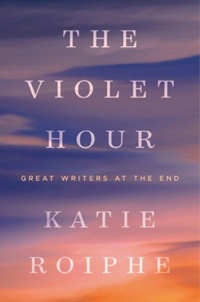

Katie Roiphe included John Updike in her book The Violet Hour, so it’s no surprise that a review of that book would cite Updike, as Shirley Hershey Showalter did for The Christian Century. In “Death’s call and our response,” published October 2, 2016, she writes,

Katie Roiphe included John Updike in her book The Violet Hour, so it’s no surprise that a review of that book would cite Updike, as Shirley Hershey Showalter did for The Christian Century. In “Death’s call and our response,” published October 2, 2016, she writes,

“Kalanithi uses a quotation from Montaigne as an epilogue: ‘If I were a writer of books, I would compile a register, with a comment, of the various deaths of men: he who should teach men to die would at the same time teach them to live.’ The quotation could apply to Katie Roiphe’s book also. The Violet Hour takes up Montaigne’s challenge but with less confidence in the outcome. Roiphe roiled cultural waters in the 1990s withThe Morning After: Sex, Fear, and Feminism. The Violet Hour defies genre, mixing memoir, journalism, biography, and literary criticism as it ponders the dying of six writers—Sigmund Freud, John Updike, Dylan Thomas, Maurice Sendak, James Salter, and Susan Sontag.”

Later, she writes, “Updike is the only practicing Christian in the group. His lifelong devotion to the Book of Common Prayer and the Episcopal Church present a puzzle to Roiphe. She’s not tripped up by the apparent contradiction of his adulteries; she has a special interest in his linking of adultery and immortality: ‘I have a soft spot for those who try to defeat death with sex.’ It’s irony, not sex, that makes it difficult for her to understand Updike’s religious life.

“She explains in an endnote that Updike’s biographer Adam Begley helped her see continuity where she could only see confusion. Updike’s final book of poems, Endpoints, includes these lines about clergymen: ‘comical purveyors / of what makes sense to just the terrified.’ Roiphe settles on this explanation: ‘Updike approached everything under the sun with irony, including his deeper passions, his beliefs, his sources of marvel and awe.'”

Here’s the full article.

John Updike Society cofounder and former director Jack De Bellis, whose John Updike Encyclopedia and John Updike’s Early Years have been indispensable for Updike scholars, was featured in an interview on WDIY, Lehigh Valley’s Community NPR Station, on Dec. 6, 2016.

John Updike Society cofounder and former director Jack De Bellis, whose John Updike Encyclopedia and John Updike’s Early Years have been indispensable for Updike scholars, was featured in an interview on WDIY, Lehigh Valley’s Community NPR Station, on Dec. 6, 2016.