We left Ulanbataar with a better feeling for it than our original impressions as a combination of Eastern Europe and the kind of city you see from the train as you travel out west. It does have features that resemble both, but it’s only 20 years removed from being a Soviet satellite, and is slowly growing more comfortable with its past (the Soviets wiped out others’ history, and think of the Tartar years–the Mongol occupation– as the low point in Russian history). The airport, for example, is Genghis Khan International, and a $10 million statue of the Great Khan and his offspring decorates the main square of the city.

As I said, it’s a country of 2.7 million people or so, 4 times the size of France, with the Gobi desert in the south, and lots of grassland (and a few mountains) in the north. Its economy rests on its produce—especially the export of meat, wool, and hides to its larger and more prosperous Chinese neighbor, which accounts for about 20% of GDP. The country imports much of its food, especially fruit, but my diet Coke came from Hong Kong (though there is a Coke factory in UB), and our dessert came from Korea. Tourism is also around 20%, with raw materials (gold and copper mines) a growing part of the trade: and the country is attractive for trekking, and horseback riding (but after my experience, which was only two hours, I’m saddle-sore, and know why the Mongols were attracted to their richer neighbors, and feisty when they got inside the Great Wall, or into Europe). Camels were much slower, but, to my mind, provided a better experience!

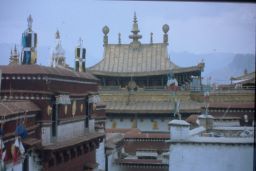

We toured what was left of the past in Ulaanbaatar before we left—apparently, the Mongolians converted to Buddhism in the 17th century, accounting for the relative lack of world conquest since then, and the few monasteries were rebuilt since 1990 or preserved by the Soviet-oriented governments as museums. The Mongolians converted to Yellow Hat Buddhism, the Tibetan variety, and the Lama temple in UB, built at the turn of the last century, houses what the Lonely Planet accurately describes as a cultural gem. The Winter Palace of the Bogd Khan, the political/spiritual ruler of the Mongolian state that broke away from China in 1911, also remains. The Chinese government helped restore it, and, like the Thai palace, it contains European-style buildings—albeit on the Russian style, and artifacts from the Bogd Khan’s years. When he died in 1924, the revolutionaries who had seized power in 1921, dissolved the Khannate and established the communist government that lasted until the Empire fell.

In line with our desire to eat “Mongolian,” we insisted on a boodog, which is an animal (the best is a marmot, but this is the wrong season) cooked from within and without. The Lonely Planet described it as a “balloon with paws,” cooked with a blowtorch, but our mutton cooked with heated rocks in its skin was one of the tastier memories of the trip.

We watched the news in UB before we left; the hotel had a surprising number of stations, including CNN, when we realized that the date was June 4—the 20 year anniversary of the Tiananmen Square suppression. The coverage of the topic was pretty extensive, but I knew we’d not see it in China, and there’d probably be little in the press, and a lot of undercover police on the square, if it were not entirely closed to the people.

My first trip to China, in 1990, was in early June, and our visit to the Square was to coincide with the first anniversary—no one was allowed that day, and very few were there on June 5, when we got there, unfurled our “Long live the friendship of the U.S. and China” banner; the few were armed People’s Liberation Army soldiers, who told us to take our pictures, furl that banner, and get out of there as quickly as possible. We did!

CNN went blank in our TV in Beijing, and I knew what that meant. The government can still censor press, news, and video. The headline 5 June in Global Times, an English language paper in Beijing, was a “news” article about peace and prosperity on Chang’an (the street where Tiananmen Square is located). The article pointed out that in the last 20 years the government has developed a successful model of growth and stability that will provide a model for other developing nations. Again, the article highlights the importance of the intertwining of political stability (party rule) and economic growth.

I bade farewell to JR early in the morning—he had an earlier flight than I did and I sure enjoy traveling with him—and I set out to do some things I’d not done before in Beijing. My goal was to find what was left of Khanbaliq, the capital that Kublai Khan built as the capital of the Yuan dynasty. Not much is left, but the trip through Beihai park, which was one of the imperial gardens from the 12th century until the fall of the dynasty in 1911, was a reminder that in the parks, as the song goes, “Every day’s the fourth of July,” or in the Chinese case, probably October 1 (the founding of the PRC) or October 10 (the revolution of 1911) or the New Years. There were no tour groups there, very few foreigners. And lots of folks, doing what Chinese do in the mornings—taiqi, calligraphy, dancing (ever heard the “Red River Valley” in Chinese?) playing cards, singing, exercising. Major buildings, many of them built by the great Qing emperors, Kangxi or Qianlong, reminds one of the wealth of China before its century of humiliation, and how much of it was concentrated in the hands of the royal family, and the Confucian elite. I got to two houses in Houhai, another artificial lake that has become a bar center at night; one of the hutongs had been the home of a famous writer, and shows that even under communism, favored people live better than others, though the wealth of Beijingers, and Chinese in the big cities today, raises questions about whether you’re in a Third World country or not. Beijing certainly has the trappings of a major world capital—with great restaurants (we had a wonderful farewell dinner of Beijing duck—go to Nanxingcang when you’re there!) and a growing consumer base that could lessen China’s dependence on exports. The other was a palace of Prince Gong, a sprawling home/garden that lends credence to Deng Xiaoping’s comment, “To be rich is glorious.”

The plane was miraculously not full, and I had two seats, which helped me think about (albeit very briefly) why I could leave at 4:10 and arrive at O’Hare at 4:30. Too bad it felt like 12 hours!

As always, Chairman Mao’s statement (during the Vietnam War) is a reminder that “Americans are not Asians, and sooner or later they must go home.” I’m glad it was later rather than sooner.

I will see you soon.

e is a

e is a