Cancer Today, the publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, featured “A Storied Life” by writer Sue Rochman in the Winter 2015-16 issue, which is also available online. In it, Rochman details how “literary realist John Updike used the scaffold of his own life, including his lung cancer diagnosis, to explore the shared experiences of our time.”

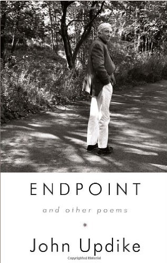

She writes, “Not only did he write in many forms, Updike wrote all the time, producing on average a book a year. That didn’t change after he was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2008. He spent the months before he died writing poems on facing mortality, many of which were published in his collection Endpoint and Other Poems.”

She writes, “Not only did he write in many forms, Updike wrote all the time, producing on average a book a year. That didn’t change after he was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2008. He spent the months before he died writing poems on facing mortality, many of which were published in his collection Endpoint and Other Poems.”

Lung cancer, Rochman reports, “is divided into two main types: small cell, which makes up about 15 percent of all diagnoses and non-small cell, which accounts for about 85 percent.

“It’s not widely known what type of lung cancer Updike had. It is known that he began to have some breathing problems in the summer of 2008. The initial diagnosis was bronchitis. When the cough didn’t clear, he was told it was pneumonia, a diagnosis he described as ‘oblong ghosts, one paler than the other on the doctor’s viewing screen’ in a poem dated Nov. 6. Two weeks later, as Thanksgiving approached, Updike spent five days at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, undergoing the tests that led to his lung cancer diagnosis.

“A misdiagnosis of pneumonia is ‘unfortunately, a common scenario,’ says medical oncologist Joan Schiller, deputy director of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. ‘Pneumonia is a heck of a lot more common than lung cancer, so it’s understandable that someone with a cough would be treated for pneumonia and then later find out it is lung cancer.’

“When people die so quickly from cancer, it is often assumed the disease spread quickly. That can and does happen, but another common reason for a late lung cancer diagnosis is that it can be hard to know it’s there. ‘One reason is that the lungs don’t have a lot of nerves, so it doesn’t cause pain—and you can’t see it,’ says Schiller. Still, she says, even for lung cancer, Updike’s two-month span from diagnosis to death was unusually quick.

“Updike’s cancer was treated with chemotherapy. Were he diagnosed today, says Gregory A. Masters, a medical oncologist specializing in lung cancer at Christiana Care’s Helen F. Graham Cancer Center in Newark, Delaware, he might have had more options.

“‘Instead of having everyone with stage IV lung cancer get the same chemotherapy,’ says Masters, ‘we now see if the patient has one or more of the specific gene alterations that allow us to use a targeted therapy. If they do, we can give them a treatment that is more effective, less toxic and that will control the tumor for more time.'”

Here’s the complete article, which also offers a career summary of Updike and his literary importance.

If you shop Amazon.com, you can help the John Updike Society by changing your bookmark from amazon.com to smile.amazon.com so that all orders go through the “smile” url. Amazon will donate .5 percent of eligible purchases directly to the Society.

If you shop Amazon.com, you can help the John Updike Society by changing your bookmark from amazon.com to smile.amazon.com so that all orders go through the “smile” url. Amazon will donate .5 percent of eligible purchases directly to the Society.