The 10th Annual Faculty Development in International Business-Africa program, to be conducted in South Africa and Namibia May 09 – 23, 2016, will combine over two dozen business visits, cultural experiences and academic visits and lectures over 14 days, to initiate and/or enhance faculty awareness and insight in the business, academic and cultural world of sub-Saharan Africa. For the fifth consecutive year, a concurrent “guest program” will be offered as well. Business and academic visits will include: Wits University, University of Namibia, U.S. Consulate, U.S. Embassy, Massmart, Discovery Health, Dimension Data, Coca-Cola, SABMiller, Johannesburg Stock Exchange, Export Processing Zone, Industrial Development Corporation, Women’s Entrepreneurship Program, and local NGO’s. Cultural and Eco-Tourism visit include Namibia’s Skeleton Coast and Etosha Naitonal Park, as well as city tours of Johannesburg, South Africa and Windhoek, Namibia.

Some thoughts on South African businesses

Johannesburg

Marketers know that a strong finish colors the entire consumer experience.

If that’s the case, the South Carolina FDIB certainly planned this trip well. We concluded our business visits today, having come the 800 miles from Lusaka early this morning, with what might be the best visit of the trip. We went to Dimension Data, an IT subsidiary of Japan’s NTC, the telecom giant, where we were hosted by Derek Wilcox, a South African who has been with company as it has grown to major global status, where it is now an $8 billion corporation, operating in 58 countries with 27,000 employees. Mr. Wilcox is the COO of Asian and Middle Eastern operations, and thus was in a position to enlighten us on the IT industry, his company, Africa and the Middle East, and South Africa.

The company started in 1983 in manufacturing and gravitated to provide applications, installation, maintenance, and other services, which now provide 50% of sales and 75% of profits. (My students who have read “Going Downstream” will understand the value of the shift!). It was at one time the exclusive distributor for Cisco, and is still one of its biggest partners.

His outline of African business was especially interesting because it covered the entire continent; he divided the continent basically into regions: 1) the Mediterranean countries, which he said were still recovering from the Arab Spring; 2) the oil producers, particularly Ghana and Nigeria (he had a lot to say about Nigeria, which has the largest population in Africa, and by some accounts, the largest GDP, with Lagos being the business center); 3) the East Coast countries which are starting to discover gas, and 4) the African hub starting to consolidate around Kenya. Despite its political troubles with Somalia, he thought East Africa is an attractive area, rapidly developing, and noted that Kenya has a big agribusiness market in Europe (bear in mind, if it’s winter in Europe, it’s summer down here, ala Chile and Peru and the US market); and 5) southern Africa. He thought one of the countries to keep an eye on was Botswana, a potential model for sound government (not common on the continent), but with an economy still based on diamonds, cattle, and tourism.

As for South Africa itself, he pointed out that South Africa contributes 40% of African income and 40% of that comes from two neighborhoods in Johannesburg, including Sandton, where our hotel is located; however, the country’s strength is weakening both absolutely and relatively, having, he suggested, lost its political and social way. Like many business men, he chafed at the use of funds for addressing social needs, describing the state as having more social safety nets than many Scandinavian countries. At the same time he acknowledged the need to redress the inequalities that mark wealth distribution in the Republic. We’d heard from others as well about some of the problems of the African National Congress, which has ruled South Africa since democracy emerged in 1994, and he, too, thinks the rise of an opposition party (which has taken over the Western Cape) will be a healthy step.

He described South Africa as a relatively difficult place to do business, with exchange controls, an elaborate effort to promote Black Enterprises, and a strong labor force that supports and is supported by the African National Congress (and, in addition, one of our faculty noted that South Africa will start requiring in-person visits to a consulate to get a visa, making it more difficult to tour or work as an expatriate in the country) ; as evidence of the erosion of South Africa’s global status, he noted the declining number of companies (from 95% to 80%, he estimated) that base their African operations in South Africa. Instead, many have located or relocated to the United Arab Emirates. He thought those governments had shrewdly expanded Emirates and Qatar airlines, which have some of the most extensive routes in the world, world class facilities, and a welcoming government. He did observe the disadvantages, though, such as that the UAE does not have a rule of law, while South Africa has a well-established judicial system.

Some summary thoughts on my observations about sub-Sahara businesses:

1) The role of the United States. The African Growth and Opportunities Act, recently renewed by Congress, is generally praised as a positive contribution to the African economies, reducing tariffs on African products imported into the United States. Ambassador Taylor gave high marks to the US’s anti HIV campaign, too, and it’s obvious, from the visits we’ve had, the embassies are promoting American investments and non-government activities. Still, as Wilcox pointed out, there’s a belief that Americans are the latest exploiters, who simply want to make short-term profits for shareholders. He noted that US AID gives money—which must be spent in the United States.

2) There was a copy of the China Daily in the lobby of our hotel today, an indication of the importance of the topic that keeps surfacing: the presence of China. China has supported a lot of the independence movements in Africa from the beginning, and has continued supporting many African governments and economies with no strings attached. Chinese build dams and roads and railroads—and mushroom “factories.” They give grants to send African students to Chinese universities. However, the relationship is becoming a little frayed. The Chinese are disappointed with some of their “investments,” such as Mugabe in Zimbabwe, and Africans are concerned about the cliquishness of overseas Chinese and the traders who are perceived to be stealing African jobs.

3) South Africa sometimes thinks of itself as a big brother especially to its neighbors. If it’s going to be a model, it needs, I think, to behave better. The Joburg newspaper today had the defense of the president’s $21 million expenses for his house: he needed, it stated, the visitor center to protect his privacy, and the cattle corral to keep the cattle from interfering with the security infrastructure, etc. If I had a big brother like that…. Still, South Africa is further along the development curve than the rest of the continent, and has a hand in lots of business on the continent. It has also played peacemaker on occasion.

4) As for what we’ve seen overall, the metaphor that comes to mind was at Kafue. That small town in Zambia, on the main North-South highway from Lusaka to Livingstone, had a sign advertising the opening of a mall, with retail space available. At the time we passed by, we could see that some of the foundation for some of the buildings had been started. That location is business Africa for me: the foundations have started in some places, but the mall is still a distance away from being built.

In 24 hours, most of us will be on an airplane back to the US, with a lot of experiences to share with our classes.

Copper is King, but …

Lusaka Airport

Copper May Be King, but Zambia is a Democracy

Yesterday we visited the Chamber of Mines, a lobbying group for the mining industry, and learned basically that the industry is troubled, despite its importance to the economy. It produces 68% of the country’s exports, 30% of its government revenue, 9% of GDP, almost 4% of investments, and 1.7 % of employment, according to industry figures. It’s had a turbulent past, having been nationalized at one point. Some of the problems are peculiar to Zambia, and align with what we’ve heard before: that landlocked Zambia has borders with 8 African countries (and the borders can produce long delays—it’s 6 weeks to and from Durban, making for high transportation costs; contrast with Chile, where nowhere is far from the Pacific). Some are endemic to industry in general; as a revenue producer, it’s susceptible to being targeted by politicians and the public for contributing more through taxation. There seems to be little government discussion with the mining industry; one of the executives pointed out that he learned about new taxes only by reading the newspaper. Taxes have also escalated. Furthermore,I don’t think mining has a good reputation anywhere (see the latest Grisham novel about West Virginia mines or read the newspapers about Chinese coal mine deaths, for example), and the aging mines here seem vulnerable to political pressure. When asked why, if conditions are so unfavorable here, there was no move to pull up and pull out, the answers ranged from, “We’ve got too much invested,” to a belief that in the long haul it’s possible, to some ego-based beliefs “we can do it.” The executives included some Zambians and a few foreigners, one of whom had been in the industry for 35 years, and I’d love to have questioned him about his experiences elsewhere. As I said, copper may be king, but Zambia is a democracy.

We also visited the University of Lusaka, purportedly the 3rd best university in the country. It’s an unabashedly for-profit business that has returned 33% dividends to investors. Read backward from its $1000 per semester tuition, and you see a university with strict cost controls: 14 full time faculty and over 160 adjuncts and absolutely modest facilities. Its mission is “To fulfill the ever growing demand for employable human capital in various industries through continuous interaction with” etc., focusing on “tailor made programmes whilst equipping this human capital with cutting edge skills knowledge and information.” If offers doctoral programs in business, but “Other areas of specialization can be given consideration by the University Senate.” Its campus is spartan (the library had one shelf of business books, mostly texts, and two of law; the classrooms have whiteboards but no visible technology) but has almost 5000 students, mostly from Zambia and Zimbabwe. The University borrowed $200,000 to build the current campus, which it paid off in two years, a mark again of its efficiency.

We also visited the University of Lusaka, purportedly the 3rd best university in the country. It’s an unabashedly for-profit business that has returned 33% dividends to investors. Read backward from its $1000 per semester tuition, and you see a university with strict cost controls: 14 full time faculty and over 160 adjuncts and absolutely modest facilities. Its mission is “To fulfill the ever growing demand for employable human capital in various industries through continuous interaction with” etc., focusing on “tailor made programmes whilst equipping this human capital with cutting edge skills knowledge and information.” If offers doctoral programs in business, but “Other areas of specialization can be given consideration by the University Senate.” Its campus is spartan (the library had one shelf of business books, mostly texts, and two of law; the classrooms have whiteboards but no visible technology) but has almost 5000 students, mostly from Zambia and Zimbabwe. The University borrowed $200,000 to build the current campus, which it paid off in two years, a mark again of its efficiency.

As I said, it seems to fill a need in a country where—and I haven’t said this earlier—those living under the poverty line comprise 60% of the population.

On to Johannesburg.

Lusaka

We’re back to work….

How many of you thought of taking a vacation in Lusaka, Zambia?

I thought so. If you did, I would have been surprised, because this city of 4 million inhabitants —about 7 hours and 250 miles by bus from Victoria Falls, is better recognized (about a third of the population—and they were on the street to greet us in their cars at 1:30 when we arrived—or so it seemed) as the business and political capital of Zambia. That’s why we’re here—to resume our quest for knowledge about doing business in sub-Sahara Africa.

The British moved the political center here from Livingstone in 1935 to be close to the copper mines. I should point out that there are some safaris nearby, and camping as well (it’s a big country relatively sparsely settled); the economic officer of the embassy, who helped arrange many of our visits, noted he prefers this station to his previous posts—Beijing, Hanoi, and Cape Town—partly because of the less frenetic pace here. He regaled our table at lunch with his camping experiences—from having the attendants at the park (they are basically water bearers) cut a ten foot branch, bring it down, and slay the poisonous snake on it. The snake is both aggressive and territorial, and deadly, bad combinations of traits; or the time a pride of 9 lionesses dropped in one day. And we think raccoons are annoying!

Anyway, you can probably tell why you might not want to come to Lusaka, unless you want to do business in this country. Today’s headline screamed “Zambia’s economy thriving—experts,” and while we’re not quoted in the article, from what we’ve seen and heard, there’s reason for the optimism. Some of the optimism comes from the relative political stability, and stabilizing of the local currency (which depreciated about 15% last year); part comes from the natural resources—copper is king here, and we’ll be visiting a company tomorrow; part from the agricultural potential. It has the highest percentage of undeveloped arable land on the continent, and 40% of the available surface water in the region. Hence the potential for hydroelectric power to replace the non-sustainable charcoal, which accounts for 80% of the heating/cooking/pollution/deforestation.

The embassy staff hosted us last night, and noted some of the other economic problems, especially the fact that this is a landlocked country that does not have easy access to the sea. The roads are ok, but the overall rating of logistics is 178th out of 181 countries, with containers costing about six times more than in the United States. The Chinese helped build a railroad to Mozambique, but it apparently collapsed during the rainy season.

We might have peered into the future last night, because after the embassy briefing, the embassy and FDIB hosted a session with the American Chamber of Commerce. The cards I collected included someone from the department of Tourism, a Lebanese print shop owner who’d been here for 16 years, a Dane and a Norwegian working on advanced degrees and interning with the Standard Bank, and the Executive Director of the Chamber, a 30 year old graduate of the University of Dayton who saw the job advertised, and came out; he told me if I had students who want to intern to be sure to contact him.

The highlight was the Minister of Commerce, an exceptionally articulate woman who had been managing director of one of the banks. I thought: “This woman should be president.” When I shared that thought with one of the chamber members, he replied: “That’s why she was put in the cabinet. They want to fast track her.”

Today’s visits included a $300 million agribusiness company, whose goal is to “feed the nation” (and eventually the continent). We went to  their dairy farm, which is a small part of the business, but with two of our faculty from Wisconsin, and the importance of agriculture, a nice visit for us. We donned white coats, hairnets, and galoshes to go to the dairy, a feedlot, with a look at some of their consumer products (they make a yummy hazelnut yoghurt), and a discussion of free range and non gmo meat. Stock feed, beef, edible oils, and crops account for about 15% of the income each. The company lost money last year because of exchange rates and the decline of the local currency. It started 25 years ago and now has a major partnership with Shoprite. The agricultural outlook here prompted Cargill to purchase a $30 million operation.

their dairy farm, which is a small part of the business, but with two of our faculty from Wisconsin, and the importance of agriculture, a nice visit for us. We donned white coats, hairnets, and galoshes to go to the dairy, a feedlot, with a look at some of their consumer products (they make a yummy hazelnut yoghurt), and a discussion of free range and non gmo meat. Stock feed, beef, edible oils, and crops account for about 15% of the income each. The company lost money last year because of exchange rates and the decline of the local currency. It started 25 years ago and now has a major partnership with Shoprite. The agricultural outlook here prompted Cargill to purchase a $30 million operation.

The other visit was to a Chinese Special Economic Zone. In 2006, Hu Jintao said China would open 3 in Africa, and the one here is just getting off the ground. We went into an exhibition hall which hosts Chinese who want to sell and Zambians who want to sell or buy, too. The red banner celebrating “Motherland in heart, mobilize our love for Africa to win hand-in-hand,” reminded me of similar slogans in China to stimulate production and pride. By the end of last year the Chinese claimed to have spent $151 million on infrastructure improvements (it’s near the airport) and attracted $1.2 billion in Chinese investment, primarily from Northeast China’s Jilin province (Changchun is the capital city, and the managing director beamed when I told him, in Chinese, of course, that I had been there). While most of the businesses are in nonferrous metals industry, we toured a mushroom-growing (indoor) farm. We got quite an education on mushrooms (including the numerous health benefits; I think I heard the same type of talk visiting tea farms in Fujian years ago), and the many varieties, including the “oak mushroom,” more commonly known in the West as “shitake” (the manager didn’t seem happy that the Japanese had rebranded it successfully); and several varieties of oyster including a golden one, named for the scientist who took the wild variety and domesticated it.

The other visit was to a Chinese Special Economic Zone. In 2006, Hu Jintao said China would open 3 in Africa, and the one here is just getting off the ground. We went into an exhibition hall which hosts Chinese who want to sell and Zambians who want to sell or buy, too. The red banner celebrating “Motherland in heart, mobilize our love for Africa to win hand-in-hand,” reminded me of similar slogans in China to stimulate production and pride. By the end of last year the Chinese claimed to have spent $151 million on infrastructure improvements (it’s near the airport) and attracted $1.2 billion in Chinese investment, primarily from Northeast China’s Jilin province (Changchun is the capital city, and the managing director beamed when I told him, in Chinese, of course, that I had been there). While most of the businesses are in nonferrous metals industry, we toured a mushroom-growing (indoor) farm. We got quite an education on mushrooms (including the numerous health benefits; I think I heard the same type of talk visiting tea farms in Fujian years ago), and the many varieties, including the “oak mushroom,” more commonly known in the West as “shitake” (the manager didn’t seem happy that the Japanese had rebranded it successfully); and several varieties of oyster including a golden one, named for the scientist who took the wild variety and domesticated it.

One room provided a real education; Zambians were in it using a knife to pare down the large mushrooms for sale. While the company at this point is still selling only locally, I had visions of something I had said half in jest when my international business class discussed the rising cost of Chinese wages—“There’s always Africa.” The special economic zone claims to have created 8,000 jobs.

One room provided a real education; Zambians were in it using a knife to pare down the large mushrooms for sale. While the company at this point is still selling only locally, I had visions of something I had said half in jest when my international business class discussed the rising cost of Chinese wages—“There’s always Africa.” The special economic zone claims to have created 8,000 jobs.

We saw a number of Chinese language hotels and restaurants in the city, which indicates to me the presence of a substantial Chinese population of traders and businessmen. I shouldn’t complain, though. We’re staying at a Taj Hotel (probably because of the Indian traders and businessmen), and as a result, I had freshly-cooked dosa, paneer, and sambal for breakfast. It was a very welcome change (to me) from American and British breakfasts that have been standard fare for the last three weeks since I left the US.

Bon appetit!

2 days, 3 countries, 5 passport stamps

Victoria Falls

We’re in tourist Africa, again—this time at a resort overlooking a world-class tourist site—Victoria Falls. While names of other landmarks and towns have changed (I’ve finally figured out the pre-independence names), Victoria Falls, named in the 1850s by David Livingstone, a medical missionary who spent most of his life “discovering” Africa, is still named for Her British Majesty, and Livingstone, the city, still bears the name of the explorer.

Getting here yesterday involved two of the three countries. We left Botswana (originally the Bechuanaland Protectorate) after another game drive. We went back to the site of the elephant-lion encounter (though I’m not sure that the lions killed the elephant), and the lions were still there. I hope l have a picture of a lioness surveying the crowd who’d come to watch, her whole mouth red—like a little kid who’d eaten Thanksgiving dinner without a fork (which is actually how lions eat!). It was a quiet drive, but at the end, most of the animals we saw came to say good-bye.

We had a briefing last night by one of the faculty tour leaders, who told us some interesting things about the two million citizens of Botswana—from independence until the mid 90s, it had the fastest growth rate in the world. The secret? Diamonds. They may be, as Marilyn Monroe crooned, “A girl’s best friend,” but they’re definitely Botswana’s. The country has an agreement with DeBeers, that gives the country 70% of the diamond revenue. The current GDP per capita, at $14,000, is one of the highest in the region; only South Africa, which, it turns out, owns many of the industries here, is higher.

While we were waiting at the border (the Zambesi River) between Botswana and Zambia (nee Northern Rhodesia) for the one passenger ferry to take us and our bags across the river, we came upon a monument that told us a lot about the politics here: the monument dedicated a bridge in September 2014. The bridge has been delayed because of the politics—Botswana isn’t eager for it because most of the traffic is Zambia-South Africa. As I mentioned, the delays can be up to a week.

That brought us to Zambia, where we’ll be until early Friday morning when we return to South Africa. The former Northern Rhodesia, with about 14 million people has an income around $4500 per capita, based partly on tourism, partly on the copper mines in the north. I’ve said tourism is the world’s biggest business, and Victoria Falls certainly is spectacular. One mile wide, it’s the waterfall with the largest volume of water, and I confess I was not expecting the thunderous cascades. Seeing the whole thing required the next country, a visa, and a $30 fee to enter the park.

The country is Zimbabwe, formerly Southern Rhodesia, a country with a checkered and violent history, that probably started when the white racist Ian Smith declared independence from Great Britain and promised white supremacy for a thousand years (didn’t Hitler do that, too?). Anyway, most of us walked across the 1905 bridge that defines the border here, and spans one of the deepest gorges in the world. During the summer (remember it’s winter here), much of the Zambia side of the waterfall becomes a trickle, and the major cascades are in Zimbabwe. The day was spectacularly blue, which meant a lot of rainbows from the spray.

One option on the Zimbabwe side was to visit an old colonial hotel, an option I readily exercised. The Victoria Falls Hotel, built a century ago, is one of those elegant European hotels that dot the former colonial world. It was built by the Rhodesian railway company, and had probably priceless artifacts. In the main entrance stands 8 foot portraits of King George V and Queen Mary, with British cartoons (a nice series lampooning the British, as the British are wont to do), with maps and pictures from the old days. One interesting fact: the Hotel was on the route of a flying clipper that made the journey from Southampton to Cape Town—in 7 days. The hotel was one of the stops (I suspect it stayed overnight at each of the stops). Withall, the 3 mile traipse across the bridge yielded some spectacular pictures.

One option on the Zimbabwe side was to visit an old colonial hotel, an option I readily exercised. The Victoria Falls Hotel, built a century ago, is one of those elegant European hotels that dot the former colonial world. It was built by the Rhodesian railway company, and had probably priceless artifacts. In the main entrance stands 8 foot portraits of King George V and Queen Mary, with British cartoons (a nice series lampooning the British, as the British are wont to do), with maps and pictures from the old days. One interesting fact: the Hotel was on the route of a flying clipper that made the journey from Southampton to Cape Town—in 7 days. The hotel was one of the stops (I suspect it stayed overnight at each of the stops). Withall, the 3 mile traipse across the bridge yielded some spectacular pictures.

Today is African independence day, which seems to be a holiday celebrated throughout much of the continent. We had the day free, especially in the morning—and there were a plethora of activities to (pay for and) choose from. I think two of our faculty took the microflight trip over the falls, and a few toured the city of Livingstone, which has one of the best ethnography museums in Africa, but most went to animal farms where they could walk with lions, cheetahs, or elephants.

I chose to take what was supposed to be a canoe trip on the Zambezi River which turned out to be a two man kayak; I went with the youngest member of our group, and we were in the front of the kayak, with a guide in the rear. I envisioned a narrow river, with trees along the banks, and snakes hanging from them jumping into the boat. Instead, we did a five-mile stretch, with a National Park on the Zimbabwe side and a sparsely-settled Zambian side—and the river is probably a quarter of a mile wide. The best part for me—besides the fact that there was no traffic other than our two boats—was an island we passed that had a hippo that surfaced, blew out air and water, and snorted, that and the crocodiles we spotted on the banks.

I was thinking that I had become Scoutmaster about 32 years ago, and what a wonderful way to celebrate that achievement, if 9000 miles from Troop 19.

We leave at 6 am tomorrow for a 6 hour bus ride to Lukasa, the capital of Zambia. Good night!

The Lion Sleeps Tonight

Some of you are old enough to remember Pete Seger and the Weavers. I know I am. I remember seeing them sing at the old Roosevelt Auditorium at a benefit hosted by Studs Terkel for the striking coal miners in Kentucky. I remember telling Carolyn, “Half the audience is FBI,” because both Seger and the Weavers were on the list of suspected Communist sympathizers in the 1960s because they sang about social justice.

One of their songs, “Wimoweh,” haunts me today, because it purports to be a song about Africa—“The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” Well, I know at least one lion who will be sleeping well tonight, or certainly well fed, because on our  morning game drive in Chobe National Park we came upon an unusual sight—3 lionesses and 2 cubs feasting on a downed elephant. By the time we got there, the real delicacy, the trunk, was gone, and mom and two cubs were tearing at the carcass. I was a little surprised that with all the impalas in the park (and we saw lots of them and other animals) the lions had gone after an elephant. I suppose that proves who is really king of the jungle. As I said, the park borders the river, and thus offers a little different animal environment than the drier environs I saw at Sabi-Sabi, which is almost south of here. I’m sure those lions will sleep well tonight, or at least well-fed. We’ll be back in the morning to see whether the scavengers in the food chain—the hyenas, jackals, and vultures—will be there, or whether the lions will still be feeding.

morning game drive in Chobe National Park we came upon an unusual sight—3 lionesses and 2 cubs feasting on a downed elephant. By the time we got there, the real delicacy, the trunk, was gone, and mom and two cubs were tearing at the carcass. I was a little surprised that with all the impalas in the park (and we saw lots of them and other animals) the lions had gone after an elephant. I suppose that proves who is really king of the jungle. As I said, the park borders the river, and thus offers a little different animal environment than the drier environs I saw at Sabi-Sabi, which is almost south of here. I’m sure those lions will sleep well tonight, or at least well-fed. We’ll be back in the morning to see whether the scavengers in the food chain—the hyenas, jackals, and vultures—will be there, or whether the lions will still be feeding.

Ironically, our dinner speaker was a woman who heads a Non Government Organization called Elephants Without Borders, which has gotten a grant from Paul Allen (a Microsoft founder) to survey the animal population in Africa. While much of our discussion focused on poaching, the real problem for animals in Africa involves habitat fragmentation. These are animals that need room to roam, and she noted we’ve closed off many of their routes. In other words, as I suggested to her, the problem is not wildlife management, but people management. As the lions discovered this morning, they did help solve any surplus elephant population for a long time.

This morning, a number of us crossed the Chobe River into Namibia (which I knew sort of from philately as German Southwest Africa), making country number 4 that I’ve visited in southern Africa. Our goal was to visit a local village, and to get there, we had to migrate out of Botswana, take a ferry into Namibia, then go through customs/immigration to get to the village which is on an island. According to our guide, about 2,000 people live on the island, which is bereft of electricity, water, and sanitation (“we use the bush,” said the guide; “only old people use latrines,” he told us). There were 48 villages on the island; ours was named Kubufu, which means “maize,” which grew on the island. At one time, the story goes, there were also lots of black mambas on the island, a deadly snake, but when the villagers dispatched them, they killed a python as well, and put that above the village because the python is the king of snakes, and warns others away. You better believe I kept an eye peeled on the road.

We visited one house, which belonged to the village chief, who near as I can tell, controls the village. His permission had to be given to build the immigration point—a relatively modern building that has a modern toilet, as I found out.

Most houses were built of mud, with the final layer hand smoothed termite soil, which is very durable (hope the termites don’t make the journey), fashioned around a wooden frame structure. If you want to get married (I already am), you tell your uncle or grandfather, who work out the arrangements, which includes building a house. The house consists of a tall reed fence, which assures some privacy, a one room house for you, with curtains to partition off some rooms, another one room house for guests or children over 7, and a kitchen. The chief’s house was rather attractive, with an unclosed dining area, an outdoor kitchen (cooking is over charcoal or fire), and some solar-generated electricity. All shopping is done across the river in Kasane, the town we’re in.

I chose to take the river safari again in the evening, rather than jouncing overland in the Land Cruisers here. It was a good choice in terms of what we saw, because Botswana has 125,000 elephants, the largest number in the world, and most of them were down by the river—there was one herd of probably 30, and it was great to be close enough to see them wading,  drinking, and throwing sand on themselves. The little ones seemed almost out of Disney cartoons, and I swear one said, “I can fly,” but bear in mind the cruise served adult beverages. There were also crocodiles on the banks, including a 4 meter one with its mouth open (that’s how the animal

drinking, and throwing sand on themselves. The little ones seemed almost out of Disney cartoons, and I swear one said, “I can fly,” but bear in mind the cruise served adult beverages. There were also crocodiles on the banks, including a 4 meter one with its mouth open (that’s how the animal  controls temperature), which made for some great pictures.

controls temperature), which made for some great pictures.

One of the options our tour director’s wife exercised (partly because she had been here before) was to go on a photo safari. It was pricey, but I might have done it had I known. She did an instructional class, a game drive on land, and then a safari cruise. They lent her a camera and lens combination that carried physical education credit—it was a 100-500 mm lens, which needed a tripod. The boat they used had around ten photographers with their mounted cameras looking for all the world like some gunboat out of a bad scout skit, but the pictures I saw were truly professional looking. If ever you come here, at least remember to bring a good camera with a good lens; cell phones won’t do it.

Well, the lion will sleep tonight, and from all I’ve done today, I suspect I will too.

“Wimoweh, wimoweh, wimoweh.”

Hi from Botswana

Tourist Africa: Chobe Botswana

We’re almost 1200 miles from Cape Town and 17 degrees closer to the equator tonight. Getting here required leaving Cape on a 7:30 am flight for Johannesburg, then a flight to Livingstone (named for David Livingstone, I presume), the onetime capital of Zambia, now one with a major (Chinese built) airport, and roads into the interior (again Chinese built), that took us through 3 countries/customs, and across the Zambezi River at a point where it defines four countries: Zambia, Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. If that sounds confusing, you should have seen the traffic waiting to cross the river—by ferry. We got fast tracked, but the trucks were lined up and wait anywhere from three days to a week to go across. We took a speedboat to get across, and so did our baggage.

What an insight into logistics nightmares! Makes you wonder about what was really happening at that checkpoint, and grateful for the transportation system in the United States. I met an Indiana Hoosier in Cape Town who had motorcycled with a group from Cairo to the Cape, and he said it took about a month, but was mostly on roads, mostly paved. He did mention a few stretches which required armed guard escorts.

As for us, we’re back in tourist Africa, at a lodge that is also a marina. What that means is that we’re on the Chobe River (one of the Zambezi tributaries), at the entrance to a National Park, with wetlands that look like the Canadian Wilderness near Bissett, but with the significant difference in the animals, naturally. We did a dinner cruise when we got here, and saw, in habitat: giraffes, buffalo, crocodiles, elephants, hippopotami, and the ever useful impala. Not to mention a stunning sunset and a sky that is full of stars you probably can’t see at home—and I finally discovered where Orion hides during the summer. We’re doing a land safari tomorrow morning (6-9 am), and we’ll have a choice whether to do another cruise or another land safari tomorrow afternoon. Sunday we’ll be visiting Victoria Falls before resuming our business visits in Lusaka, the capital of Botswana.

As for us, we’re back in tourist Africa, at a lodge that is also a marina. What that means is that we’re on the Chobe River (one of the Zambezi tributaries), at the entrance to a National Park, with wetlands that look like the Canadian Wilderness near Bissett, but with the significant difference in the animals, naturally. We did a dinner cruise when we got here, and saw, in habitat: giraffes, buffalo, crocodiles, elephants, hippopotami, and the ever useful impala. Not to mention a stunning sunset and a sky that is full of stars you probably can’t see at home—and I finally discovered where Orion hides during the summer. We’re doing a land safari tomorrow morning (6-9 am), and we’ll have a choice whether to do another cruise or another land safari tomorrow afternoon. Sunday we’ll be visiting Victoria Falls before resuming our business visits in Lusaka, the capital of Botswana.

I may actually get to finish “Nature Merit Badge” before we leave.

Have a great holiday.

A last look at the cape

We’re leaving Cape Town in the morning for “Africa.” I’m sure it will be a shock to leave this first world ambience, which characterizes most of the Cape Town area we explored yesterday (the Consulate is in a swank neighborhood) and along the coast today. We did the “Cape tour” which took us around the Cape of Good Hope (baptized originally, as I mentioned, as the Cape of Storms by discoverer Diaz, but renamed “Good Hope” by a shrewder King). The highlights are probably best captured in pictures (which I’ll send when I get a chance), but here’s my attempt to verbalize them:

The ride around the Cape peninsula is a study in wealth expressed primarily in architecture—beautiful homes fronting the Atlantic, in towns like Simon’s Town (the headquarters of the British South Atlantic Fleet until 1957, and a naval base today); a “cheap home” cost around $500,000. The area has attracted a lot of Europeans because of the low relative price for the high relative value—gorgeous scenery.

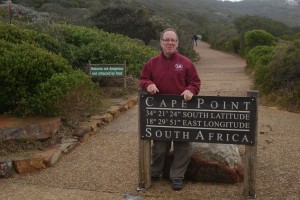

The stop at the Cape itself. Though it’s not where the two oceans (Indian and Atlantic) meet, the Cape is where most people think they meet (it’s at another cape not more than 100 meters away). The setting is stunning, with beautiful beaches and cliffs—and about a mile and a half hike for the adventurous (including me) from one of the beaches to the aptly named “Two Oceans Restaurant,” which served some delicious seafood. I enjoyed the Cape Lobster, partly because someone told me it was less than an hour off the boat.

We also had another stop at a penguin colony, in a nicer setting than Betty Bay, where I had been greeted by my little friends in tuxedos. This stop, part of the Table Mountain Marine Reserve, started with two pairs in 1982, and with encouragement (numbered fiberglass burrows), some food supplements, and changes in legislation and attitude in favor of environment, the colony is up to 2000. I wish I could swim as well as they do—about 5 miles an hour—but they look really graceful in search of food. Tis said they will feed within 6 miles of the colony.

We also had another stop at a penguin colony, in a nicer setting than Betty Bay, where I had been greeted by my little friends in tuxedos. This stop, part of the Table Mountain Marine Reserve, started with two pairs in 1982, and with encouragement (numbered fiberglass burrows), some food supplements, and changes in legislation and attitude in favor of environment, the colony is up to 2000. I wish I could swim as well as they do—about 5 miles an hour—but they look really graceful in search of food. Tis said they will feed within 6 miles of the colony.

Finally, I did a little exploration of Simon’s Town. There are some old buildings and a cute waterfront that is renovated. There was one marker I hadn’t seen before though—a monument to the diverse peoples of Simon’s Town who lived together in peace until 1967. We weren’t there long enough to piece everything together (there’s a 1923 mosque in the town), but I suspect that during apartheid, the non-whites were forcibly evicted—a sad reminder of the history that still haunts South Africa.

We leave at 4 am for Zambia, in what I am sure will not be a “third world country in a first world setting,” as Consul General/Ambassador Taylor described Cape Town yesterday.

Goodnight. Get ready for a Memorial Day weekend.

Hope at the Cape of Good Hope

Today’s visits capped our business visits in Cape Town, and added to our knowledge of the Republic of South Africa. It’s a port, and has been a port since the beginning in the 17th century, so it was fitting that we visited the Port authority. Actually, South Africa has six or seven ports, the biggest being Durban on the east coast. The Port Authority is a state-owned enterprise that runs the intermodal features that brings containers to and from South Africa; it’s an important industry because logistics is the second largest industry in Western Cape—behind tourism. It’s a major cog in job development (one of the real challenges in South Africa, where unemployment is probably 40% or more), because each container creates six jobs. The major customers are Chinese (wine is increasingly important in the China trade as the Chinese become more middle class) and the rest of Africa, with food processing accounting for 39% of the exports; the leading importers are from China, Europe, and the United States. Interestingly, one of the big suppliers is Caterpillar, which is not surprising given the importance of mining (important in the northeast more than here in Cape Town). One of the bad jokes that circulated was that anyone who complained about the ports committed a port whine.

Today’s visits capped our business visits in Cape Town, and added to our knowledge of the Republic of South Africa. It’s a port, and has been a port since the beginning in the 17th century, so it was fitting that we visited the Port authority. Actually, South Africa has six or seven ports, the biggest being Durban on the east coast. The Port Authority is a state-owned enterprise that runs the intermodal features that brings containers to and from South Africa; it’s an important industry because logistics is the second largest industry in Western Cape—behind tourism. It’s a major cog in job development (one of the real challenges in South Africa, where unemployment is probably 40% or more), because each container creates six jobs. The major customers are Chinese (wine is increasingly important in the China trade as the Chinese become more middle class) and the rest of Africa, with food processing accounting for 39% of the exports; the leading importers are from China, Europe, and the United States. Interestingly, one of the big suppliers is Caterpillar, which is not surprising given the importance of mining (important in the northeast more than here in Cape Town). One of the bad jokes that circulated was that anyone who complained about the ports committed a port whine.

Cape Town is economically and racially different from the rest of South Africa. While the average income is $11,000, that figure is skewed; as I mentioned unemployment is high, probably higher than the official 25%; youth under 24 are estimated to run 65% unemployed. Racially, the country is roughly 80% black, 10% white ( 70% Afrikaan, 30% English), 9% coloured, and 2% Asian, but in Western Cape it is roughly 15% black, 33% white, 41% coloured, and 3.5% Asian). You can see from these statistics that the country ranks as one of the world’s worst in terms of income inequality. Before the democratic elections in 1994 (remember this is a 21 year old country; it’s the US in 1797, suggested one of our speakers), only 2% of the wealth was controlled by blacks. The government has made it a point to raise that to 26%, and has in place a system of rewards (and punishments) to push black enterprise, similar to what happened as I mentioned in Malaysia.

In addition to job creation and income redistribution, the major challenge economically facing the government has been an energy crisis. Capacity is still where it was in 1998; through bad planning, mismanagement, lack of maintenance, there are rolling blackouts. I’ve experienced a few, but the hotels I’ve stayed at have had backup generators, happily; otherwise, we’d be in darkness for 2 ½ hours.

I stated that we had two visits that were primarily about China—at both our universities—and there is no doubt that China has been making its presence known in Asia, to the point where 50% of Africa’s trade is with China (though only 5% of China’s). The reasons are pretty clear: China wants political allies (there were strong Maoist influences in the African National Congress’ struggle against apartheid); China has the pricing power to supply poor countries with cheap goods; China’s infrastructure companies have slowed work at home and are available to sell elsewhere; and China’s enormous growth has consumed enormous quantities of commodities which Africa has in abundance. The Chinese have come into a number of countries and built dams, universities, roads, power stations, etc., and the geopolitical/business issues have prompted a lot of articles in the business press.

We discussed the issue with the US Consulate General here in Cape Town (his last posting was as ambassador to Papua New Guinea, so he had some Asian exposure to the Chinese trade diplomacy), and his point was that the Chinese can build roads, but don’t create jobs, while American initiatives like the AGOA (an act fostering African-US trade), the funding ($4.8 billion over the decade) to combat AIDS, and the Yali program (young African leadership initiative),which brings 500 African leaders (25-35) to the United States for 5-6 weeks of interchange with each other and government officials has been more productive of having longer-term effects than, as one faculty member put it, building a road with road stands where farmers can sell oranges.

One of the Yali graduates founded a business I went to today, RLabs, which may provide answers to some of the serious problems I outlined—60% youth unemployment, high crime rates, essentially a response to a government that has failed, schooling has failed, and the family has failed (South Africa has the highest HIV rate in the world, though the US aid has brought it down quite a bit). RLabs reminded me of Hull House in Chicago, which at the turn of the last century, brought immigrants in and educated them and gave them hope. This is what RLabs has done with and for local young people; we saw a change behavior modification class, a youth café, and efforts to work with—partner is the word– business and governments (US AID, the Finnish Government are two of the sponsors); they run a leadership academy, and a social enterprise incubator. And I thought, “Here may be the way out,” and as I’ve told students for years, “Without business, there’s no solutions.” It was a great look at a “missionary organization” whose graduates we met and expect to see in positions to make a difference in their world—and ours.

Some thoughts on Africa

If you’ve ever felt that going to school was like being in prison, you ought to consider going to the Graduate School of Business at the University of Cape Town, as we did. It’s right next door, a few miles from the main campus, which has been in the news for the protests that took down the statue of its founder—Cecil Rhodes, English colonialist par excellence (Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, was named for him). Point is, the GSB is in a former prison (they have a marketing class called “Cells 101” I’ll bet!), which houses the school, and a hotel. The classroom we were in had a chalkboard (I wondered what I’d be able to do with the chalk I’ve pilfered over the years) and was named for “Old Mutual,” one of the leading local insurance companies, which we discovered, has funded rooms on other campuses in the Western Cape, the province that includes Cape Town.

If you’ve ever felt that going to school was like being in prison, you ought to consider going to the Graduate School of Business at the University of Cape Town, as we did. It’s right next door, a few miles from the main campus, which has been in the news for the protests that took down the statue of its founder—Cecil Rhodes, English colonialist par excellence (Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, was named for him). Point is, the GSB is in a former prison (they have a marketing class called “Cells 101” I’ll bet!), which houses the school, and a hotel. The classroom we were in had a chalkboard (I wondered what I’d be able to do with the chalk I’ve pilfered over the years) and was named for “Old Mutual,” one of the leading local insurance companies, which we discovered, has funded rooms on other campuses in the Western Cape, the province that includes Cape Town.

We’ve spent the past two days with an interesting combination of business and academic visits, along with limited touring. Here’s some of the things I’ve learnt (this is a former British Colony, after all), starting with the Continent.

Africa is a continent, not a country. In fact, there are currently 54 countries in Africa, and one of my devious teaching tactics is to give students a map of Africa with the country outlines and a list of the names of the countries to match. More than ten is unusual. The divisions are more pronounced than the similarities. Based simply on the colonial past, the language groups are not a help; West Africa is predominantly French speaking, South and East is English, north is Arabic, with smatterings around the continent of Portuguese and Spanish, and Ethiopian, which is none of the above. Religious differences abound, even within some countries; Northern Nigeria (the biggest economy and with 170 million people, the largest country) has Muslims in the north and Christians in the South, similar to the Sudan. The current countries make as little sense as do some of the boundaries in Europe, with tribal underlays (11 official languages in South Africa alone).

It does not seem, either, from our speakers, that there is a sense of “Africanness” on the continent, unlike, say, China (I’ll have more to say about Chinese-African relations, which has so far been the focus of two of our speakers), where despite regional differences and dialects so different that they’d be languages in Europe, there is a sense of being Chinese. It’s hampered cooperation, which is probably economically essential. One of the books I read pointed out that one reason for the lack of business interest in Africa—despite the fact that in many ways it is easier to do business here than in Asia—is that the payoff with 1 billion Asian customers is higher than the individual 54 countries.

As for South Africa, we’re getting a feel especially for the Cape Town area, the Western Cape. Like many countries, it’s a product of its history, beginning with the Dutch, whose racial attitudes have stamped the country to this day. It’s ironic to me that in the 1960s, when the civil rights movement in the United States began to break down our version of apartheid, South Africa clamped down on its Blacks in ways that made South Africa a pariah. Not until the early 1990s did democracy come to South Africa, a movement that created what was then called a “rainbow nation” with four races—Black, Coloured, Asian, and White—partly a product of the British background, which brought in laborers (slavery was abolished in the empire in the 1830s, I believe) from other countries to work in the colony. As in Malaysia, where similar mixing happened, the Mandela government tried to redress the economic imbalance in particular (and the upper class is increasingly mixed), a thrust that has kept it in power despite the obvious problems the current regime has (President Zuma has 4 wives, 20 children, and spent several million dollars the country can ill afford to spend on his house). The party of liberation is kept in power partly because of its history—and close ties with the labor unions that give it about 70% of the vote and power in 8 of 9 provinces. It’s rival, we’re told, is in opposition, but without power of its own. The strength of labor has hamstrung some economic moves, as it has in Europe, and as I mentioned, one consequence was the move of some businesses to lower cost countries in Africa.

history, beginning with the Dutch, whose racial attitudes have stamped the country to this day. It’s ironic to me that in the 1960s, when the civil rights movement in the United States began to break down our version of apartheid, South Africa clamped down on its Blacks in ways that made South Africa a pariah. Not until the early 1990s did democracy come to South Africa, a movement that created what was then called a “rainbow nation” with four races—Black, Coloured, Asian, and White—partly a product of the British background, which brought in laborers (slavery was abolished in the empire in the 1830s, I believe) from other countries to work in the colony. As in Malaysia, where similar mixing happened, the Mandela government tried to redress the economic imbalance in particular (and the upper class is increasingly mixed), a thrust that has kept it in power despite the obvious problems the current regime has (President Zuma has 4 wives, 20 children, and spent several million dollars the country can ill afford to spend on his house). The party of liberation is kept in power partly because of its history—and close ties with the labor unions that give it about 70% of the vote and power in 8 of 9 provinces. It’s rival, we’re told, is in opposition, but without power of its own. The strength of labor has hamstrung some economic moves, as it has in Europe, and as I mentioned, one consequence was the move of some businesses to lower cost countries in Africa.

The country is big, partly (again) a function of its history. Cape Town centered on its ability to reprovision ships sailing around the Cape (we went back again to Stellenbosch, the second city founded in the Cape, and I’d love to wander around the Cape Dutch architecture; the  basis is agriculture and vineyards). Discoveries of gold and diamonds prompted the settlement of Johannesburg, which is still the financial capital of the country and home to over 50% of the some 48000 millionaires in South Africa. It’s 1000 miles away. As a result of the Boer War (the Dutch uprising to avoid British rule, as I mentioned, a brutal guerilla war that lasted about four years), the government even today splits time: the Parliament meets six months here and six months in Joburg, with administrative and judicial offices also in Bloemfontein.

basis is agriculture and vineyards). Discoveries of gold and diamonds prompted the settlement of Johannesburg, which is still the financial capital of the country and home to over 50% of the some 48000 millionaires in South Africa. It’s 1000 miles away. As a result of the Boer War (the Dutch uprising to avoid British rule, as I mentioned, a brutal guerilla war that lasted about four years), the government even today splits time: the Parliament meets six months here and six months in Joburg, with administrative and judicial offices also in Bloemfontein.

We’re in the Waterfront area, a huge mall restaurant complex that could be in any big city near the ocean. I’ll have more to add I suspect after our visits today—including to the US consulate—and I do want to comment later on the hot topic—China-Africa relations—based in part on our visit to the first Center for Chinese studies (with a focus on Africa).