![2016-05-10_00.50.24[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.50.241-300x239.jpg)

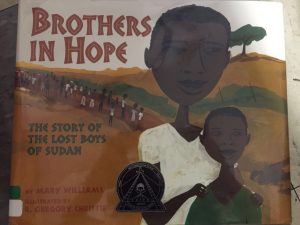

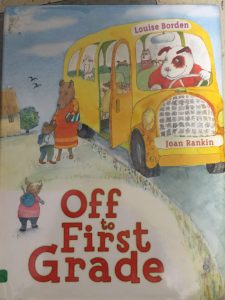

Author: Alice Walker

Illustrator: Stefano Vitale

Publisher/Year: Harper Collins, 2007

Pages: 28

Genre: Poetry

Analysis:![2016-05-10_00.49.13[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.49.131-300x264.jpg)

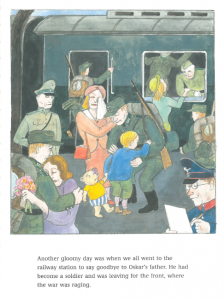

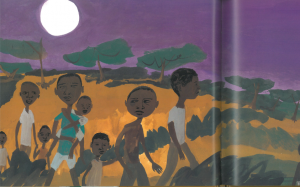

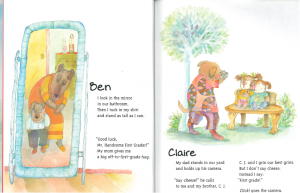

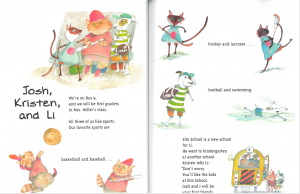

Without referring to any war in particular, Alice Walker in Why War is Never a Good Idea, poetically personifies war and its devastation. Walker depicts war as an unpredictable, out-of-control, blind, bad-mannered, gluttonous, and unwise force of man that is inconsiderate of the destruction it wreaks on innocent victims.

Walker’s book certainly functions as a mirror for readers, especially children who have immigrated to the United States in search of safety and security, or felt firsthand the devastation of war (e.g. through death of a loved one, or flattening of one’s hometown). In addition, Walker’s poem introduces readers who have never felt the impacts of war to war’s many unknowing victims: a boy and his donkey, nursing mothers, ancient artifacts, pumas and parakeets, and civilians who are left to die from contaminated water. Walker’s picture book also calls readers, young and old, to not blindly support a tradition or concept (war) simply because it is old. For, as Walker comments: “Though War is Old / it has not become wise,” carrying with it a bundle of unforeseen consequences and striking at a moment’s glance (p. 16).

Power rests in the personified hands of War, who acts without thinking, attacks without warning, and consumes without asking. The victims, both human and inanimate, are the unfortunate recipients of war’s havoc. Why War is Never a Good Idea shows lower-class native people (Asian, Hispanic, and African American) and their culture to be destroyed by war. While accurate, this depiction does not fully represent war’s devastation. Only on the final page of the book does a white family of three appear as a victim, individuals who will also have to drink the contaminated water. Non-White soldiers are not the only ones exploited by the war.

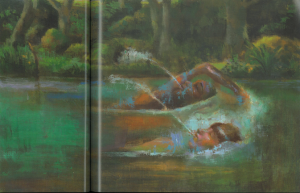

The text communicates the differences between what war is and is not, highlighting how unforeseen consequences lie in this difference. The text also emphasizes the innocence of what war destroys, be it a boy dreaming of polenta and eggs for dinner, or a mother singing a lullaby to her baby. Weapons of war and destruction are illustrated realistically (compared to cartoon drawings) and described rather elusively. The photographs interact with hand drawn landscapes for a dramatic effect (e.g. wheel of truck ripping through the paper on which the village is drawn; little green soldier figurines sucked into a wave of grimy, contaminated water…). Images magnify how from all different angles—taste, smell, sight, and touch—war is bad and futile. Images also elaborate on the cruelty of war. All of the pre-war images of villages and natives are illustrated with a rainbow of bright colors to show their momentary peace and freedom. The colors turn more eerie and burnt as destruction ensues. Why War is Never a Good Idea promotes a global anti-war attitude, criticizes the unlimited power of war, and raises ethical concerns regarding the effects of war on victims.

![2016-05-10_00.46.11[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.46.111-254x300.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.44.45[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.44.451-300x188.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.42.10[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.42.101-300x223.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.41.15[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.41.151-300x220.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.48.04[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.48.041-300x266.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.39.24[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.39.241-300x143.jpg)