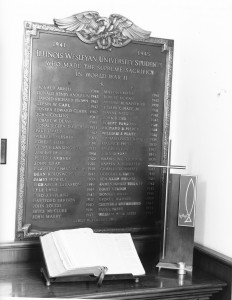

Ticket stubs from several of Awadagin’s performances

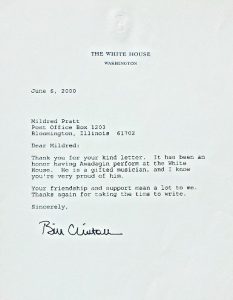

The Pratt family’s influence has been felt all over the world and the Tate Archives holds many interesting materials related to this influential family. Music aficionados will enjoy perusing through concert programs, performance schedules, ticket stubs, and other ephemera related to world-renowned concert pianist Awadagin Pratt, whose career has spanned four decades. Awadagin began piano lessons when he was six years old and entered the University of Illinois to continue those studies at the age of 16. Awadagin was the first student to receive diplomas from the Johns Hopkins University’s Peabody Conservatory of Music in three performance areas – piano, violin, and conducting. Appearing in People Magazine, Newsweek, and named one of the 50 Leaders of Tomorrow in Ebony’s 50th anniversary issue, he has performed in both of Presidents Clinton’s and Obama’s White Houses, and showcased his talents as a performer and conductor in concert halls and symphonies on several continents. Our collection of materials associated with Awadagin will keep any music lover busy for hours; but, that’s not all there is to this collection!

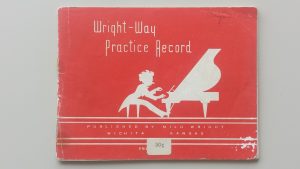

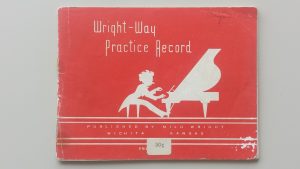

Awadagin’s piano lesson practice log

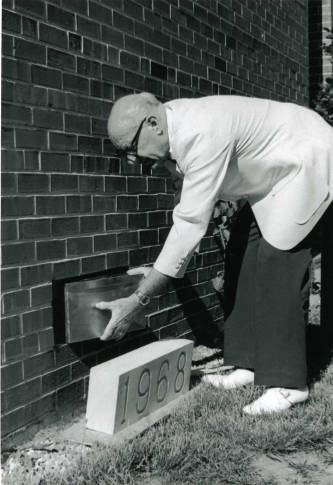

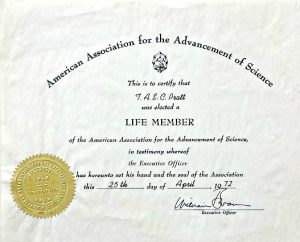

Awadagin’s father, Dr. T.A.E.C. “Ted” Pratt (1936 – 1996), mother, Dr. Mildred Sirls Pratt (1928-2012), and his sister, Dr. Menah Pratt-Clark are highly admired professionals in their respective fields as well. A music enthusiast in his own right, Ted was born in Sierra Leone, and raised in a family where his sisters were taught the piano, and he and his brothers learned to play the organ. Ted grew up receiving his education from some of the world’s finest institutions, including the Prince of Wales School and Fourah Bay College in Freetown, Sierra Leone; Durham University in Durham, England; and, the Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia. After receiving his M.S. in Physics from the Carnegie-Mellon Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, he became the first person from Sierra Leone to earn his PhD in Nuclear Physics, also from the Carnegie-Mellon Institute. The Pratt Family Collection contains many of Ted’s published articles, research, teaching materials, family letters and personal ephemera from every period of his life.

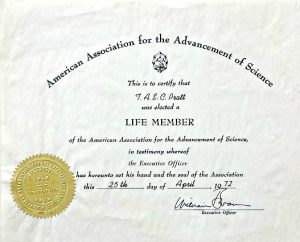

Dr. Theodore Pratt’s lifetime membership award to the American Association for the Advancement of Science

As Professor of Sociology & Anthropology at Illinois State University, and co-founder and co-director of the Bloomington-Normal Black History Project, Dr. Mildred Pratt has been widely recognized for her dedication to making our local community a welcoming place for people of all backgrounds. She is a recipient of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity’s Citizen of the Year Award in 1987, as well as, the Town of Normal’s Human Relations Reward in 1989. After the death of her husband, Mildred founded the Pratt Music Foundation in honor of his love for classical music. The Foundation provides financial assistance to students in grades 2-12 pursuing instruction in piano or strings. Donations to the Foundation can be made at: The Pratt Music Foundation, c/o Illinois Wesleyan University, PO Box 2900, Bloomington, IL 61702.

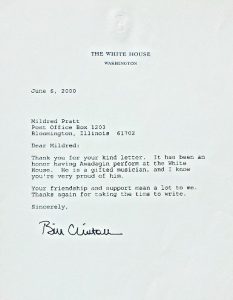

Letter received from President Blill Clinton in 2000

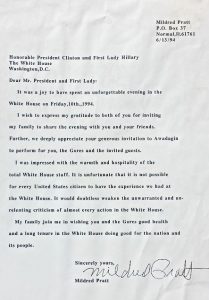

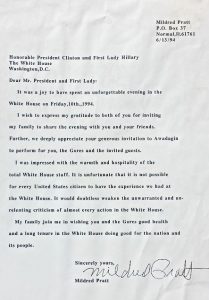

Letter written by Dr. Mildred Pratt to President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton in 1994

Dr. Menah Pratt-Clark, Awadagin’s sister, followed her parents’ footsteps into the world of academia. She holds a B.A. and M.A. in Literary Studies from the University of Iowa, as well as, a M.A. and PhD. in Sociology from Vanderbilt University, and, is currently serving as the Vice Provost for Inclusion and Diversity and Vice President for Strategic Affairs at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Prior to her most recent position with Virginia Tech, she has served as a university compliance officer at Vanderbilt University, and Associate Chancellor for Strategic Affairs at the University of Illinois, a position she held for ten years. Menah is also author of the book, Critical Race, Feminism, and Education: A Social Justice Model.

If you would like to learn more about the Pratt family, please visit the Tate Archives and Special Collections on the 4th floor of IWU’s Ames Library!