men—America’s greatest nonwinners of the Nobel Prize.”

The fascinating article based on letters from the Philip Roth Archive covers a lot more ground than this. Here’s the link.