Feliz Navidad.

If you saw my smile on Facebook when I was at the bottom of Castillo San Felipe, the largest fort anywhere in the Spanish colonies, you can imagine how much wider it was today when I actually got to scale the fort to take pictures at the top.

Built after Francis Drake ransacked the city and held it hostage for 120,000 ducats, the Spanish government freed the funds to finally build the fort as part of the walls and fortifications to protect Cartagena from future pirate raids. The Fort did that, helping repel French forces in

the 1690s (part of an ongoing struggle with Louis XIV that culminated in the War of Spanish Succession). But the ultimate challenge was during the War of Jenkin’s Ear (1739-1741)—look that one up in your history books—when Admiral Vernon gathered 23000 troops and laid siege to the city. He was so confident of victory that he prepared victory medals. In vain. A veritable handful of Spanish soldiers, aided by the unhealthy climate—yellow fever, typhus, and malaria were rampant – sent the English packing. One of Vernon’s aides, incidentally, was Lawrence Washington, George’s stepbrother, who named his big house Mt. Vernon, supposedly in honor of his chief.

the 1690s (part of an ongoing struggle with Louis XIV that culminated in the War of Spanish Succession). But the ultimate challenge was during the War of Jenkin’s Ear (1739-1741)—look that one up in your history books—when Admiral Vernon gathered 23000 troops and laid siege to the city. He was so confident of victory that he prepared victory medals. In vain. A veritable handful of Spanish soldiers, aided by the unhealthy climate—yellow fever, typhus, and malaria were rampant – sent the English packing. One of Vernon’s aides, incidentally, was Lawrence Washington, George’s stepbrother, who named his big house Mt. Vernon, supposedly in honor of his chief.

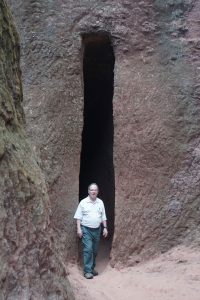

The fort’s chief feature was its size, and its ability to command the harbor. It was the jewel in a system of forts that blocked access to the harbor here. It’s not self contained—apparently, troops usually came down to the city for barracks. There’s an elaborate tunnel system connecting different parts of the fort, though, and, obviously, an arresting view of the old city. To the other side, Cartagena spouts modern skyscrapers, a casino, McDonald’s, a beach, and the nickname, “Little Miami.”

The fort’s chief feature was its size, and its ability to command the harbor. It was the jewel in a system of forts that blocked access to the harbor here. It’s not self contained—apparently, troops usually came down to the city for barracks. There’s an elaborate tunnel system connecting different parts of the fort, though, and, obviously, an arresting view of the old city. To the other side, Cartagena spouts modern skyscrapers, a casino, McDonald’s, a beach, and the nickname, “Little Miami.”

The other part of the day I spent in the Naval museum, housed in what was once a Jesuit college, next to what is still now  (again) a Jesuit church. The ticket taker tried her best to cool my interest (“No change” meant I had to walk back to the hotel—currency here has lots of zeros; $1 US is about 3300 Colombian pesos—to make sure I could get in), then attempted to dissuade me by telling me the exhibits were all in Spanish (and the guidebook in English was “not for sale”). Undeterred, I went in and discovered “no habla espanol” didn’t mean I couldn’t read most of the posters; indeed, the exhibits were mostly posters, with some artifacts, talking about a history of the Caribbean, which was mostly a battle between the lawful Spanish exploiters and the unlawful enemies of El Rey de Espana. And the wealth of Spain in the New World certainly attracted Spain’s European enemies. As part of the mercantilist school of thought, colonies existed to make money for the mother country, and so the empires attempted to forbid trade with other powers. That led to a lot of smuggling, a lot of resentment, and by the end of Spanish rule, was one of the reasons for independence.

(again) a Jesuit church. The ticket taker tried her best to cool my interest (“No change” meant I had to walk back to the hotel—currency here has lots of zeros; $1 US is about 3300 Colombian pesos—to make sure I could get in), then attempted to dissuade me by telling me the exhibits were all in Spanish (and the guidebook in English was “not for sale”). Undeterred, I went in and discovered “no habla espanol” didn’t mean I couldn’t read most of the posters; indeed, the exhibits were mostly posters, with some artifacts, talking about a history of the Caribbean, which was mostly a battle between the lawful Spanish exploiters and the unlawful enemies of El Rey de Espana. And the wealth of Spain in the New World certainly attracted Spain’s European enemies. As part of the mercantilist school of thought, colonies existed to make money for the mother country, and so the empires attempted to forbid trade with other powers. That led to a lot of smuggling, a lot of resentment, and by the end of Spanish rule, was one of the reasons for independence.

The museum gave a nice picture (easier to understand than the words) of the steady deterioration of the Spanish empire, and the gradual friendship with England forged in the wars against Napoleon that led Britain (and the United States, though not for the same reason) to stay out of the Latin American wars of Independence.

Dinner put a nice end cap on our anniversary celebration. I asked the concierge for a recommendation (as I’d been doing every night) and he suggested a Cartagena restaurant which had local dancing/music, English speaking waiters (a plus), and a local menu. I had shredded rabbit, figuring that was not a dish I’d likely get at home. It was far enough to take a cab there, but on the way home, we stopped a carriage, which took us around the old town on our way back to the former convent we’ve called home for the past week.

Tomorrow back to the Midwest. I suppose if I think centigrade, the difference in temperature won’t seem so extreme. It’s been in the upper 80s here during the day, though the mornings (when I’ve gone biking) have lower humidity, nice breezes, around 75 temperature, and almost no one on the streets.

See you soon.