Jago Morrison’s paper, “Jihadi fiction: radicalisation narratives in the contemporary novel” is available online, published 6 March 2017 by the Taylor & Francis Group. Here’s the abstract (link to full text also available):

“As Ulrich Beck suggests in World at Risk, fear of Islamist extremism has become a dominant strand in contemporary perceptions of risk. In the media, a set of ‘stock’ radicalisation narratives have emerged in which, typically, a misguided loner is brainwashed into embracing a violent perversion of Islam. In the background, the wider Muslim community is accused of a dangerous complicity and complacency. This essay explores some notable attempts in fiction to unpick such popular radicalisation narratives. In novels by John Updike and Sunjeev Sahota, the psychological and faith dimensions of suicide bombing are a key focus, attempting to explore from the inside, how an educated young Muslim might be impelled along the path to martyrdom. In texts by Mohsin Hamid and J.M. Coetzee, the ideological staging of ‘radicalisation’ and ‘fundamentalism’ themselves is brought into question. Current counterterrorist measures include indefinite detention of US citizens without trial, while in the UK, over two million public sector workers have been recruited to the largest surveillance exercise ever codified in British law. In this context, the essay shows how recent fiction has attempted to trouble the frames of representation through which a perpetual state-of-emergency is passed off as our ‘new normal.'”

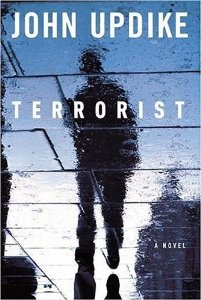

“In John Updike’s Terrorist,” Morrison writes, “both radicalisation and its contexts are portrayed rather differently. Again, the focus of the novel is to explore the risk of a devastating suicide attack, but to do so through an individual, human story. This, however, is very much an American tale, in which the impulse towards extremism is seen as rising, at least in part, out of the bleakness and inanity of contemporary suburban life. Like Sahota, Updike begins by drawing a protagonist who is damaged and ripe for influence. No visit to Afghanistan is required for Ahmad: between the machinations of a local imam and those of a CIA agent, the manipulations all happen close to home, in an ordinary city modelled on Paterson, New Jersey. In Updike’s portrayal, Ahmad is an impressionable and (somewhat cartoonishly) zealous American teenager, product of a broken home and in search of self-esteem. Raised non-religious after his Egyptian father abandoned him as a young child, he is described by his mother as ‘trusting’ and ‘easily led.’”

“In John Updike’s Terrorist,” Morrison writes, “both radicalisation and its contexts are portrayed rather differently. Again, the focus of the novel is to explore the risk of a devastating suicide attack, but to do so through an individual, human story. This, however, is very much an American tale, in which the impulse towards extremism is seen as rising, at least in part, out of the bleakness and inanity of contemporary suburban life. Like Sahota, Updike begins by drawing a protagonist who is damaged and ripe for influence. No visit to Afghanistan is required for Ahmad: between the machinations of a local imam and those of a CIA agent, the manipulations all happen close to home, in an ordinary city modelled on Paterson, New Jersey. In Updike’s portrayal, Ahmad is an impressionable and (somewhat cartoonishly) zealous American teenager, product of a broken home and in search of self-esteem. Raised non-religious after his Egyptian father abandoned him as a young child, he is described by his mother as ‘trusting’ and ‘easily led.’”

Updike, Morrison concludes, “takes a primarily psychologising approach. Traumatically affected by the loss of his father—like Sahota’s character Imtiaz—[Ahmad] is presented as a perfect target for grooming.”

Later he writes, “Updike includes Qur’anic references, to suggest Ahmad’s rediscovery of Islam. When we look at his formulation, however, it is not difficult to see the family resemblance between the epiphany depicted here and the idea of revelation celebrated by the author’s own Barthian Christianity. At the moment of truth, Ahmad recognises the immanence of divine creation in the everyday – with the lapsed Jew Levy beside him and in the spectacle of the black children in the car in front, ‘lovingly dressed and groomed by their parents, bathed and soothed every night.’ of ‘sacrifice’, as Karl Barth describes it in The Epistle to the Romans. Sacrifice for Barth is ‘not a human action whereby he who makes the sacrifice becomes thereby an instrument of God,’ as Rashid has encouraged Ahmad to believe. Sacrifice lies in the humble acknowledgement of divine creation and in the effacement, rather than the assertion of will or ego. It is a ‘return to His mercy and freedom.’

“This epiphany, in which Jew and Muslim, white and black are saved together in a Barthian revelation of Divine Love is clearly, in one sense, a self-consciously utopian gesture. How far it takes the novel forward in terms of elucidating either the psychology, or the political and ideological context to suicide bombing, however, is less clear. In the context of intensifying Islamophobia in US political discourse, Updike’s attempt to voice not only an alternative Muslim perspective, but an Islamist’s deep disgust with contemporary American society, is bold indeed. As with Sahota, however, it is interesting to see that, in the words of the Wall Street Journal’s reviewer, ‘Mr. Updike cannot quite make the turn from this confused boy to the life-destroyer that a terrorist must be.'”