The guidebooks say that there are four must-dos in Beijing. We did two of them yesterday—climb the Great Wall and eat Peking duck.

The Great Wall is one of China’s relics from ancient times. It runs from the ocean nearly 3,000 miles into the Taklamakan Desert, ending at Jiayuguan on the Silk Road. Consolidated nearly 2,000 years ago by the First Emperor (he of the underground army at Xi’an fame), the current incarnation dates from the Ming Dynasty (or where we were, reconstructed in the last 10 years). Meant to keep the barbarians from the north out (the very Mongols JR and I are traveling to visit beginning Saturday), it failed when put to the test (the Mongols came through in the 14th century and Kublai Khan  became emperor of China, with his capital at Dadu, Beijing), and the Manchurians came through (and ruled from 1644 until 1911 as the Qing Dynasty).

became emperor of China, with his capital at Dadu, Beijing), and the Manchurians came through (and ruled from 1644 until 1911 as the Qing Dynasty).

The Great Wall remains impressive. Guides used to say it was the only man-made object visible from space, but I think truth-in-advertising laws made that claim obsolete. The nearest the wall comes to Beijing is about 20 miles, and that’s where we made our pilgrimage (Mao is reputed to have said you’re not a hero until you’ve climbed the Great Wall, and we’re heroic). The area was a crisscross of walls (it was a key pass; Beijing is surrounded by mountains on the north), but we chose the steepest. My GPS said we climbed over 1,000 feet in ½ a mile of horizontal distance. Someone steeped in math said that averages about a 36% gradient, and it certainly seemed that steep. Maybe steeper.

But the wall is not the only Great thing to do. On the way, tourists get whisked to the Ming Tombs, an area which contains the remains of 14 emperors, assorted empresses, and two tombs for the concubines (the other Ming emperors were buried in Nanking, which was their original capital), but for me the impressive part of the tombs is the Sacred Way. For about a mile, there is a walkway that contains statues of the animals and imperial servants waiting to serve the emperor in the afterlife. It’s an impressive testimony to the solemnity and wealth of the imperial family—and like much of Beijing, a model for other countries influenced by the Chinese. There’re much more modest examples in Korea (I’ve been to the tomb of King Sejong, who gave the country its alphabet) and Vietnam (I’ve been to the tombs of the Nguyen Dynasty in Hue).

The Ming were not the first rulers of China to have a Sacred Way, but they are the closest to Beijing. For example, I’ve been to the tomb of the Empress Wu (the only woman to have been the emperor of China) near Xi’an, and it has an enormous Sacred Way. What emphasizes the importance of the tombs is that the Qing dynasty founder (whose tomb is in Shenyang) had one constructed for the last Ming emperor, who hanged himself in the park across from the Forbidden City.

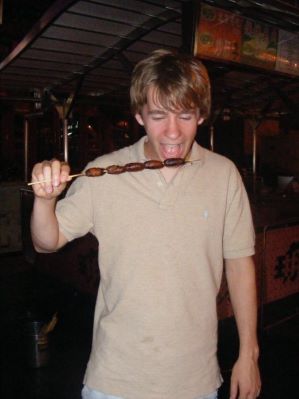

The other activity yesterday was the Peking duck dinner, one of the “musts” in Beijing. Over the years, my students have come to refer to it as “duck burritos” since the duck gets sliced and put into a crepe-like pancake, with onions, plum sauce, and cucumbers. Invariably, someone doesn’t like it, which means I can usually eat more than I should, but less than I want.

The other activity yesterday was the Peking duck dinner, one of the “musts” in Beijing. Over the years, my students have come to refer to it as “duck burritos” since the duck gets sliced and put into a crepe-like pancake, with onions, plum sauce, and cucumbers. Invariably, someone doesn’t like it, which means I can usually eat more than I should, but less than I want.

As for great things, today (Thursday), we continued to sample the delights of a city that has been the capital of China for nearly 600 years, and is imperial in every sense of the word. The morning began with a visit to the Temple of Heaven. Probably the second most familiar building in Beijing (after the Bird Nest and maybe before the Forbidden City), the Temple played an important role in dynastic survival for nearly 500 years. In an agricultural society (then as now), bountiful harvests ensured the survival of the regime. Hence, the emperor’s efforts to tease rain and ensure bountiful harvests made this Temple (to Heaven, not to a Buddha) significant in the empire.

The current emperors read history and also know that unruly peasants have overthrown numerous dynasties. At least twice a year the imperial presence  trooped from the Palace to the Temple to speak, as only the Emperor could, directly to Heaven, and slaughter the calves or whatever was necessary to feed the people and ensure the stability of the dynasty. This function was so important that when Korea became an empire in 1905 to try to block the Japanese, the king turned emperor built his own temple of heaven. The importance of agriculture (then as now) helped foreign experts (then being the Catholic missionaries, who came with some astronomical knowledge) gain entrée to the Court in Beijing.

trooped from the Palace to the Temple to speak, as only the Emperor could, directly to Heaven, and slaughter the calves or whatever was necessary to feed the people and ensure the stability of the dynasty. This function was so important that when Korea became an empire in 1905 to try to block the Japanese, the king turned emperor built his own temple of heaven. The importance of agriculture (then as now) helped foreign experts (then being the Catholic missionaries, who came with some astronomical knowledge) gain entrée to the Court in Beijing.

An added benefit was a stay at the Tiantan park (where the Temple is located), which is a mecca for retired people to play cards, musical instruments, dance, do tai chi and exercise. It is mostly my generation that gets up in the morning, takes their canaries in cages and other birds to the park, and spends time with friends. Younger Chinese, like younger Americans, either are at work, or played too hard the night before to be in the park, as we were, by 8:30 a.m.

Beijing has other Great things, and we visited them, too, relics of the days when China was the most powerful nation in the world, the middle kingdom between heaven and earth, and the model for nations in the region. In the 1790s, the Qianlong emperor told a British delegation that the west had nothing China wanted or needed, a statement that was pretty much true until the British started selling opium from India….but that’s another story.

The Qianlong Emperor, who ruled for nearly 60 years, was responsible for building what has always been one of my favorite temples—the Lama Temple, which was his way of saying China is multicultural because it is the largest (and maybe the only) Tibetan temple in Beijing. He converted a prince’s home into a Tibetan temple which houses the largest standing Buddha in the world. As for the Tibetan version, Buddhism tends to absorb and blend with local religions, and Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia is recognizably Buddhist, but its adherents reflect the preexisting demons—there’s a blue-headed demon for example that were I DePaul, would make the mascot. And having been to Tibet, I can recognize more of the differences between the lama Yellow Hat version and the more basic Chinese version.

Near the Lama Temple is the center of the traditional civil service (from the Yuan dynasty to 1908)—the local Confucian temple and the attached university where for nearly 500 years the best scholars in the nation studied the analects of Confucius to prepare themselves for the meritocracy (at its best) that constituted the civil service. At an annual exam, students competed for the right to be officials in the dynastic service; the successful candidates (14,000+ anyway) have their names posted on stone steles for posterity. The “library” has over 100 stone books with 620,000 characters in the Analects of Confucius, the book for the exam for the career.

Our guide told me an interesting story about the Confucian temple that I think shows why people interested in contemporary China should understand the past. She said when she was in college, her teacher’s daughter was applying for college. The teacher took her daughter to the Confucian temple to pray. Sure enough, she got into the school she wanted, which led to her returning and giving thanks.

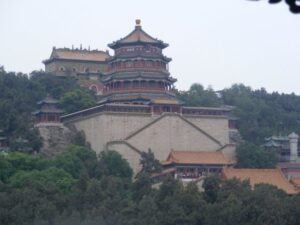

The final site was the Summer Palace, thronged with visitors because today is part of a four-day holiday centering on dragon boat racing in the south and the making of a sticky rice item that is exclusive to the holiday. A sign at the palace indicated that there had been 11,000 visitors yesterday, expected 18,000 today, and probably 25,000 over the weekend. There’s a man-made lake with pavilions for residence of officials and the emperor (the Empress Dowager Cixi, who ruled China for much of its late 19th and early 20th century decline, moved the court to the Summer Palace in the summer from  1903 until her death in 1908). Lost in the walking through the longest covered corridor that has paintings from novels and Chinese scenery are reminders that Western troops ravaged the palace in 1860 and again after the Boxer Uprising, so what we see has been mostly rebuilt in the last century; and reminds us that China has endured a century of humiliation that is an anachronism in Chinese history.

1903 until her death in 1908). Lost in the walking through the longest covered corridor that has paintings from novels and Chinese scenery are reminders that Western troops ravaged the palace in 1860 and again after the Boxer Uprising, so what we see has been mostly rebuilt in the last century; and reminds us that China has endured a century of humiliation that is an anachronism in Chinese history.

Our farewell dinner was in a “theme park,” the theme being the Imperial Court, a fitting theme given what we’ve seen in Beijing. We came to a former prince’s house that had been taken over by a Hong Kong restaurateur (recently), and retrofitted to look like the Manchus had returned. We had yellow everything (the yellow being the color of the Emperor exclusively), imperial food (including lily and a “concubine’s smile” salad). The servers were dressed in court elegance, and spoke Manchu to us (with an occasional and needed translation into English). An appropriate ending to a 3-week long trip that began with our arrival in Bangkok almost exactly 3 weeks ago.

I said I’d say a few words about what I’ve seen in China. Bear in mind it’s based mostly on what I’ve seen in Beijing, and, despite what Beijingers think, Beijing is the capital of China; it is not China.

Our visit to John Deere highlighted one of the most important issues re: the current government of China—the need to generate at least 8% growth to maintain political and economic stability. That’s challenged in two ways—the first is that China depends a lot on the economic climate elsewhere in the world. That’s a problem; almost 30 million workers in factories that make the goods for the rest of the world went home for the New Year’s Holiday in January and were told not to come back. Further, the importance of tourism, and the existence of a reasonably-priced, world class infrastructure of hotels and restaurants, demands tourists. Tourism is down here, too.

China’s response seems to be to encourage domestic consumption of goods and services. The bailout package here is toward consumers—to purchase cars and appliances, perhaps speeding up the embourgeoisement of the world that Marx predicted, and something that has been happening more and more quickly in the 19 years I’ve been visiting China.

The second challenge, as the Deere manager made clear, is the need for China to feed itself. I marvel as I look out the window of the train at how intensively China cultivates its arable land (much of China is not good for farming). It’s not enough. Yet making agriculture more efficient (the average farm is 1 acre, and if 300 million Chinese left the farm for the city, the average-size farm would still be under 5 acres) presses the need to find more jobs. Hence, the challenge to the regime isn’t from “democracy,” but from those forces that have granted or removed the mandate of heaven for thousands of years in the past—the need for prosperity at home and prestige and security abroad.

The smorgasbord of Asia ends for the class members with their flight back to the United States tomorrow. It’s only a 20-minute flight by the clock; they leave Beijing at 4:10 and land at O’Hare at 4:30, no mean feat. Parents, collect your sons and daughters, mindful that they’ve had a frame-breaking change experience. Someday, they’ll thank me, hopefully in my lifetime.

As my reward, I get to go on to Mongolia. As the Chinese saying goes, “Yi lu ping an.” May you have a peaceful journey.

An old city at the southern entrance to the Straits of Malacca, through which pass over half of the shipping of the world, Malacca traces its history back to the 13th century or so, when an Indonesia prince (the connections between Indonesia and Malaysia are pretty strong even today; Bahasa is spoken in both countries, both are Muslim, and Sumatra, one of the over 2,000 islands that constitutes Indonesia, is 1-½ hours away by ferry on the other side of the straits) came here and had his dogs outfoxed (that sounds wrong) by a mouse deer, a small and now endangered species, under a Malacca tree. The sultan built a dynasty that lasted until 1513, when the Portuguese wrested away control of the city, beginning several centuries of Portuguese rule. The famous Cheng Ho, featured occasionally on the History Channel, visited here, and has a small corner in the history museum. There’s a rebuilt Istana (palace) of the sultan, which I can see from the window in my hotel, but Malacca is one of the four states in Malaysia now with no sultan.

An old city at the southern entrance to the Straits of Malacca, through which pass over half of the shipping of the world, Malacca traces its history back to the 13th century or so, when an Indonesia prince (the connections between Indonesia and Malaysia are pretty strong even today; Bahasa is spoken in both countries, both are Muslim, and Sumatra, one of the over 2,000 islands that constitutes Indonesia, is 1-½ hours away by ferry on the other side of the straits) came here and had his dogs outfoxed (that sounds wrong) by a mouse deer, a small and now endangered species, under a Malacca tree. The sultan built a dynasty that lasted until 1513, when the Portuguese wrested away control of the city, beginning several centuries of Portuguese rule. The famous Cheng Ho, featured occasionally on the History Channel, visited here, and has a small corner in the history museum. There’s a rebuilt Istana (palace) of the sultan, which I can see from the window in my hotel, but Malacca is one of the four states in Malaysia now with no sultan.

But the complex was more than just an over-the-top mall. It included an elegant hotel (pictured elsewhere), two theme parks (one water based, one with roller coasters and other non-liquid treats)—AND a university. Now that’s buzz.

But the complex was more than just an over-the-top mall. It included an elegant hotel (pictured elsewhere), two theme parks (one water based, one with roller coasters and other non-liquid treats)—AND a university. Now that’s buzz.