We have stumbled across a new critical essay (emphasis on the critical)—“Nights of the Lepus: Circling around and with Rabbit, Run by John Updike”—by Alberta University of the Arts professor Christopher Willard. It begins,

“In an early review of Rabbit, Run David Boroff of The New York Times wrote, “The author’s style is particularly impressive; artful and supple, its brilliance is belied by its relaxed rhythms. Mr. Updike has a knack of tilting his observations just a little, so that even a commonplace phrase catches the light. The prose is that rarest of achievements—perfectly pitched voice for the subject” (Boroff, 1960). But Updike’s noticing and skewing of details is by far less than the whole of his novel, although this is the aspect upon which many critics dwell. Updike can recognizably follow Emily Dickinson’s advice to “tell it slant” but just as frequently his relaxed rhythms and details are neither here—furthering the story along with necessary thoughts by Rabbit, nor there—lapsing into a full stream of consciousness carried by linguistic brilliance as found for example in Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet.

“The tension inherent in allowing passages to hover in a middle space without commitment to one or the other intent is at times frustrating but that said, Updike deserves praise for a masterwork in free indirect discourse of which in my view we can never have enough examples. Then again, flip side, at his blandest, Updike comes off like the Alex Katz of writing, the darling of those who prefer style like warm Cheez Whiz so it oozes down their throats without too much conscious swallowing.”

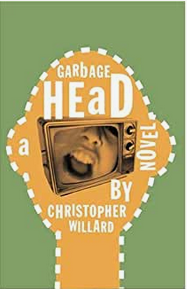

Clearly not a fan, Willard, who was born in Maine and has written several works of fiction himself, concludes,

“Elevating the mundane is an art, Robbe-Grillet comes to mind or Céline, and then a whole host of stream of consciousness novels flow into this river. Updike never went to these places in Rabbit, Run. When his writing tends toward a stream of consciousness, he engages the damper. When the writing starts getting too internal he brings it back to the detail. He never wants, it seems, to let the writing take him where it might or must take him, instead he continually forces it back to the method, and it’s a strong method, although his reliance on it could earn him the nickname ‘The Stephen King of a Great Literary Modernism.’ I think too of the band Boston, with a groundbreaking first album and a remainder of an oeuvre comprised of pastiche, or of Jackson Pollock who ended up doing parodies of Pollocks where the flame of unadulterated engagement between one’s soul and the world seems cast off for method and form.”

A few examples to back up the claims would have been nice.