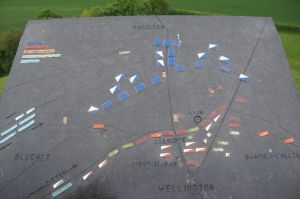

Some of us took advantage of this cool rainy afternoon to view the battlefield that marked the end of an effort to create a “European union”—the battlefield where Napoleon (if you remember the 50s song) met his Waterloo. I did not realize it was close to Brussels, but it’s less than 10 miles outside the city; being a fan of short megalomaniacs, I had to go see it.

When Napoleon escaped from Elba, and rallied his soldiers, he thought he might have a chance at splitting the coalition reunited against him if he  struck a quick blow. At Waterloo, he tried to keep the Prussian and Anglo-Dutch armies from uniting against him. Slowed by rain (imagine that!), in June 1815, his armies struck too late to prevent the Prussians from joining

struck a quick blow. At Waterloo, he tried to keep the Prussian and Anglo-Dutch armies from uniting against him. Slowed by rain (imagine that!), in June 1815, his armies struck too late to prevent the Prussians from joining  with Wellington, and, according to the movie, allowed Wellington’s armies to gather where they could not be destroyed by French artillery. In a 10 hour battle, around 170,000 troops decided the fate of Napoleonic France.

with Wellington, and, according to the movie, allowed Wellington’s armies to gather where they could not be destroyed by French artillery. In a 10 hour battle, around 170,000 troops decided the fate of Napoleonic France.

In a sense, the battle underscores what we’ve been learning in Brussels—the difficulty of unifying Europe short of war. That’s the message we’re taking from our visits to members of the European Union civil service staff—the people most committed to making “Europe” work. For example, yesterday’s speaker raised a point I had not considered—a simple but complex one involving the basis of legal codes. While the British have evolved common law (it’s common to us, too), much of Europe uses the Code Napoleon. As I noted to the speaker, Louisiana uses the Code Napoleon in the US, which should give Europeans hope that the legal systems can actually mesh. His comment: “the EU is ahead of its time.”

Today’s speaker gave a slightly different view of the origins of the European Union that helped me understand some of its functioning. I think he described the evolution in terms of “shared sovereignty”—in which the members have given up authority over certain areas, and created an organizational structure to oversee laws in those areas. In other words, if the treaties have conceded pollution controls to a “High Authority” (as the European Commission was once known), the legislation Parliament passes on that topic is enforceable in all countries—whether they voted for it or not. His comment was that it is an unprecedented “experiment.” When he noted it has been going on for 60 years, my response was that after 60  years, the United States had not yet sorted out many of the issues that “We the People” wrote a constitution to settle; I hoped it doesn’t take a civil war to resolve Europe’s issues.

years, the United States had not yet sorted out many of the issues that “We the People” wrote a constitution to settle; I hoped it doesn’t take a civil war to resolve Europe’s issues.

One other thing we’re taking from our EU visits is the focus of the European Union on social issues—and more general r&d support. I remember from my last trip in Eastern Europe that much of the infrastructure support for roads, for example, in the Baltic countries, came from EU support. In addition, one of our speakers in Paris was a Ph.D. (from Illinois) working on a project involving DNA, that was based on a 7 billion Euro grant. Think about an American working on pure research in Europe….

If you want a business epigram on why the EU needs to continue to exist—when I left London, I had not spent or exchanged all my British pounds. I took a 20 pound note to the exchange, worth about 31$ and got back (after fees and commission) about 15 Euro, or about 21$. Imagine doing that every time you crossed a border!

As for Brussels itself, home to NATO as well as the EU, cold wet days are not uncommon—and they are ideal for spending time in museums, which we’ve also done. My three favorites included two as impressive for the buildings as for the contents—the buildings were art nouveau, and the museums helped spare the wrecking ball. One was a comic strip museum—after all the adventurous Tintin came from the brush of a Belgian artist— who has been translated in dozens of languages around the world. The second museum of note was the Musical Instruments Museum, housed in a former Art Nouveau department store. When I entered, I was given an audio guide; as I passed the exhibits, the instrument featured played. If you’ve never heard a cabinet organ, you’ve missed a real treat, as I would have had I not gone to the museum. The third museum is on the grand place, a medieval square I mentioned yesterday, with Gothic and Baroque homes. Professor Pana and I went to the “House of the King,” which was a wonderful Gothic building with period pieces, art, sculpture, and pictures of the city, some of them following Louis XIV bombardment that leveled 4000 houses.

who has been translated in dozens of languages around the world. The second museum of note was the Musical Instruments Museum, housed in a former Art Nouveau department store. When I entered, I was given an audio guide; as I passed the exhibits, the instrument featured played. If you’ve never heard a cabinet organ, you’ve missed a real treat, as I would have had I not gone to the museum. The third museum is on the grand place, a medieval square I mentioned yesterday, with Gothic and Baroque homes. Professor Pana and I went to the “House of the King,” which was a wonderful Gothic building with period pieces, art, sculpture, and pictures of the city, some of them following Louis XIV bombardment that leveled 4000 houses.

Well, we leave Brussels for Berlin via Cologne with good memories of  Brussels—the Manneken-Pis (look that one up; it’s the symbol of the city); the chocolate (world famous!), and lapin (rabbit) and moule (mussels) meals. That moule meal was facilitated by an IWU alum, George Kambouroglou, who works as a software supervisor at the EU. We’ve been in touch with George as soon as we learned he was in Brussels, and the ’93 graduate of IWU bent over backward to make sure we had as

Brussels—the Manneken-Pis (look that one up; it’s the symbol of the city); the chocolate (world famous!), and lapin (rabbit) and moule (mussels) meals. That moule meal was facilitated by an IWU alum, George Kambouroglou, who works as a software supervisor at the EU. We’ve been in touch with George as soon as we learned he was in Brussels, and the ’93 graduate of IWU bent over backward to make sure we had as  much information as he could find, and, even though he left with his family for the US this morning, joined us for dinner last night at Café Leon to reminisce about his days as an Acacia/physics major at IWU.

much information as he could find, and, even though he left with his family for the US this morning, joined us for dinner last night at Café Leon to reminisce about his days as an Acacia/physics major at IWU.

On to Berlin.

From what’s been called Europe’s last “artificial” country—Brussels

From what’s been called Europe’s last “artificial” country—Brussels

Most of the traffic in the Louvre, not surprisingly, was in the European section, where it has a strong holding in pictures of and about the French Revolution (not the collection of the Bourbons!)—Ingres and David and Delacroix, for example, with the famous painting of Napoleon’s coronation ala Charlamagne, where I think he took the crown from the Pope and put it on his own head.

Most of the traffic in the Louvre, not surprisingly, was in the European section, where it has a strong holding in pictures of and about the French Revolution (not the collection of the Bourbons!)—Ingres and David and Delacroix, for example, with the famous painting of Napoleon’s coronation ala Charlamagne, where I think he took the crown from the Pope and put it on his own head.

We spent the afternoon at the Chateau of Versailles, begun as a modest hunting lodge for Louis XIII, but expanded by his son, the Sun King Louis XIV, to become the premier castle, and I believe the largest, certainly in Europe, and one that puts Windsor Castle into the minor leagues. The world class attraction seemed to have attracted the world this Sunday, as the rooms were as crowded as could be. 46,000 workers labored to bring the finest the French monarchy could obtain to the Chateau. It came close to bankrupting France, a process that culminated, when the spending to fight Britain and incidentally help the US gain independence, precipitated the French Revolution. In the meantime, the Bourbon kings (XIV, XV, XVI—sounds like super bowls, don’t they) enjoyed the facilities. They say Louis XIV built it, XV enjoyed it, and XVI paid for it. We had a lively discussion involving those who have traveled elsewhere in Europe, and the closest rivals we could come up with were St. Petersburg—and the Vatican St. Peters.

We spent the afternoon at the Chateau of Versailles, begun as a modest hunting lodge for Louis XIII, but expanded by his son, the Sun King Louis XIV, to become the premier castle, and I believe the largest, certainly in Europe, and one that puts Windsor Castle into the minor leagues. The world class attraction seemed to have attracted the world this Sunday, as the rooms were as crowded as could be. 46,000 workers labored to bring the finest the French monarchy could obtain to the Chateau. It came close to bankrupting France, a process that culminated, when the spending to fight Britain and incidentally help the US gain independence, precipitated the French Revolution. In the meantime, the Bourbon kings (XIV, XV, XVI—sounds like super bowls, don’t they) enjoyed the facilities. They say Louis XIV built it, XV enjoyed it, and XVI paid for it. We had a lively discussion involving those who have traveled elsewhere in Europe, and the closest rivals we could come up with were St. Petersburg—and the Vatican St. Peters.

Budapest and Lvov come to mind–sought to mimic the leafy boulevards, the wide streets, the victory monuments, and the 6 story buildings with the mansard roofs (go to the Art Institute and see the Impressionist section and you’ll see why Paris caught the fancy of urban planners and urbanites in the 19th century).

Budapest and Lvov come to mind–sought to mimic the leafy boulevards, the wide streets, the victory monuments, and the 6 story buildings with the mansard roofs (go to the Art Institute and see the Impressionist section and you’ll see why Paris caught the fancy of urban planners and urbanites in the 19th century).

invited two of his coworkers (boss?), who described the nature of private banking to us. As they explained, they provide customer services to a limited clientele—the really wealthy in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (from this area), with a heavy emphasis on benefitting “cash rich” customers.

invited two of his coworkers (boss?), who described the nature of private banking to us. As they explained, they provide customer services to a limited clientele—the really wealthy in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (from this area), with a heavy emphasis on benefitting “cash rich” customers. crisis of the past few years, there are about 250,000 finance people in England, down from 350,000 at the onset of the crisis. In describing how to get through the barrier, they emphasized the study of foreign languages—everyone in Europe seems to know several, and some of the Universities in England pay for their students to study abroad for a year—and to “network like crazy; make every connection count.”

crisis of the past few years, there are about 250,000 finance people in England, down from 350,000 at the onset of the crisis. In describing how to get through the barrier, they emphasized the study of foreign languages—everyone in Europe seems to know several, and some of the Universities in England pay for their students to study abroad for a year—and to “network like crazy; make every connection count.”