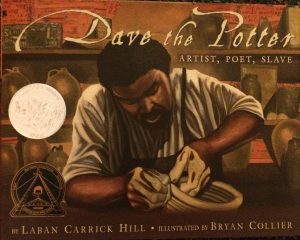

Author: Laban Carrick Hill

Illustrator: Bryan Collier

Publisher and Year: Little, Brown and Company, 2010 (Caldecott honor, Coretta Scott King Award)

Number of Pages: 40 Pages

Genre: Historical Fiction

Dave the Potter tells of Dave, who was a slave in the 1800s in South Carolina (Hill, 2010). He was a very skilled potter while also being a poet. This story honors the craftsmanship of Dave’s pottery along with his poetry.

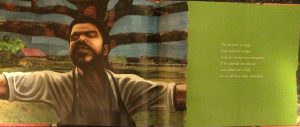

This story serves as a window into the life of Dave as a slave and as a craftsman. However, this book only focuses on Dave’s pottery and some poetry, but does not tell of his struggles as a slave. In addition, the last three pages of the book highlight some of Dave’s poetic verses while explaining historical facts about him. This book seems to portray Dave as enjoying being a slave in the South. For example, the images show Dave with facial expressions of content and serenity as if he enjoys the current position of being a slave doing his work. As a mirror, it reflects the African American culture and honors a man of color that brought beauty to pottery and poems. As with Dave being a slave, he did not have power. He is portrayed as just going about the day while creating large pots. Yet, the end of the book includes an author and illustrator’s note. Both explicitly state the extensive research they did on Dave (it is all cited in the book), and even visited the place where he was a slave. Though the way Dave was depicted was not exactly accurate (he lost a leg but is drawn with two legs), the author and illustrator made it very clear that though Dave was a slave, the purpose of this book was to honor his craft of pottery and poetry. This story represents the African American culture by honoring a man of color. As the author and illustrator made known, they wanted to represent Dave for his skills as a potter and poet. They portray him as a figure worthy of being remembered as a man of color in history. At the same time, this breaks any stereotype that showed slaves having no creative skills because Dave was able to create beautiful verses of poetry and pottery as a man of color.

Perceptually, the book is a Caldecott honor meaning that the artwork is important to the emotion of the story. In addition, image is on one page while text on another to allow the reader to focus on both text and image. The text is on a solid colored background showing it is to be noticed by the reader. Dave is portrayed as very calm, quiet, and comfortable in work. My criticism of this is that with him being a slave, I think this book portrayed him to be more comfortable with his life as a slave than he actually was. Structurally, there are three pages of Dave’s historical background included at end of book showing that the author and illustrator want to share the story of Dave’s pottery and poetry. In addition, they include citation page and author and illustrator’s note. This shows credibility to where they found their information about Dave’s story while also explaining why they chose to focus on his craftsmanship and poetry. The text and images don’t mirror one another but still need both to gain full experience from book. Also, no framing of the images allows the audience to come into Dave’s story. Overall, this book honors a man with tremendous skill even with its questionable depictions of his life. As a theme from the book, the author and illustrator highlight that the fine arts bring beauty to the world.

![2016-05-13_14.06.41[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-13_14.06.411-300x258.jpg)

![2016-05-13_14.05.50[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-13_14.05.501-300x139.jpg)

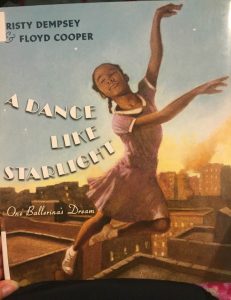

![2016-05-10_00.46.11[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.46.111-254x300.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.44.45[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.44.451-300x188.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.48.04[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.48.041-300x266.jpg)

![2016-05-10_00.39.24[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-10_00.39.241-300x143.jpg)