![2016-05-27_11.37.41[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-27_11.37.411-234x300.jpg)

Author: Kevin Henkes

Illustrator: Kevin Henkes

Publisher/Year: Greenwillow Books, 2015

Pages: 29

Genre: Fiction

Analysis:

Waiting is the curious story of five toys who live on a window ledge. Four of the toys (the owl, puppy, bear, and pig) wait for something specific (e.g. moon, snow, wind, rain, respectively), but the rabbit simply enjoys looking out the window and waiting. Told and drawn from the perspective of the toys, Waiting explores their life, from sleeping and new ledge-mates to the wonderful and scary things they observe through the window.![2016-05-27_11.38.16[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-27_11.38.161-212x300.jpg)

Waiting can be seen as a metaphor for life; readers can relate to one, some, or all of the toys and their experiences. Each toy is waiting for something different, but they nonetheless wait together as a sort of community. From this, children can see that every person has a unique source of happiness. For example, the pig waits for rain because she has an umbrella, while the bear waits for wind so his kite can fly. Children who have yet to discover their preferences and interests can relate to the rabbit, for he finds happiness in simply looking out the window, waiting for nothing in particular. Children can also see their lives portrayed in other experiences of the toys as well. The five toys are a dynamic community; the way some toys go away to return later on (after being played with) or the introduction of new toys to the ledge, resembles how people in our own lives come and go, sometimes returning and other times not. Waiting can indirectly function as a door because the original five toys model conviviality. Although the five toys were initially surprised when a cat with patches joins them on the ledge, they welcome the cat and patiently wait to see what it is waiting for (kittens/four nesting cats). At the end of the book, all ten animals happily wait together and intermingled.

Power is distributed evenly in Waiting. The family of five, and later ten, animals are drawn and described to be equals. They welcome each other and coexist. It can, however, be assumed that power rests with the child owner of the toys who, although not pictured or mentioned, is responsible for removing, replacing, and breaking some toys on the shelf. Without the supposed presence of their owner, the toys would not be waiting for wonderful things to happen. Culture does not really figure into Henkes’ Waiting. Without seeing the toys’ owner, the set of toys could belong to a child of any race, gender, or even social class.

The text in Waiting communicates how each animal’s life and happiness on the ledge is defined by waiting for something. Besides the occasional new animal or visitor, all the animals truly have is themselves and the window for entertainment; their lives, like the text itself, is rather plain until what they are waiting for arrives. As much of the text is vague and told from the perspective of toys, the illustrations both mirror and add to the text. Images add a curious and playful feeling. The changing expressions (e.g. surprise, questioning, peace, joy, and fright) and body language of the toys in response to new can tell the story by itself. The fact that the animals are waiting by a window is both symbolic and a little ironic; windows are said to represent thresholds, progress, and growth, yet by spending most of their days waiting, the animals really are not moving forward, and their happiness is not always assured. The animals are often shown peering up and through the window to emphasize how the happenings outside of their window offer a picturesque, dream-like quality (i.e. fluffy white snow, rainbows). Finally, by having the animals’ backs to the reader in the illustrations, readers are invited to peer through the window as well. Waiting embodies themes of the inclusion and acceptance of others, and shows patience to be a virtue.

![IMG_9670 [2578141]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/IMG_9670-2578141-218x300.jpg)

![IMG_9671 [2578142]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/IMG_9671-2578142-188x300.jpg) When an unwanted ghost boy, Leo, is “evicted” from his ghost home, he is forced to live on the streets. It isn’t until he meets a young, believing girl that he finally feels accepted and seen.

When an unwanted ghost boy, Leo, is “evicted” from his ghost home, he is forced to live on the streets. It isn’t until he meets a young, believing girl that he finally feels accepted and seen.

![2016-05-27_11.37.41[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-27_11.37.411-234x300.jpg)

![2016-05-27_11.38.16[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-27_11.38.161-212x300.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.18.00[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.18.001-298x300.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.16.43[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.16.431-300x168.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.19.14[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.19.141-300x233.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.32.01[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.32.011-300x116.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.21.03[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.21.031-286x300.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.20.22[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.20.221-300x159.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.22.46[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.22.461-219x300.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.21.53[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.21.531-300x214.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.28.25[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.28.251-300x298.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.29.33[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.29.331-300x160.jpg)

![2016-05-16_16.27.04[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-16_16.27.041-241x300.jpg)

![2016-05-27_11.03.56[1]](https://blogs.iwu.edu/lrbmt2016/files/2016/05/2016-05-27_11.03.561-300x198.jpg)

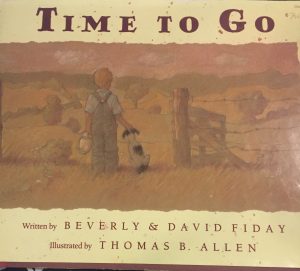

Author(s): Beverly and David Fiday

Author(s): Beverly and David Fiday