Guest posted by Melissa Mariotti

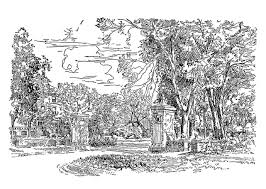

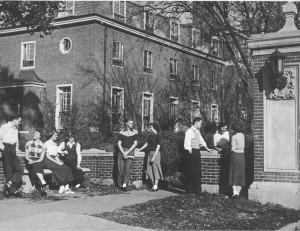

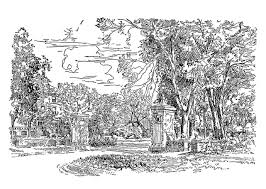

IWU West Gate. Photo copied from IWU Website.

As most students and faculty know, there are several main entrances into Wesleyan’s campuses. There is the North entrance on Franklin Avenue, the South entrance by Empire Street, the East entrance by Park Street, and the West entrance by Main Street. There is not much known about the latter entrance. It stands between Pfieffer and Gulick Halls and bears the inscription:

“We stand in a position of incalculable responsibility to the great wave of population overspreading the valley of the Mississippi. Destiny seems to point out this valley as the depository of great heart of the Nation. From this center mighty pulsations, for good or evil, must in future flow, which shall not only affect the fortunes of the Republic but reach in their influence other and distant Nations of the earth.”

The West Gates, looking north toward the Women’s Dormitory. From a 1931 booklet of pen sketches of Illinois Wesleyan University; RG 4-16/2/4.

Upon further research, it was discovered that the gates were ”erected and presented to the school by the Bloomington Association of Commerce in 1921” (Founders’ Day Convocation, 1999). There are two differing theories about where this quote came from. According to the 1960 Wesleyana, it is “an excerpt from the report on education to the annual meeting of the Illinois Conference held in Springfield in 1854.” But according to an Argus article from February 13th, 1940, it was said on December 18th, 1850 from the “Conference Record.”

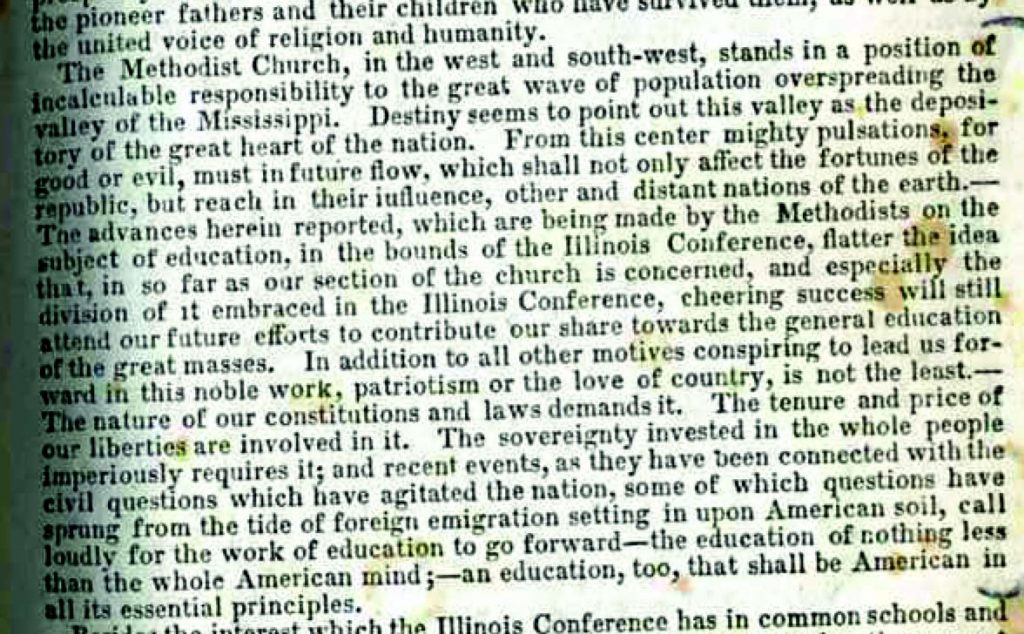

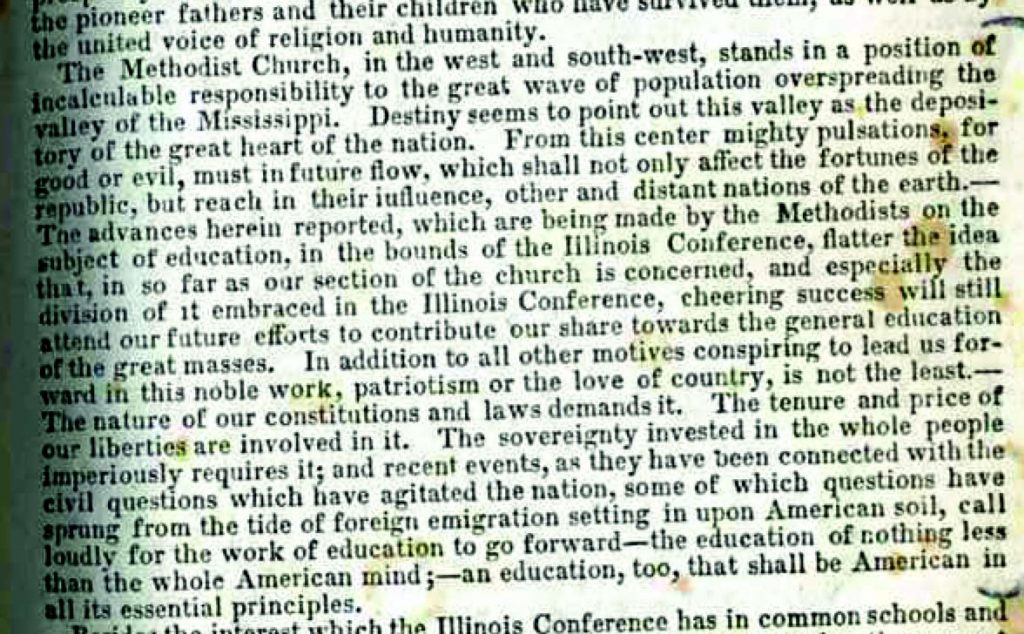

The quote (see image below) was verified in the Methodist Conference Record of 1854 by the archives that holds the Conference Record for 1854: The Illinois Great Rivers Conference Archives at MacMurray College, Jacksonville, Illinois. There is more to the quote than was summarized on our West Gates, but the spirit of the passage resonates just as much today as it did for our Founders.

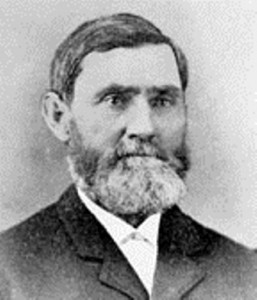

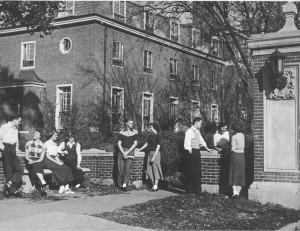

Students around the West Gate in 1951. From the 1951 Wesleyana.

The quote that is inscribed on the gate is said to represent “the ‘incalculable responsibility’ the founders of Illinois Wesleyan felt in the work they had undertaken” in establishing Illinois Wesleyan as an “institution of learning” (President Wilson, Founder’s Day Convocation Remarks, 2006). It describes the passion that the Founders had for teaching and learning, along with the many obstacles they had to face into creating the school. This inscription is referenced many times during Founders’ Day Convocations, and is evident in the care and consideration of all who work to sustain and advance that goal today.

Education Committee Report, 1854 Central Illinois Conference Journal

The text is as follows: “The Methodist Church, in the West and Southwest, stands in a position of incalculable responsibility to the great wave of population overspreading the valley of the Mississippi. Destiny seems to point out this valley as the depository of the great heart of the nation. From this center mighty pulsations, for good or evil, must in future flow, which shall not only affect the fortunes of the republic, but reach in their influence, other and distant nations of the earth. The advances herein reported which are being made by the Methodists on the subject of education in the bounds of the Illinois Conference, flatter the idea that, in so far as our section of the church is concerned and especially the division of it embraced in the Illinois Conference, cheering success will attend our future efforts to contribute our share towards the general education of the great masses. In addition to all other motives conspiring to lead us forward in this noble work, patriotism or the love of country is not the least. The nature of our constitutions and laws demands it. The tenure and price of our liberties are involved in it. The sovereignty invested in the whole people imperiously requires it; and recent events, as they have been connected with the civil questions which have agitated the nation, some of which questions have sprung from the tide of foreign emigration setting in upon American soil, call loudly for the work of education to go forward-the education of nothing less than the whole American mind; an education, too, that shall be American in all its essential principles.”