When I arrived at IWU in 1987, students had to take 35 course units (roughly the equivalent of a regular course elsewhere), except that each course unit equalled 4 hours elsewhere. Each faculty member taught 7 courses. A January term class provided students the opportunity to take at least the three additional courses needed for graduation (they needed 35 total), and could include an international (or domestic) trip in January. The trips were supported by federal loans. Faculty members were required to offer a January term class, which might be international.

January term class, which might be international.

Up until 1994, I had steered my services marketing class into a 3 night stay at the Palmer House (as the students viewed it) or 4 days of site visits (as I viewed it) in Chicago. That trip included a performance by the Chicago Symphony or the Lyric Opera, a discussion with Information Resources Incorporated (an early data-mining company), the marketing director of the Art Institute, etc.

It was obvious to me, however, after my 1990 trip to China, that my “calling” was to take students overseas and share my background expertise and love of adventure with a January term class. What prevented that was that a member of the business department had a lock on the trip, and the chair insisted that (at the time), there could be only one business trip.

Fortunately for me, Dr. Kieh, chair of the (nonexistent) International Studies Department  (nonexistent because it was cobbled together with faculty who had appointments in other departments, but taught an International Studies class), offered me the opportunity to develop a course on Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast for International Studies credit. That was my 1994 segue into teaching a travel course for almost 20 years at IWU. It started in China, but gradually expanded to East and Southeast Asia, to Europe, and in 2001, a trip around the world. Most were in business.

(nonexistent because it was cobbled together with faculty who had appointments in other departments, but taught an International Studies class), offered me the opportunity to develop a course on Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast for International Studies credit. That was my 1994 segue into teaching a travel course for almost 20 years at IWU. It started in China, but gradually expanded to East and Southeast Asia, to Europe, and in 2001, a trip around the world. Most were in business.

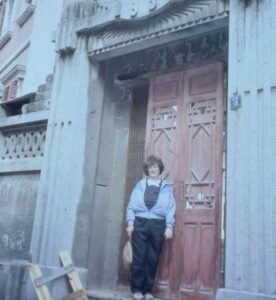

The two memories that stand out the most to me from this trip both involved Xiamen, one of my favorite cities in China. Known as Amoy in earlier days, it had, on the island of Kulangsu, the “other” International Settlement (other than Shanghai) from imperialist days.

The two memories that stand out the most to me from this trip both involved Xiamen, one of my favorite cities in China. Known as Amoy in earlier days, it had, on the island of Kulangsu, the “other” International Settlement (other than Shanghai) from imperialist days.

With no cars, the island was pedestrian friendly, and still full of colonial remnants, including a well-deserved reputation for music. This trip, we managed to stay on the island, in what I thought was a wonderful old hotel, but which was so primitive that I feared I’d have to barricade the doors to keep student protesters out. It didn’t mollify the students that the Wall Street Journal staff was quartered in the same hotel–for them it was a reward!

A funny story afterwards: I called to order the Far Eastern Economic Review (I was teaching an Asia Pacific freshman class at the time), and I got talking with Ms. Li, who worked for the Wall Street Journal Bureau in Beijing. “Oh, you must know Jim Macgregor, head of the Bureau,” I suggested. “How do you know him?” “He headed the only other group at Gulangyu Island when we were there several years ago.” “I was there–wait, I remember your students. They were the ones who whined!” Yes, IWU does have an international reputation!

The second memory was finding a shop that could make the impressive scrolls that hung on so many public meeting sights in China. I commissioned one that celebrated the last January Term and the Weidade Jiaoshou and his xiansheng who were on it. The banner used to hang in my office, and is now safely secured in my apartment.

The second memory was finding a shop that could make the impressive scrolls that hung on so many public meeting sights in China. I commissioned one that celebrated the last January Term and the Weidade Jiaoshou and his xiansheng who were on it. The banner used to hang in my office, and is now safely secured in my apartment.

I think this was also the year we stayed at the Palace Hotel in Shanghai, across from the more famous Sassoon House (now the Peace Hotel).

I think this was also the year we stayed at the Palace Hotel in Shanghai, across from the more famous Sassoon House (now the Peace Hotel).

I believe it snowed in Shanghai this trip or the previous one, and a visit to Fudan University (the IWU of China, as was Yenching in Beijing) furnished my lesson to business students for several years. China was energy poor, and heat was limited south of the Yangtze River. Shanghai was south of the Yangtze, and so the school was unheated. We saw students in their down parkas in a study room, preparing for final exams. In later years, I would point out that their Chinese competitors took studying seriously. As Thomas Friedman pointed out, “They’re hungry for your jobs.”