July 28, 2013 Split

We came to Split to get aboard the Athena, our home for the next 11 days. However, I chose this trip partly because Split was one of the places I HAD to visit—it houses (literally) one of the finest Roman ruins of Late Antiquity, the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian.

We came to Split to get aboard the Athena, our home for the next 11 days. However, I chose this trip partly because Split was one of the places I HAD to visit—it houses (literally) one of the finest Roman ruins of Late Antiquity, the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian.

The Emperor, who apparently was born in Illyria (the Roman province we call Dalmatia in honor of one of the first Illyrian tribes to settle here—the Dalmatia, but equally well known for the dogs which Disney made famous!) at what was then the nearby capital, Salona. Inheriting an empire in shambles, Diokles (his Greek name), was quite a warrior. He reconquered Egypt (which accounts for the sphinx in the palace, transported from Thutmose’s tomb, as well as columns from Aswan, used to build the palace), but decided that the empire was too big to succeed, and accordingly, appointed a co-emperor, and two successors. Having stabilized the government, and reorganized the military, after 20 years on the throne, he abdicated as emperor, and got his co-emperor to do the same, elevating the successors as co-emperors of the Roman empire. Until Diocletian, our guide quipped, Rome changed emperors in the late 4th century as often as babies changed diapers.

He retired to his palace in Split, which he’d spent 10

He retired to his palace in Split, which he’d spent 10  years building, employing 20,000 workers to surround the son of Jupiter (as he was wont to call himself, as the last pagan emperor) with the splendor he had known in Nicomedia (where he was based; it’s near Istanbul). The result was a walled enclosure 750 feet long and 450 feet wide that housed military, religious, administrative, and residential quarters, with 16 gates (3 of which still stand) and a number of towers (none standing). One impressive feature—since he was the emperor, he could not go up and down stairs, so the whole complex—being built on the Adriatic, had to be level, requiring an extensive foundation that has since been excavated, revealing the superior architecture of late Roman antiquity.

years building, employing 20,000 workers to surround the son of Jupiter (as he was wont to call himself, as the last pagan emperor) with the splendor he had known in Nicomedia (where he was based; it’s near Istanbul). The result was a walled enclosure 750 feet long and 450 feet wide that housed military, religious, administrative, and residential quarters, with 16 gates (3 of which still stand) and a number of towers (none standing). One impressive feature—since he was the emperor, he could not go up and down stairs, so the whole complex—being built on the Adriatic, had to be level, requiring an extensive foundation that has since been excavated, revealing the superior architecture of late Roman antiquity.

After his death, some subsequent emperors used the palace, but eventually  a city grew up within, especially using the walls as one of their walls. It is mostly this jumble of medieval and ancient that greets the visitor today; as our guide noted (he was funny!), it’s probably the only 1700 year old ruin where you can see people hanging underwear to dry.

a city grew up within, especially using the walls as one of their walls. It is mostly this jumble of medieval and ancient that greets the visitor today; as our guide noted (he was funny!), it’s probably the only 1700 year old ruin where you can see people hanging underwear to dry.

In other ways, the results were not what Diocletian might have anticipated. He might have been right in anticipating that the Empire, as constituted, was too big to succeed, but his tetrarchy (2 emperors, two successors) might have worked in his reign—a statue of the four looking harmonious, was carted from Constantinople by Crusaders to St. Marks in Venice, where it remains today—but the rise of Constantine and the creation of Constantinople (the new Rome) marked the end of the successful Eastern and Western Emperors. Rome never became the capital again, and the last Western Emperor (by some reckoning), died in the palace in Split in 480. Even Split came, eventually, under Venetian rule, as the Eastern Empire crumbled after 1204, when the 4th crusade got misdirected on its way to Jerusalem, capturing, sacking, and ruling the Byzantine Empire for a half century; Venice took many of the former Byzantine possessions, ruling some areas of the Adriatic until Napoleon ended the Venetian Republic (our Croat guides were bitter about the Italian connection, noting the Venetians forbade the use of Croatian; she added that when Croatians drove out the Germans and Italians in World War II they also destroyed many of the Venetian relics that still remained).

The biggest irony of Diocletian’s palace, though, involved his mausoleum. Diocletian was buried in the palace. He was also known for his persecution of Christians—many Saints date from his efforts to suppress Christianity. He even executed his wife and daughter when he discovered they had become Christians.

The biggest irony of Diocletian’s palace, though, involved his mausoleum. Diocletian was buried in the palace. He was also known for his persecution of Christians—many Saints date from his efforts to suppress Christianity. He even executed his wife and daughter when he discovered they had become Christians.

When Constantine issued his declaration on tolerance of Christianity, and eventually converted to Christianity, the Christian community in Split eventually (in the fifth century) converted the mausoleum to a church, destroying Diocletian’s sarcophagus, and 200 years later, the mausoleum designed to house the remains of Diocletian, worshipped as a god by the Romans, became a Cathedral, home of the archbishop of Split. It is still in use as a church today. We left just before the mass started this morning.

touting the “first declaration of human rights,” a 1463 announcement from Mehmet the Conqueror that his newly-acquired subjects in Bosnia were free to practice their religion. Though it was honored on and off in Ottoman history (people of the Book—as they referred to Jews and Christians—were usually tolerated), but I think paid extra taxes and could not serve in the military. Captured Christian children, however, were frequently raised Muslim, and became the shock troops of the janissaries, the infantry of the Ottomans, but the 20th century relations with Greeks (perhaps beginning with the war for Greek independence in the 1820s), Armenians, and Kurds was and is troubled.

touting the “first declaration of human rights,” a 1463 announcement from Mehmet the Conqueror that his newly-acquired subjects in Bosnia were free to practice their religion. Though it was honored on and off in Ottoman history (people of the Book—as they referred to Jews and Christians—were usually tolerated), but I think paid extra taxes and could not serve in the military. Captured Christian children, however, were frequently raised Muslim, and became the shock troops of the janissaries, the infantry of the Ottomans, but the 20th century relations with Greeks (perhaps beginning with the war for Greek independence in the 1820s), Armenians, and Kurds was and is troubled.

was nervous), and took us close up and up and over. What a great view from the air, and what a smooth ride. We landed on the trailer, and celebrated with champagne. It was 7 am.

was nervous), and took us close up and up and over. What a great view from the air, and what a smooth ride. We landed on the trailer, and celebrated with champagne. It was 7 am.

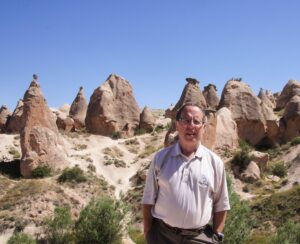

this until the snows come—and it gets bitterly cold, our guide says, with lots of snow. Some of that is obvious when I look out my window at the volcano largely responsible for the eruptions that created Cappadocia—it’s over 4000 meters, or over 12,000 feet, still snowcapped, and betraying that volcano shape that hides the fact that the last eruption was 2 million years ago, and the guide assured me it was dormant.

this until the snows come—and it gets bitterly cold, our guide says, with lots of snow. Some of that is obvious when I look out my window at the volcano largely responsible for the eruptions that created Cappadocia—it’s over 4000 meters, or over 12,000 feet, still snowcapped, and betraying that volcano shape that hides the fact that the last eruption was 2 million years ago, and the guide assured me it was dormant. that have eroded in various ways; the scenery consists of “fairy chimneys” and rock formations that could be in the Great Sand Dunes, hoodoo type formations with balanced rocks on top; I think the description of one valley is “like the moon,” and another is called imagination valley, where our guide was able to point out formations that looked like “Napoleon’s Hat,” etc.

that have eroded in various ways; the scenery consists of “fairy chimneys” and rock formations that could be in the Great Sand Dunes, hoodoo type formations with balanced rocks on top; I think the description of one valley is “like the moon,” and another is called imagination valley, where our guide was able to point out formations that looked like “Napoleon’s Hat,” etc.

fact, the guest house where I’m staying is a modified cave house. They created whole villages in the “fairy chimneys,” rather like the Puebloan in the Southwest—except the homes were individual, and not communal, though we did see some communal kitchens. Like the native Americans at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, the

fact, the guest house where I’m staying is a modified cave house. They created whole villages in the “fairy chimneys,” rather like the Puebloan in the Southwest—except the homes were individual, and not communal, though we did see some communal kitchens. Like the native Americans at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, the

there were still some magnificent churches, partly because of the importance of Cappadocia in church history. I had Eusebius as bishop of Caesarea, which he was—in Palestine—but there were three local Saints that were featured in the churches here.

there were still some magnificent churches, partly because of the importance of Cappadocia in church history. I had Eusebius as bishop of Caesarea, which he was—in Palestine—but there were three local Saints that were featured in the churches here.

and had to catch the plane for Cappadocia at 5 am, which made me glad I had nothing else scheduled today when I got to Ushidar, one of the “cities” in the area. The gateway to Cappadocia is Kayseri, a town the Romans called Caesarea. Yes, the empire stretched from London through Asia minor, and through much of north Africa. One of the prominent early Christians in the biography of Constantine I’m reading was Bishop Eusebius, and tomorrow I guess I’ll get to see remains of the old churches. What’s interesting is the landscape, sort of like being in the Badlands—except that people carved homes and churches and hid from authority, especially, for about 700 years.

and had to catch the plane for Cappadocia at 5 am, which made me glad I had nothing else scheduled today when I got to Ushidar, one of the “cities” in the area. The gateway to Cappadocia is Kayseri, a town the Romans called Caesarea. Yes, the empire stretched from London through Asia minor, and through much of north Africa. One of the prominent early Christians in the biography of Constantine I’m reading was Bishop Eusebius, and tomorrow I guess I’ll get to see remains of the old churches. What’s interesting is the landscape, sort of like being in the Badlands—except that people carved homes and churches and hid from authority, especially, for about 700 years.

, the tomb with the sculptures of Alexander the Great drawing the most attention; the King buried in it had battled on the side of Alexander, and the frieze commemorates their relationship.

, the tomb with the sculptures of Alexander the Great drawing the most attention; the King buried in it had battled on the side of Alexander, and the frieze commemorates their relationship.

enjoyed was “Istanbul through the Ages,” an exhibit that featured what was and what is, with some wonderful explanations of what happened. I learned, for example, that Bosphorus means “ox ford,” and it came to prominence when Darius and the Persians used a series of boats as a bridge to advance to battle the Greeks; I think one of the monuments to the Greek victory eventually wound up in Istanbul. (Is it time for Greece to get indignant?)

enjoyed was “Istanbul through the Ages,” an exhibit that featured what was and what is, with some wonderful explanations of what happened. I learned, for example, that Bosphorus means “ox ford,” and it came to prominence when Darius and the Persians used a series of boats as a bridge to advance to battle the Greeks; I think one of the monuments to the Greek victory eventually wound up in Istanbul. (Is it time for Greece to get indignant?)

area on the other side of the Golden Horn to the Dolmabahce Palace. I was not prepared for the 1850s neoclassical and rococo palace Abdulhamid built to replace the Topkapi Palace and indicate Turkey was a European power at a time when the Ottomans were desperately trying to modernize to keep the empire together. Greece had already sought its independence; I think Egypt had gotten its; Turkey, England and France were fighting Russia in the Crimea—and Abdulhamid had spent money building a palace that rivaled the big

area on the other side of the Golden Horn to the Dolmabahce Palace. I was not prepared for the 1850s neoclassical and rococo palace Abdulhamid built to replace the Topkapi Palace and indicate Turkey was a European power at a time when the Ottomans were desperately trying to modernize to keep the empire together. Greece had already sought its independence; I think Egypt had gotten its; Turkey, England and France were fighting Russia in the Crimea—and Abdulhamid had spent money building a palace that rivaled the big ones in Western Europe. My favorite room reflects the efforts of Germany to woo the Ottomans—a vase from Kaiser Wilhelm, with his picture on it, and a statue and picture of Otto von Bismarck, the German chancellor during the last half of the 19th century, as Germany and the Ottoman Empire forged the ties that helped bind them in a death dance in World War I based on their common enmity to Russia that would topple both the German and Ottoman Empires (as well as their Austro-Hungarian allies)

ones in Western Europe. My favorite room reflects the efforts of Germany to woo the Ottomans—a vase from Kaiser Wilhelm, with his picture on it, and a statue and picture of Otto von Bismarck, the German chancellor during the last half of the 19th century, as Germany and the Ottoman Empire forged the ties that helped bind them in a death dance in World War I based on their common enmity to Russia that would topple both the German and Ottoman Empires (as well as their Austro-Hungarian allies)