Back in Windhoek from Scout camp—er, Etosha National Park.

In mid-May 1983, I became Scoutmaster of Troop 19. Accordingly, mid-May 2016, it’s not surprising that I commemorated this auspicious event by camping—albeit in a “rest camp” in a national park in Namibia.

We didn’t get much rest, though, because Etosha National Park is one of the  largest preserves in the world. Created in 1907 under the Germans, it was once almost 50,000 square miles. It’s now closer to 15,000, but still substantial. Etosha means “great white place,” and it is: one of the major features (about ¼ of it) is a salt pan, which does fill if there’s enough rain—but hasn’t for nearly 8 years. The salt pan shimmers white, looking for all the world like a distant ocean.

largest preserves in the world. Created in 1907 under the Germans, it was once almost 50,000 square miles. It’s now closer to 15,000, but still substantial. Etosha means “great white place,” and it is: one of the major features (about ¼ of it) is a salt pan, which does fill if there’s enough rain—but hasn’t for nearly 8 years. The salt pan shimmers white, looking for all the world like a distant ocean.

But it’s not the salt pan we came to see; it was to work on Nature requirements, and Etosha does have a strong “merit badge” program. There’s a variety of ways you can study nature:

- Go to a museum. Or the National Park variant covered in the story told by Eagle Scout Chris Perillo, who, when we saw an alligator swimming in the ‘Glades,’ told us he’d just come back from the North Cascades where his family took a nature hike at night. The ranger said she’d been there earlier in the day, and there was an owl—and she pointed her flashlight at the tree, and sure enough the owl was still there. This continued till the end, when she asked Chris to say behind—and carry the stuffed animals back. That’s the origin of my comment about “automated” or “robotic” or “animals on demand”on hikes. That wasn’t a problem for us.

- A second variant is to go to a game park. Our guests did this at various stops while we were in our business visits, and got some great pictures feeding cheetahs. You’re sure to see animals, which is also true if you go to a zoo.

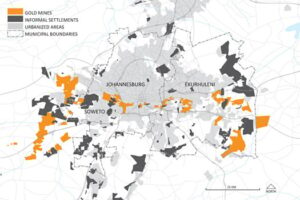

- The private preserves like I went to last year (adjoining Krueger National Park in South Africa) offer a different blend. Lots of animals, but they’re like fish in the sea. The sea has a lot of fish, but you can’t always find them. At Sabi-Sabi, the driver plus tracker were radioed in to other vehicles, though, and we were able to spot lots of wildlife, and because it was a private preserve, pursue them off the road.

- Etosha was a great challenge (and excitement, really) because you never knew what you were going to see, and you couldn’t go off road in pursuit.You might be fortunate enough to have an old bull elephant almost close enough to touch as he went across the road, which our vehicle did, or see a leopard dragging a kill, which some of our other trekkers did.

I chose plan A, which was to have “only” three game drives—but one was from 6:15 am until 5:30 pm, and took us from our rest camp across to the other end of the park.

It was easy enough to meet the requirement to identify 10 different animals, and here are some we saw:

Lots of antelope. Some of their relatives we had for dinner, since they’re vegetarians and generally at the bottom of the predator food chain. I know why lions love impala (I do too), oryx (on the Namibian seal, but also on the menu as schnitzel or lasagna), kudu (menu item, too, but a big one), and the South African rugby team mascot, the springbok.

Lots of antelope. Some of their relatives we had for dinner, since they’re vegetarians and generally at the bottom of the predator food chain. I know why lions love impala (I do too), oryx (on the Namibian seal, but also on the menu as schnitzel or lasagna), kudu (menu item, too, but a big one), and the South African rugby team mascot, the springbok.

The bigger mammals. The giraffe has an lovely gait, and it was just fun to watch them. They move both left legs at the same time, then the two right legs—so they’re always in step, but I wonder why they don’t topple. Other animals like to hang around with them because they can spot the carnivores a long distance away, and that’s a plus. The black rhino, who have bad eyesight, (and are an endangered species partly because they can’t see the poachers) are just one of the animals with a symbiotic relationship with giraffes.

watch them. They move both left legs at the same time, then the two right legs—so they’re always in step, but I wonder why they don’t topple. Other animals like to hang around with them because they can spot the carnivores a long distance away, and that’s a plus. The black rhino, who have bad eyesight, (and are an endangered species partly because they can’t see the poachers) are just one of the animals with a symbiotic relationship with giraffes.

The others: I said our group didn’t see many cats, but we saw their followers—the jackals and hyenas that our guide called “cowardly,” but I think they’re smart—like people, they let others get the food for them; the  honey badger, that looks like a skunk and inhabited our campground going from garbage can to garbage can; the banded mongoose, who scurried from a furtive feast in a termite hill when we stopped to photograph them, like boys caught doing something wrong; zebras all over the place, looking like painted horses; and the wildebeest and warthogs. I thought we ought to have an “ugliest” contest, but they’d probably all enter—and all win. Check out wildebeest and see whether you think all babies are beautiful.

honey badger, that looks like a skunk and inhabited our campground going from garbage can to garbage can; the banded mongoose, who scurried from a furtive feast in a termite hill when we stopped to photograph them, like boys caught doing something wrong; zebras all over the place, looking like painted horses; and the wildebeest and warthogs. I thought we ought to have an “ugliest” contest, but they’d probably all enter—and all win. Check out wildebeest and see whether you think all babies are beautiful.

The highlight for me—as those of you who know me might guess—was the discovery at the east entrance of the park of the original German fort, built in 1907 to block the entrance of diseased cattle into German lands. It’s now a hotel in that rest camp.

The highlight for me—as those of you who know me might guess—was the discovery at the east entrance of the park of the original German fort, built in 1907 to block the entrance of diseased cattle into German lands. It’s now a hotel in that rest camp.

Well, summer camp is over, I’ve completed my Nature requirements, so I think I’ll go on a high adventure trip to Ethiopia. That begins tomorrow morning, as my new best friends scatter, some going home, some staying in Africa for more adventures.