It’s been 140 years since the first Labor Day holiday was planned and celebrated in New York City. Labor organizers, municipalities, and states adopted the holiday over the next several years, until it became a federal holiday in 1894.

The late 1800s were a chaotic time in the US, as everyone was in some way effected by the huge transition from a largely agricultural society to an industrial society. The 1880s saw an influx of labor strikes, with workers challenging poor or dangerous working conditions and long hours. In the May of 1894, thousands of workers at Pullman Palace Car Company went on strike. Later that summer, a federal judge issued an injunction against a sympathy boycott and President Cleveland sent troops in to enforce the boycott. With the arrival of federal troops, the Pullman strike ended violently. Congress had just passed legislation in June, making the first Monday in September a holiday to recognize and celebrate the contributions of laborers, which Cleveland signed into only a few days before sending troops to Illinois.

That sympathy boycott might not have been necessary. The local and national organizations behind the strike and boycott had refused membership to Pullman’s two thousand African-American porters. Marginalized and minoritized persons were typically barred from joining labor organizations at the time, and thus had a completely different experience in their fair labor battles.

Legislation since then has continued to intentionally exclude women and People of Color and conversations around labor often erase the roles non-white men played in securing labor protections.

This Labor Day, in addition to enjoying the time with friends and family, check out some of the resources Ames Library has that shine a light on the pivotal contributions of BIPOC men and women in the labor movement.

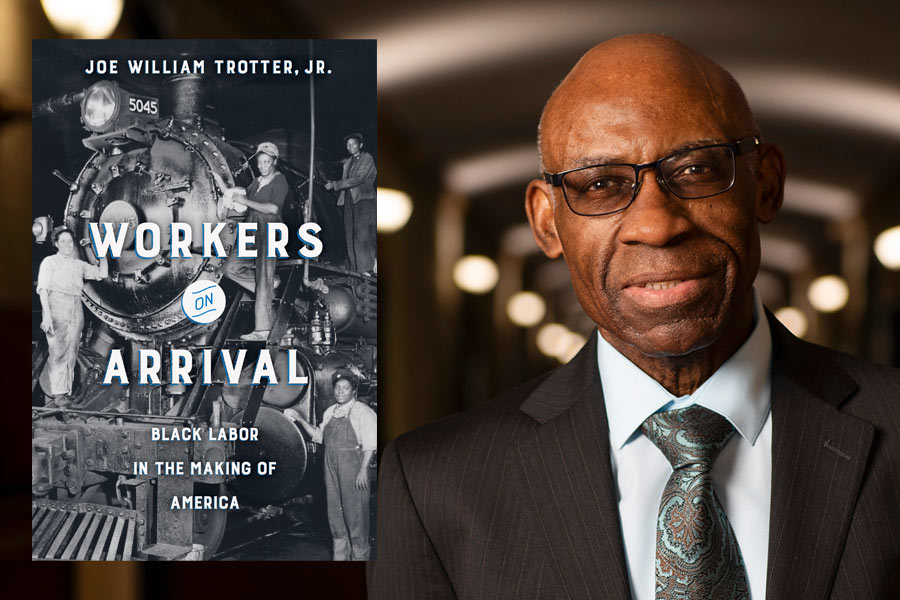

Covering the last four hundred years since Africans were first brought to Virginia in 1619, Trotter traces black workers’ complicated journey from the transatlantic slave trade through the American Century to the demise of the industrial order in the 21st century. At the center of this compelling, fast-paced narrative are the actual experiences of these African American men and women.

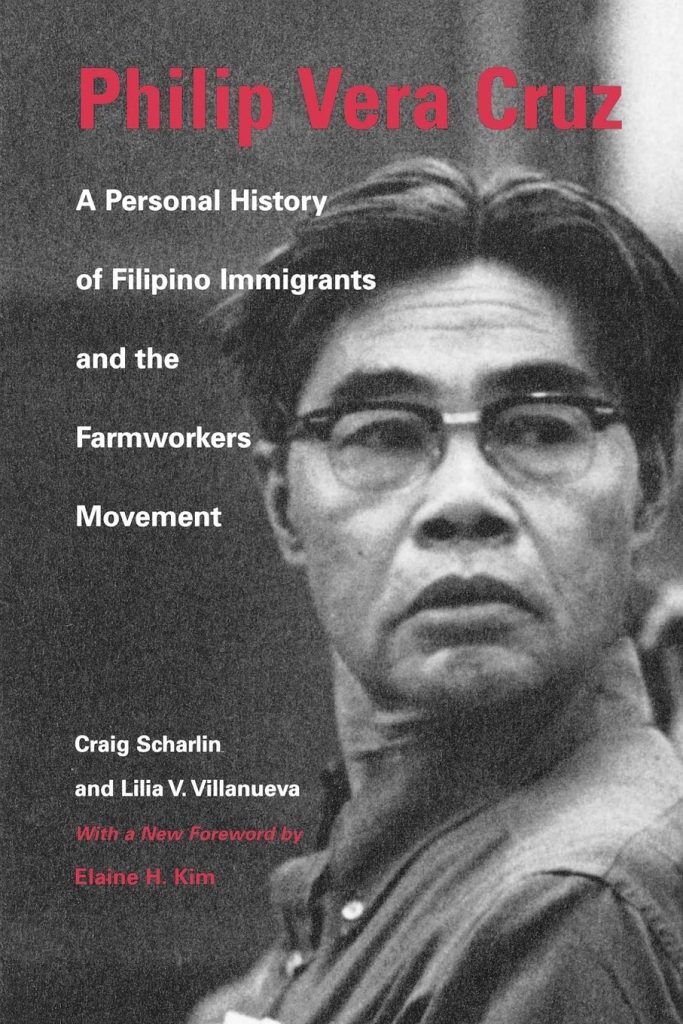

Filipino farmworkers sat down in the grape fields of Delano, California, in 1965 and began the strike that brought about a dramatic turn in the long history of farm labor struggles in California. Their efforts led to the creation of the United Farm Workers union under Cesar Chavez, with Philip Vera Cruz as its vice-president and highest-ranking Filipino officer.

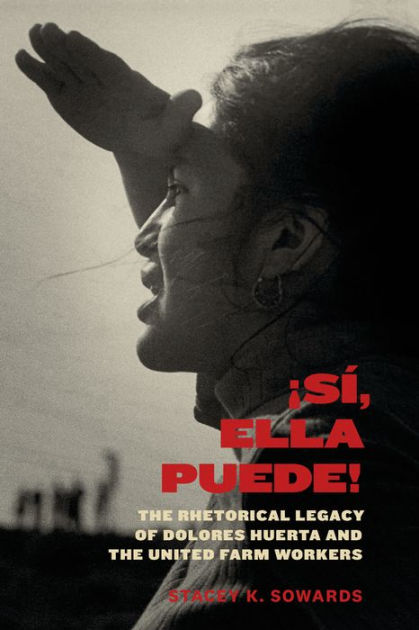

Since the 1950s, Latina activist Dolores Huerta has been a fervent leader and organizer in the struggle for farmworkers’ rights within the Latina/o community. A cofounder of the United Farm Workers union in the 1960s alongside César Chávez, Huerta was a union vice president for nearly four decades before starting her own foundation in the early 2000s.