Turkish Delight: or how I paid homage to Jules Verne

I’ll get to the explanation for the title if you’ll read to the end, but since this is the last day of my adventure, I tried to do a lot.

One thing I wanted to do was “trek” in one of the many valleys here. There  are trails, and I started on one of them when I arrived, but midday heat, and the 5 am departure from Istanbul made that one pretty short. As part of our tour today, I walked a very pleasant 2.5 miles today in a narrow canyon that contained walnut and apricot trees, grape vines—and old stone houses, churches, in the old caves still used for storage and pigeon raising even today. Pigeons get locked in one room for a month (phew!) and get the idea they need to return; their manure is harvested (phew!), though our guide noted that since the area became a UNESCO site in the 1980s, chemical fertilizers had replaced the pigeons to a large degree.

are trails, and I started on one of them when I arrived, but midday heat, and the 5 am departure from Istanbul made that one pretty short. As part of our tour today, I walked a very pleasant 2.5 miles today in a narrow canyon that contained walnut and apricot trees, grape vines—and old stone houses, churches, in the old caves still used for storage and pigeon raising even today. Pigeons get locked in one room for a month (phew!) and get the idea they need to return; their manure is harvested (phew!), though our guide noted that since the area became a UNESCO site in the 1980s, chemical fertilizers had replaced the pigeons to a large degree.

Second, I had a chance to see an old Greek village. There is a poster here  touting the “first declaration of human rights,” a 1463 announcement from Mehmet the Conqueror that his newly-acquired subjects in Bosnia were free to practice their religion. Though it was honored on and off in Ottoman history (people of the Book—as they referred to Jews and Christians—were usually tolerated), but I think paid extra taxes and could not serve in the military. Captured Christian children, however, were frequently raised Muslim, and became the shock troops of the janissaries, the infantry of the Ottomans, but the 20th century relations with Greeks (perhaps beginning with the war for Greek independence in the 1820s), Armenians, and Kurds was and is troubled.

touting the “first declaration of human rights,” a 1463 announcement from Mehmet the Conqueror that his newly-acquired subjects in Bosnia were free to practice their religion. Though it was honored on and off in Ottoman history (people of the Book—as they referred to Jews and Christians—were usually tolerated), but I think paid extra taxes and could not serve in the military. Captured Christian children, however, were frequently raised Muslim, and became the shock troops of the janissaries, the infantry of the Ottomans, but the 20th century relations with Greeks (perhaps beginning with the war for Greek independence in the 1820s), Armenians, and Kurds was and is troubled.

When Turkey was carved (that was the pun in the ’20s) into spheres of influence after World War I (the French, for example, wanted a mandate over the Levant, the area close to Lebanon), the Greek government went to war (backed by the British and the French) to create a protectorate over the Greek cities in Asia Minor, particularly Smyrna. Ataturk mustered Turkish forces to fight for a Turkish state that has the boundaries Turkey now has. There was, however, a massive exchange of Muslim Turks in Greece for Orthodox Greeks in Turkey. One result was the city in the area that still has the abandoned Greek area on a hill. Word is that the Greeks were offered compensation, but have refused, hoping they could return “home” and that was 1923!

Third, I had a chance to test my claustrophobia. There are 36 “underground cities” in the area—which says something about the neighborhood! I expected people to be living in cities underground, but these were, in effect, defensive bunkers. The one we visited had 8 layers that went down about 90 feet, but only two of those were open. Populations (4,000 could be housed in this one; the biggest “city” accommodated 10,000) could simply hide underground when enemies approached. The defensive mechanics were ingenious. Huge stone doors could block entry to a tunnel, but could  only be shut or opened from the inside; air shafts made ventilation possible, and residents could fully function, with a church (the area, as I said, was Christian, even after the Muslim conquest). Tunnels connected everything, and some were pretty narrow, though living quarters were “duplex,” and in any case at least three times the size of a room in London. Many of the tunnels were pretty narrow and not very high—which tested my claustrophobia, but the peek holes where the locals could attack the invaders reminded me of the Viet Cong area called Cu Chi tunnels.

only be shut or opened from the inside; air shafts made ventilation possible, and residents could fully function, with a church (the area, as I said, was Christian, even after the Muslim conquest). Tunnels connected everything, and some were pretty narrow, though living quarters were “duplex,” and in any case at least three times the size of a room in London. Many of the tunnels were pretty narrow and not very high—which tested my claustrophobia, but the peek holes where the locals could attack the invaders reminded me of the Viet Cong area called Cu Chi tunnels.

Fourth, I wanted to climb a peak, and while the 13,000 foot volcano that caused this landscape was out of reach, the 4,300 foot Uchisar fortress, right  behind my guest house (I didn’t realize I was living in the expensive real estate—the fortress commands views, and views command room rates), was convenient. At the top, there were shallow graves for the Byzantines, but apparently the fortress had tunnels that connected with the underground cities. After 700 or 800 years of being attacked, I suppose the Byzantines got pretty good at defensive strategies.

behind my guest house (I didn’t realize I was living in the expensive real estate—the fortress commands views, and views command room rates), was convenient. At the top, there were shallow graves for the Byzantines, but apparently the fortress had tunnels that connected with the underground cities. After 700 or 800 years of being attacked, I suppose the Byzantines got pretty good at defensive strategies.

Finally—and this was the Turkish delight—at 5 am, a van picked me up to take me to a field strewn with hot air balloons.

The Lonely Planet suggestion was, “If you’re ever going to do a hot air balloon, Cappadocia is the place.” I took that to heart. There were about 70 that took off today, taking advantage of the relative calm in the morning, with the light wind. The captain was hilarious (which was helpful since I  was nervous), and took us close up and up and over. What a great view from the air, and what a smooth ride. We landed on the trailer, and celebrated with champagne. It was 7 am.

was nervous), and took us close up and up and over. What a great view from the air, and what a smooth ride. We landed on the trailer, and celebrated with champagne. It was 7 am.

That was my homage to Jules Verne. When I was younger (notice that!), a picture that really moved me was Around the World in 80 Days. That may well have been inspiration realized, not just in the hot-air balloon trip, but in the wanderlust that’s captivated me the last 20 years.

I hope you find a book, a movie, a friend, who will inspire a similar quest for adventure and self understanding. Bring on the next adventure.

this until the snows come—and it gets bitterly cold, our guide says, with lots of snow. Some of that is obvious when I look out my window at the volcano largely responsible for the eruptions that created Cappadocia—it’s over 4000 meters, or over 12,000 feet, still snowcapped, and betraying that volcano shape that hides the fact that the last eruption was 2 million years ago, and the guide assured me it was dormant.

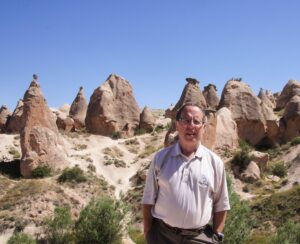

this until the snows come—and it gets bitterly cold, our guide says, with lots of snow. Some of that is obvious when I look out my window at the volcano largely responsible for the eruptions that created Cappadocia—it’s over 4000 meters, or over 12,000 feet, still snowcapped, and betraying that volcano shape that hides the fact that the last eruption was 2 million years ago, and the guide assured me it was dormant. that have eroded in various ways; the scenery consists of “fairy chimneys” and rock formations that could be in the Great Sand Dunes, hoodoo type formations with balanced rocks on top; I think the description of one valley is “like the moon,” and another is called imagination valley, where our guide was able to point out formations that looked like “Napoleon’s Hat,” etc.

that have eroded in various ways; the scenery consists of “fairy chimneys” and rock formations that could be in the Great Sand Dunes, hoodoo type formations with balanced rocks on top; I think the description of one valley is “like the moon,” and another is called imagination valley, where our guide was able to point out formations that looked like “Napoleon’s Hat,” etc.

fact, the guest house where I’m staying is a modified cave house. They created whole villages in the “fairy chimneys,” rather like the Puebloan in the Southwest—except the homes were individual, and not communal, though we did see some communal kitchens. Like the native Americans at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, the

fact, the guest house where I’m staying is a modified cave house. They created whole villages in the “fairy chimneys,” rather like the Puebloan in the Southwest—except the homes were individual, and not communal, though we did see some communal kitchens. Like the native Americans at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, the

there were still some magnificent churches, partly because of the importance of Cappadocia in church history. I had Eusebius as bishop of Caesarea, which he was—in Palestine—but there were three local Saints that were featured in the churches here.

there were still some magnificent churches, partly because of the importance of Cappadocia in church history. I had Eusebius as bishop of Caesarea, which he was—in Palestine—but there were three local Saints that were featured in the churches here.

and had to catch the plane for Cappadocia at 5 am, which made me glad I had nothing else scheduled today when I got to Ushidar, one of the “cities” in the area. The gateway to Cappadocia is Kayseri, a town the Romans called Caesarea. Yes, the empire stretched from London through Asia minor, and through much of north Africa. One of the prominent early Christians in the biography of Constantine I’m reading was Bishop Eusebius, and tomorrow I guess I’ll get to see remains of the old churches. What’s interesting is the landscape, sort of like being in the Badlands—except that people carved homes and churches and hid from authority, especially, for about 700 years.

and had to catch the plane for Cappadocia at 5 am, which made me glad I had nothing else scheduled today when I got to Ushidar, one of the “cities” in the area. The gateway to Cappadocia is Kayseri, a town the Romans called Caesarea. Yes, the empire stretched from London through Asia minor, and through much of north Africa. One of the prominent early Christians in the biography of Constantine I’m reading was Bishop Eusebius, and tomorrow I guess I’ll get to see remains of the old churches. What’s interesting is the landscape, sort of like being in the Badlands—except that people carved homes and churches and hid from authority, especially, for about 700 years.

, the tomb with the sculptures of Alexander the Great drawing the most attention; the King buried in it had battled on the side of Alexander, and the frieze commemorates their relationship.

, the tomb with the sculptures of Alexander the Great drawing the most attention; the King buried in it had battled on the side of Alexander, and the frieze commemorates their relationship.

enjoyed was “Istanbul through the Ages,” an exhibit that featured what was and what is, with some wonderful explanations of what happened. I learned, for example, that Bosphorus means “ox ford,” and it came to prominence when Darius and the Persians used a series of boats as a bridge to advance to battle the Greeks; I think one of the monuments to the Greek victory eventually wound up in Istanbul. (Is it time for Greece to get indignant?)

enjoyed was “Istanbul through the Ages,” an exhibit that featured what was and what is, with some wonderful explanations of what happened. I learned, for example, that Bosphorus means “ox ford,” and it came to prominence when Darius and the Persians used a series of boats as a bridge to advance to battle the Greeks; I think one of the monuments to the Greek victory eventually wound up in Istanbul. (Is it time for Greece to get indignant?)

area on the other side of the Golden Horn to the Dolmabahce Palace. I was not prepared for the 1850s neoclassical and rococo palace Abdulhamid built to replace the Topkapi Palace and indicate Turkey was a European power at a time when the Ottomans were desperately trying to modernize to keep the empire together. Greece had already sought its independence; I think Egypt had gotten its; Turkey, England and France were fighting Russia in the Crimea—and Abdulhamid had spent money building a palace that rivaled the big

area on the other side of the Golden Horn to the Dolmabahce Palace. I was not prepared for the 1850s neoclassical and rococo palace Abdulhamid built to replace the Topkapi Palace and indicate Turkey was a European power at a time when the Ottomans were desperately trying to modernize to keep the empire together. Greece had already sought its independence; I think Egypt had gotten its; Turkey, England and France were fighting Russia in the Crimea—and Abdulhamid had spent money building a palace that rivaled the big ones in Western Europe. My favorite room reflects the efforts of Germany to woo the Ottomans—a vase from Kaiser Wilhelm, with his picture on it, and a statue and picture of Otto von Bismarck, the German chancellor during the last half of the 19th century, as Germany and the Ottoman Empire forged the ties that helped bind them in a death dance in World War I based on their common enmity to Russia that would topple both the German and Ottoman Empires (as well as their Austro-Hungarian allies)

ones in Western Europe. My favorite room reflects the efforts of Germany to woo the Ottomans—a vase from Kaiser Wilhelm, with his picture on it, and a statue and picture of Otto von Bismarck, the German chancellor during the last half of the 19th century, as Germany and the Ottoman Empire forged the ties that helped bind them in a death dance in World War I based on their common enmity to Russia that would topple both the German and Ottoman Empires (as well as their Austro-Hungarian allies)

time. Plus, the architect of the mosque was the famous Sinan, and I wanted to be sure to see one of his monumental buildings.

time. Plus, the architect of the mosque was the famous Sinan, and I wanted to be sure to see one of his monumental buildings. conquest institution, a covered market of 4,000 shops that would do China proud—everything from copperware to clothes, utensils to jewelry—low to high prices. The streets were pretty crowded with shoppers and tourists (sometimes one and the same), but every so often would be a gem—the

conquest institution, a covered market of 4,000 shops that would do China proud—everything from copperware to clothes, utensils to jewelry—low to high prices. The streets were pretty crowded with shoppers and tourists (sometimes one and the same), but every so often would be a gem—the