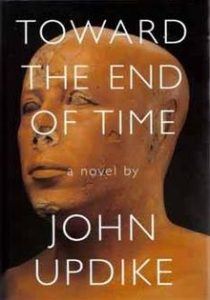

On Feb. 1, 2026, Martin Wenglinsky, an Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Quinnipiac University, posted on his blog the first of his two-part examination of John Updike’s futuristic novel, Toward the End of Time, which he called a “deficient” or “deformed” epic.

“Let me explain,” Wenglinsky wrote. “An epic is a story of war and family and a journey and one or more heroic protagonists and what might be endlessly elaborated episodes that convey some deep meaning about human nature, while novels, which are another kind of deformed epics, have protagonists whose histories are never retold but made up and just trying to manage life.”

In Toward the End of Time, Wenglinsky wrote, “The war envisioned is a limited exchange of atomic weapons between China and the United States that takes place a few decades in the future of the time the novel was published. The people in the novel are civilians trying to cope with the aftermath, which makes sense because the war that engulfed the world in the second half of the twentieth century was the Cold War, which had hot skirmishes in Korea and Vietnam and the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan, but unlike in other wars mostly in prospect, a full out exchange never happening even if many predicted it, imaginations filled with the nuclear apocalypse just thirty minutes away from total mutual destruction. So this war is a science fiction war, and Updike’s innovation is that there is a limited exchange so that the United States has had severe but not total annihilation, which is different from apocalyptic science fiction projections as happens in Shute’s On the Beach (1957), or Christopher’s No Blade of Glass (1956) or Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951) or to my mind the most scary documentary style BBC production, Mick Jackson’s Threads (1984)) which showed the reduction of England to a medieval economy and society. Rather, the United States, in Updike’s imagination, remains organized even if diminished and it is unclear whether it will recover or fall into anarchy.

In Toward the End of Time, Wenglinsky wrote, “The war envisioned is a limited exchange of atomic weapons between China and the United States that takes place a few decades in the future of the time the novel was published. The people in the novel are civilians trying to cope with the aftermath, which makes sense because the war that engulfed the world in the second half of the twentieth century was the Cold War, which had hot skirmishes in Korea and Vietnam and the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan, but unlike in other wars mostly in prospect, a full out exchange never happening even if many predicted it, imaginations filled with the nuclear apocalypse just thirty minutes away from total mutual destruction. So this war is a science fiction war, and Updike’s innovation is that there is a limited exchange so that the United States has had severe but not total annihilation, which is different from apocalyptic science fiction projections as happens in Shute’s On the Beach (1957), or Christopher’s No Blade of Glass (1956) or Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951) or to my mind the most scary documentary style BBC production, Mick Jackson’s Threads (1984)) which showed the reduction of England to a medieval economy and society. Rather, the United States, in Updike’s imagination, remains organized even if diminished and it is unclear whether it will recover or fall into anarchy.

“Updike’s novel is no reduction of a society into Hobbesian anarchy. Seafood is shipped from the East Coast to the decimated Midwest. Commerce also continues in that protection rackets spring up and young women openly advertise their personal services in the major newspapers and a local scrip has replaced the United States dollar but there are still country clubs and Federal Express and mail service and a diminished food market in some stands around downtown Boston. What Updike retains from the apocalyptic genre, which is only somewhere in the epic mode, as is the case with “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (c. 1400), which is full of foreboding about what will be the fatal mistake of the hero, is a sense of dread and despair: that something even worse will happen and that the eventual fate cannot be avoided however people battle on to restore what was once normal life. Achieving that tone in a less than complete apocalypse is a considerable achievement for Updike.

“But there is much more going on than that,” Wenglinsky wrote.

Read Part 1 of his essay, “John Updike: Toward the End of Time“