What started at the turn of the century as an effort to gain a day of recognition for the significant contributions the first Americans made to the establishment and growth of the United States, has resulted in a whole month being designated for that purpose. On August 3, 1990 U.S. President George H. W. Bush declared the month of November as National American Indian Heritage Month, thereafter commonly referred to as Native American Heritage Month. First sponsorship of “American Indian Heritage Month” was through the American Indian Heritage Foundation by the founder Pale Moon Rose, of Cherokee-Seneca descent and an adopted Ojibwa, whose Indian name Win-yan-sa-han-wi “Princess of the Pale Moon” was given to her by Alfred Michael “Chief” Venne.

This commemorative month aims to provide a platform for Native people in the U.S. to share their culture, traditions, music, crafts, dance, and ways and concepts of life. This gives Native people the opportunity to express to their community, both city, county and state officials their concerns and solutions for building bridges of understanding and friendship in their local area.

This month, Theme Thursdays will focus on revolutions within and related to Native Americans with our first post highlighting Native Americans’ roles in environmentalism and environmental justice.

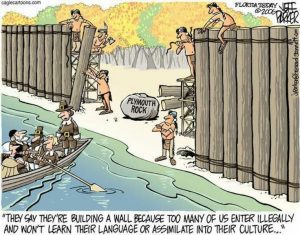

The environmental revolution has been years in the making; contrary to stereotypes, Native American Indians do not have a “natural” affinity with environmentalism. What they do have is lands with a long history of being the dumping ground for uranium tailings, nuclear waste, and toxic chemicals. Reviving traditional land-based spiritual/cultural practices, and inventing new ones for the 21st century, play an increasingly vital part of many reservation cultures threatened by environmental pollution and cultural genocide.

Efforts at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline are just one example among many of Native Americans fighting for environmental rights. This video, available through Kanopy, documents the largest river restoration project in American history. Nearly three hundred miles in length, flowing from southern Oregon to northern California, the vast communities of the Klamath River have been feuding over its water for generations, and as a result, bad blood has polluted their river and their relationships equally. The film examines the complicated history of this conflict: how anger, fear and distrust have undermined the Klamath’s communities for decades.

This video, also available through Kanopy, chronicles the efforts of several tribes as they fight to end the harmful use of coal and work to bring clean, renewable energy projects into their communities, including wind and solar power. As Power Paths reveals, many Native American tribes are not waiting for the government to act. Instead, they are actively seeking investors and a way to control their own energy and sell the rest to the power companies.

This video, also available through Kanopy, chronicles the efforts of several tribes as they fight to end the harmful use of coal and work to bring clean, renewable energy projects into their communities, including wind and solar power. As Power Paths reveals, many Native American tribes are not waiting for the government to act. Instead, they are actively seeking investors and a way to control their own energy and sell the rest to the power companies.

Native Americans and the environment: Perspectives on the ecological Indian, edited and with an introduction by Michael E. Harkin and David Rich Lewis; foreword by Judith Antell; preface by Brian Hosmer; afterword by Shepard Krech III

American Indian environments: Ecological issues in Native American history, with contributions from Kai T. Erikson … [et al.]; edited by Christopher T. Vecsey and Robert W. Venables

American environmentalism: Readings in conservation history, edited by Roderick Frazier Nash

On the flip side, some Native American traditions stand in contrast to federal regulations. The idea that tribes have an inherent right to govern themselves is at the foundation of their constitutional status – the power is not delegated by congressional acts. Congress can, however, limit tribal sovereignty. Unless a treaty or federal statute removes a power, however, the tribe is assumed to possess it. Current federal policy in the United States recognizes this sovereignty and stresses the government-to-government relations between Washington, D.C. and the American Indian tribes. However, most land is held in trust by the United States, and federal law still regulates the political and economic rights of tribal governments.

One prime example of Native customs conflicting with federal regulations is whale hunting. In 2015, the Washington state native Makah Tribe has asked the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to waive federal marine mammal protections that ban the hunt. The Makah historically hunted gray whales for food and spiritual ceremonies but ceased in the 1920s, when gray whale numbers were at an all-time low. Learn about another whale-hunting tribe, the Inuit, in this e-book, available through Ames.