Reminiscences 2025

Another add-on trip with David went in 2006 to another of the ancient capitals of China—Kaifeng. That trip was enlightening, too. As I looked at what was happening in China, I realized that China was improving infrastructure and rebuilding historical sites. Unlike the Cultural Revolution, when only an impassioned intervention from Zhou En-lai saved the Forbidden City, the Chinese were burnishing places like the palace at Kaifeng. In Kaifeng, for example, David and I went to the sites commemorating the Jewish Community in Kaifeng—yes, along the Silk Road, Jewish and Muslim merchants plied their trade. The site of the old synagogue had been replaced by a church; that church, in turn, was the early 20th century home of a Canadian Bishop, who was also a collector. Remnants of the Muslim/Jewish period are in the Royal Ontario Museum.

Hello from Luoyang

May 25. 2006

The last 24 hours were frantic, but as JR can tell you, traveling with two people is a lot different than with 29!

The flight to Beijing was uneventful, but I think I told you we were being transferred to a train for an overnight ride into central China, to the city of Luoyang.

We arrived in Beijing around 3 pm, and had until 10:30 to wander—with a  guide who was quite agreeable. She took us to Tiananmen Square (largest public place in the world–no one was watching us, Kevin Eack, except some of your CIA types!), and to my great surprise few people

guide who was quite agreeable. She took us to Tiananmen Square (largest public place in the world–no one was watching us, Kevin Eack, except some of your CIA types!), and to my great surprise few people

were there. When I have been there in the past, it’s been mobbed. I also learned that there’s a flag ceremony in the evening, when they take down the flag—and I’ve been getting folks up at sunrise (4:30 here) when we could be going to the square at 7 at night…..Glad no one found out!

The guide asked about a meal, and took us to a Shanxi restaurant, where we ate cat ears. Before you think this is standard fare in China, let me tell you that it is not “cat ears,” but a pasta dish shaped like cat ears (least I hope it was!). Dinner for four cost $15, which told me we were no longer in Hong Kong.

We still had some time, so the guide took us to a Beijing Opera performance. If you have never seen “Farewell my Concubine,” the film is a great introduction to Chinese opera. It is a combination of acrobatics and high-pitched singing, banging gongs, and a whole lot more fun than it sounds.

Then to the train station, where 9 million people gather. Fortunately, there is a separate waiting room for the “soft sleeper” passengers, and I have learned that is the best way to travel in China on an overnight train–it’s only 4 to a compartment. We settled in at 11:30 for the ride, which got us to Luoyang at 9:30 this morning.

David likes North China–he says it is more like Illinois in food, and looking out the window, he remarked, “We’re in Indiana.” They grow some corn, but lots of wheat that is featured in noodle dishes (and cat ears!).

Luoyang is a “small city” of 2 million, with around 6 million total in the suburbs. It’s a grey city, but like most Chinese cities, has increased splashes of color recently. It was prominent in the past, one of 8 cities (can you name the others) that served as capital of China. It accommodated 12 dynasties, most recently the northern Sung in the 10th century, which was way before my time.

Luoyang is a “small city” of 2 million, with around 6 million total in the suburbs. It’s a grey city, but like most Chinese cities, has increased splashes of color recently. It was prominent in the past, one of 8 cities (can you name the others) that served as capital of China. It accommodated 12 dynasties, most recently the northern Sung in the 10th century, which was way before my time.

Yes, before MY time.

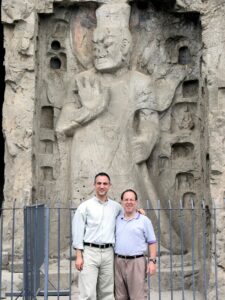

The Longmen grottoes–Buddhist caves with statues carved by emperors, their concubines currying favor, empresses, and officials–are world class, and dominate two sides

of the Yi River. I shot about 50 digital shots, and probably will keep 49. The Tang statues are plump, the Northern Wei slender, so I will be able to tell them apart. Maybe.

of the Yi River. I shot about 50 digital shots, and probably will keep 49. The Tang statues are plump, the Northern Wei slender, so I will be able to tell them apart. Maybe.

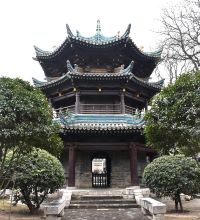

There were two other major sights on the itinerary. In talking with the guide, I learned the Guang Gong is buried here–at least  his head is. He is the statue I collect since I think he is fiercer than Tommy Titan, and I’d like to use the GG as the IWU mascot. He was a general in the period of the Three Kingdoms, and he was slain. His head was sent to the emperor at Luoyang, who attached a wooden body (!) and buried him with honors. There is now a temple on the spot that dates (in its present form) from the Ming dynasty (1500s),

his head is. He is the statue I collect since I think he is fiercer than Tommy Titan, and I’d like to use the GG as the IWU mascot. He was a general in the period of the Three Kingdoms, and he was slain. His head was sent to the emperor at Luoyang, who attached a wooden body (!) and buried him with honors. There is now a temple on the spot that dates (in its present form) from the Ming dynasty (1500s), that is a quiet spot in a noisy world. The Guang Gong is a symbol of loyalty (a scout is loyal!). I’ll show you the statue I bought here.

that is a quiet spot in a noisy world. The Guang Gong is a symbol of loyalty (a scout is loyal!). I’ll show you the statue I bought here.

The other place dates from around 65 BC, when the first Indian monks brought Buddhism to China, to the White Horse Temple. After getting through the hawkers who wanted to sell us things we did not want, including pictures on a white horse that they told us (at least I think that was their Chinese) had brought the sutras back from India to Luoyang, the temple was one of the best preserved I’ve seen in China.

The other place dates from around 65 BC, when the first Indian monks brought Buddhism to China, to the White Horse Temple. After getting through the hawkers who wanted to sell us things we did not want, including pictures on a white horse that they told us (at least I think that was their Chinese) had brought the sutras back from India to Luoyang, the temple was one of the best preserved I’ve seen in China.

In other words, though Luoyang is only #9 on the list of places to visit in China, it is really a pretty neat place.

The sun finally peaked out this afternoon for the first time in a week. Hope it stays!

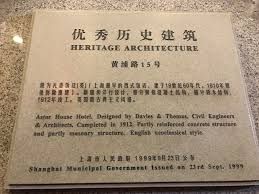

I am mentally still in Shanghai. The old city–in these pictures–still in my head. The old Palace Hotel from 1906, where I have stayed; the Broadway Mansions, a mid-30s creation. It was headquarters of the American military during the Chinese Civil War.

I am mentally still in Shanghai. The old city–in these pictures–still in my head. The old Palace Hotel from 1906, where I have stayed; the Broadway Mansions, a mid-30s creation. It was headquarters of the American military during the Chinese Civil War.

As for China, a few comments:

As for China, a few comments:

the garden, despite being surrounded by 24 million people.

the garden, despite being surrounded by 24 million people.

There, I went to hell. Many have told me that’s where I should go, but the boat stopped at Fengdu, which has a “ghost city,” that includes hell. There were all sorts of Taoist spirits–including one that deals with wine–I pictured some of the fraternity boys there! I stopped there 8 years ago, when I took my first Yangtze trip, and there was still a city there. Since then, the river has risen due to the impoundment created by the Three Gorges

There, I went to hell. Many have told me that’s where I should go, but the boat stopped at Fengdu, which has a “ghost city,” that includes hell. There were all sorts of Taoist spirits–including one that deals with wine–I pictured some of the fraternity boys there! I stopped there 8 years ago, when I took my first Yangtze trip, and there was still a city there. Since then, the river has risen due to the impoundment created by the Three Gorges Dam, and the 150,000 people have been relocated to the south bank, the old city destroyed and removed.

Dam, and the 150,000 people have been relocated to the south bank, the old city destroyed and removed. already done is cause the city of Ichang (where we disgorged, so to speak) to increase tenfold—from 400,000 to

already done is cause the city of Ichang (where we disgorged, so to speak) to increase tenfold—from 400,000 to a “small” Chinese city of 4 million.

a “small” Chinese city of 4 million. electricity (5-10 percent of China’s needs), flood control (a major problem in the past), a transportation artery into the interior, and–this was new to me–a potential source of water for the parched north (including Beijing, which has major shortfalls in water supply). The world said, it is environmentally unsound to build the dam, and you lack the technology, etc. 12 years later, the dam is in place, and it will be fully functional in two years.

electricity (5-10 percent of China’s needs), flood control (a major problem in the past), a transportation artery into the interior, and–this was new to me–a potential source of water for the parched north (including Beijing, which has major shortfalls in water supply). The world said, it is environmentally unsound to build the dam, and you lack the technology, etc. 12 years later, the dam is in place, and it will be fully functional in two years. May 13, 2006

May 13, 2006 1) Xi’an is a walled city, with the existing wall first built in the late 14th century. The Communists finally completed rebuilding it, which led to a 14k bike ride one cool morning. The wall was not finished last time I was there.

1) Xi’an is a walled city, with the existing wall first built in the late 14th century. The Communists finally completed rebuilding it, which led to a 14k bike ride one cool morning. The wall was not finished last time I was there.

4) We visited two Buddhist pagodas, including one where Xuan Zang brought the original books from the Buddha in the 8th century.

4) We visited two Buddhist pagodas, including one where Xuan Zang brought the original books from the Buddha in the 8th century. varieties…quite a meal.

varieties…quite a meal.

We spent the day traveling to a Buddhist grotto where a serious monk had carved statues in in the late Sung dynasty period–our guide gave a great explanation of how Buddhism embraced both existing Chinese religions–Confucianism and Taoism.

We spent the day traveling to a Buddhist grotto where a serious monk had carved statues in in the late Sung dynasty period–our guide gave a great explanation of how Buddhism embraced both existing Chinese religions–Confucianism and Taoism. cuisines of China, so we went to a local restaurant for a hot pot. I bought some spices and if they make it home, we will try one on a campout. You chop everything and put it in boiling soup with spices, and take it out a few minutes later.

cuisines of China, so we went to a local restaurant for a hot pot. I bought some spices and if they make it home, we will try one on a campout. You chop everything and put it in boiling soup with spices, and take it out a few minutes later. most capitals, imperious and imperial. The old is impressive, the new, impressive if you have my perspective, which goes back to 1990. There has been a controversy about the Starbucks (gasp) in the Forbidden City. I suspect it will be gone eventually, along with the mayor who approved it. Ironically, it is an internet citizen crusade that has been spearheading the demand for its demise.

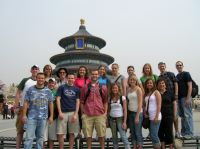

most capitals, imperious and imperial. The old is impressive, the new, impressive if you have my perspective, which goes back to 1990. There has been a controversy about the Starbucks (gasp) in the Forbidden City. I suspect it will be gone eventually, along with the mayor who approved it. Ironically, it is an internet citizen crusade that has been spearheading the demand for its demise. The city is preparing for the Olympics, and refurbishing its sights, which means there were several places (including the Forbidden City) which were “forbidden” because they were closed or parts were closed. One morning, I took some students to my favorite park (Jing Shan) which overlooks the Forbidden City. It’s where the last Ming emperor hanged himself (in 1644).

The city is preparing for the Olympics, and refurbishing its sights, which means there were several places (including the Forbidden City) which were “forbidden” because they were closed or parts were closed. One morning, I took some students to my favorite park (Jing Shan) which overlooks the Forbidden City. It’s where the last Ming emperor hanged himself (in 1644).

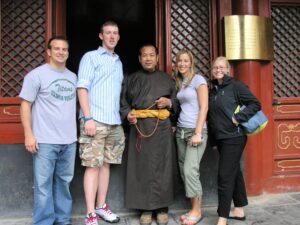

the temples. Ruth Ann needed to shop, but wanted also to see one of the temples, so we escorted about half the students to the Lama Temple, which was the location of the Tibetan monks in Beijing. It’s one of my favorite places anyway–with the half-man, half-animal versions of the Buddha followers. Having been to Tibet gave me a new perspective.

the temples. Ruth Ann needed to shop, but wanted also to see one of the temples, so we escorted about half the students to the Lama Temple, which was the location of the Tibetan monks in Beijing. It’s one of my favorite places anyway–with the half-man, half-animal versions of the Buddha followers. Having been to Tibet gave me a new perspective. and some without water), and traditional shopping. That was neat, since there’s a tea shop that JR and I discovered two years ago, revisited last year, and he was there in March. We spent about an hour with the owner, sampling teas (I do like the lichi red and 8 treasures, which are not available in the US) and departed with tea and memories. We took the subway around and felt like real Beijingers.

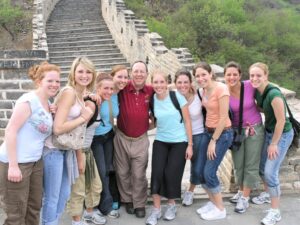

and some without water), and traditional shopping. That was neat, since there’s a tea shop that JR and I discovered two years ago, revisited last year, and he was there in March. We spent about an hour with the owner, sampling teas (I do like the lichi red and 8 treasures, which are not available in the US) and departed with tea and memories. We took the subway around and felt like real Beijingers. civilizations (as I sometimes think we do–we have little that’s a thousand years old) to walk the Sacred Way (to the tombs of the Ming emperors), or to walk through the Forbidden City for the coveted audience with the emperor or to walk the Great Wall and realize that it was built almost 2000 years ago. Pretty

civilizations (as I sometimes think we do–we have little that’s a thousand years old) to walk the Sacred Way (to the tombs of the Ming emperors), or to walk through the Forbidden City for the coveted audience with the emperor or to walk the Great Wall and realize that it was built almost 2000 years ago. Pretty  overwhelming

overwhelming hours, but overnight, so we got on and were on for most of the evening. We arrived in Xian in time to visit several Buddhist pagodas from 600 ad, to have dumpling dinner, and to wander through the Muslim area.

hours, but overnight, so we got on and were on for most of the evening. We arrived in Xian in time to visit several Buddhist pagodas from 600 ad, to have dumpling dinner, and to wander through the Muslim area.