The last day in China was typical: spectacular new things to do and see. An early morning wake-up took us in BanNa prefecture to Wild Elephant Valley, the home of one of the largest herd of elephants in China (the elephant and the peacock are venerated in the area, as they are in nearby Thailand, Laos and Cambodia). The park included other natural items–a butterfly zoo, a bird zoo, local minorities (have you ever eaten spicy wild sparrows?) and an elephant show in case you don’t see elephants. We were  hiking one of the trails (with a sign that said, “Be off the trails from 6 p.m. until 8 a.m. because that’s when the elephants use them) when armed guards blocked us from going further because there was a herd of elephants on the prowl. Because they have poor eyesight and can become enraged, the park wants to keep people away from them. The best way to see the herd is from a funicular, which was not running. As I told the guide, if you want to be sure of seeing elephants, go to the zoo. He’s been to the park 100 times and seen them twice from the gondola.

hiking one of the trails (with a sign that said, “Be off the trails from 6 p.m. until 8 a.m. because that’s when the elephants use them) when armed guards blocked us from going further because there was a herd of elephants on the prowl. Because they have poor eyesight and can become enraged, the park wants to keep people away from them. The best way to see the herd is from a funicular, which was not running. As I told the guide, if you want to be sure of seeing elephants, go to the zoo. He’s been to the park 100 times and seen them twice from the gondola.

In the afternoon, before the plane ride, I asked to be taken to the biggest park in Jinhong, which had the distinction of having the oldest Buddhist temple in the area. The Lord Buddha was reputed to have visited the temple.  As a bonus, the lake in the park had a zip line, which, for a fee, enabled me to get across quickly; there was a cameraman at the other end, who, for a fee, provided me with a souvenir (for about $1.20, I have a 5×7 laminated picture with a Chinese inscription telling the where and the date. I told you the tourist infrastructure was quite well developed!). They have the picture-taking services everywhere; at the bird exhibit in the Wild Elephant Valley, a trained parrot swoops to you if you hold your hand out, and you can have a picture of that, too!

As a bonus, the lake in the park had a zip line, which, for a fee, enabled me to get across quickly; there was a cameraman at the other end, who, for a fee, provided me with a souvenir (for about $1.20, I have a 5×7 laminated picture with a Chinese inscription telling the where and the date. I told you the tourist infrastructure was quite well developed!). They have the picture-taking services everywhere; at the bird exhibit in the Wild Elephant Valley, a trained parrot swoops to you if you hold your hand out, and you can have a picture of that, too!

One of the  most interesting business opportunities came from a man who in a 1995 movie played Chiang Kai-shek. For 30 renminbi you could take a picture with him. I pondered it and decided that having a picture with him in front of the sign that touted the merits of the picture might be nice for my marketing class. I bargained one picture on my camera for ten renminbi. He agreed, put on his military uniform (he did look like the generalissimo), and my guide took a picture. The man then assumed another position when I handed him the bill, and suggested another picture (one with me bribing him?), for which he then demanded another 10 RMB. I think maybe he had studied the part too well.

most interesting business opportunities came from a man who in a 1995 movie played Chiang Kai-shek. For 30 renminbi you could take a picture with him. I pondered it and decided that having a picture with him in front of the sign that touted the merits of the picture might be nice for my marketing class. I bargained one picture on my camera for ten renminbi. He agreed, put on his military uniform (he did look like the generalissimo), and my guide took a picture. The man then assumed another position when I handed him the bill, and suggested another picture (one with me bribing him?), for which he then demanded another 10 RMB. I think maybe he had studied the part too well.

When the guide put me on the plane, I realized I was beginning the Long March home (the long march was the epic journey that took Mao’s forces in the mid-1930s from eastern China all the way to near LiJiang to cross the Yangtze–there called the river of Golden Sands–and back to Yan ‘an, north of Xian in 1936).

Two things about where BanNa rates in history. It wasn’t until 1961

that one of the major leaders made it down there. There’s a Zhou En-lai statue commemorating his attendance at the water splashing festival that year; and the memorial to the heroes (martyrs) of the revolution from the prefecture was erected in 1996. Almost 50 years after the creation of the new China.

that one of the major leaders made it down there. There’s a Zhou En-lai statue commemorating his attendance at the water splashing festival that year; and the memorial to the heroes (martyrs) of the revolution from the prefecture was erected in 1996. Almost 50 years after the creation of the new China.

My 8,000-plus mile long march started Monday evening with a short jump to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province. I’ve been there 3 times, and remember vividly my first visit in 1990: we were in a hotel that told us to shower between 6 and 7, that being the only time it had hot water! Today, of course, it has Michigan Avenue and elegant brand-name stores, and a world-class theater that provided a wondrous dance program, including a very famous peacock dance that I had seen in 1990. It seemed like a fitting way to pay homage to Chinese civilization, and the three weeks I’ve been able to spend in China.

The Long March (or rather the long sit) began at 5 a.m. Tuesday morning, or 4 p.m. Monday night your time. I went from Kunming to Beijing, about 3 hours, which demonstrates the breadth of China. I was wondering what I was going to do to kill the three hours between flights; that was resolved because the new airport (Shou Du, or capital airport) is now one of the largest and most confusing. The bus from terminal one to terminal three took about half an hour. When I called Carolyn to tell her I was on my way, she said, “You may have trouble getting to Chicago; there’s thunderstorms predicted.”

There were thunderstorms, which kept us on the ground in Beijing for three hours, which made my transfer of airport terminals in Seoul a little scary. I got to the gate with 20 minutes to spare (time in a plane now up to 7 hours, with the Transpacific flight to go). The trip across the Pacific is about 1 hour shorter than the trip over, making it 11 hours, rather than 13.

I grabbed the Wall Street Journal and realized that I had been in a country that controls (or tries to control) the news, and especially potentially destabilizing dissent. The front page was a story about how the Chinese government has begun to shape some of the news from the earthquake zone. Especially as parents question why so many schools collapsed; the inside contained a story about how Chinese students have become very patriotic and pragmatic, comparing the Tiananmen generation with the current students, who basically back the government’s desire for order and stability (and economic growth).

The paper also pointed out something I saw, but didn’t read about in the news, about the shortages of diesel fuel, creeping inflation, and a job crunch affecting college students. And, of course, for the week I spent in Korea, the 20 percent popularity of the Korean president and the uprising that has delayed the negotiations with the United States for beef exports (popular pressure here is different)!

Anyway, the plane got in early enough for me to catch the 7 p.m. shuttle to Bloomington, and I was home about 26 hours after I left Kunming. The long sit was over. Chairman Mao once pointed out that Americans were not Asians, and sooner or later they would have to go home. I don’t think he was talking about me in particular, but I’m glad it was later, rather than sooner.

I hope you understand, as I’ve told our students, my passion for Asia, and the importance it will play in the future of the world.

When do I get to go back?

The map says I’m in China, but this corner of the kingdom as much resembles its southern neighbors as much as it does the far-off Beijing.

The map says I’m in China, but this corner of the kingdom as much resembles its southern neighbors as much as it does the far-off Beijing. well. When I was in Burma a few years ago, I had our driver stop to see what was available in a store–all Chinese goods. The road to Mandalay was clogged with trucks making the trek from Kunming, and hotels jammed with Chinese drivers.

well. When I was in Burma a few years ago, I had our driver stop to see what was available in a store–all Chinese goods. The road to Mandalay was clogged with trucks making the trek from Kunming, and hotels jammed with Chinese drivers. While those ties are increasingly supplemented with infrastructure (new roads and railroads) the ties are historical. The Dai minority here use a script that is Thai-like. The souvenir stores feature Thailand tee-shirts, and Burmese jewelry. Even closer (and unusual for China) is the Buddhism, which is of the colorful Southeast Asian variety, rather than the grey/brown earth tones of Japan/Korea and elsewhere in China.

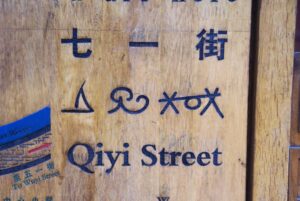

While those ties are increasingly supplemented with infrastructure (new roads and railroads) the ties are historical. The Dai minority here use a script that is Thai-like. The souvenir stores feature Thailand tee-shirts, and Burmese jewelry. Even closer (and unusual for China) is the Buddhism, which is of the colorful Southeast Asian variety, rather than the grey/brown earth tones of Japan/Korea and elsewhere in China. We went to a Dai village (increasingly rare, but preserved for historical and tourist purposes), to an old temple, where the guide said the Lord Buddha had come. The street names in town also have Chinese/English/Dai writing, in a frame that looks like it could have

We went to a Dai village (increasingly rare, but preserved for historical and tourist purposes), to an old temple, where the guide said the Lord Buddha had come. The street names in town also have Chinese/English/Dai writing, in a frame that looks like it could have  come from Thailand.

come from Thailand.

not for tourism, most of the world, I’m convinced, would look the same.

not for tourism, most of the world, I’m convinced, would look the same.

victory, they have a splashing party, which sounds like a good reason to party. Last night (having been to a village and a rainforest museum) I went to a spectacular show (the provincial government spent over $1 million U.S. on it) where I got splashed!

victory, they have a splashing party, which sounds like a good reason to party. Last night (having been to a village and a rainforest museum) I went to a spectacular show (the provincial government spent over $1 million U.S. on it) where I got splashed! If Qingdao (or as I prefer, Tsingtao) was fun to wander aimlessly because it was a German Colony, my next city, Lijiang, was fun to wander around aimlessly because it was back in China–or rather, because it wasn’t “Chinese.”

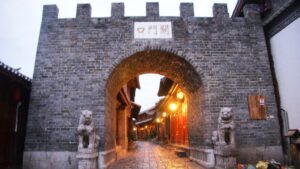

If Qingdao (or as I prefer, Tsingtao) was fun to wander aimlessly because it was a German Colony, my next city, Lijiang, was fun to wander around aimlessly because it was back in China–or rather, because it wasn’t “Chinese.”

have a pictograph language that they still use, and a unique architectural style that has made Lijiang the mecca for trekkers and tourists that it once was when it was a trading post on the “old horse road.” The Naxi nationality (that’s how the Chinese refer to their minorities) number around 300,000, and seem to peacefully coexist with the Chinese. As my guide (a Naxi but also a member of the Communist Party put it), “we embraced many of the Han things and became civilized.”

have a pictograph language that they still use, and a unique architectural style that has made Lijiang the mecca for trekkers and tourists that it once was when it was a trading post on the “old horse road.” The Naxi nationality (that’s how the Chinese refer to their minorities) number around 300,000, and seem to peacefully coexist with the Chinese. As my guide (a Naxi but also a member of the Communist Party put it), “we embraced many of the Han things and became civilized.” One of the sights I insisted on seeing was a “red hat” monastery. Not just the Naxi nationality got driven out of central China, but apparently the Tibetan “losers” got driven out as well. The “yellow hats” predominate in Lhasa–but there are a number of “red hat” monasteries in Lijiang area. Hence, many of the buildings have a Tibetan influence, a Naxi influence, and a Han influence.

One of the sights I insisted on seeing was a “red hat” monastery. Not just the Naxi nationality got driven out of central China, but apparently the Tibetan “losers” got driven out as well. The “yellow hats” predominate in Lhasa–but there are a number of “red hat” monasteries in Lijiang area. Hence, many of the buildings have a Tibetan influence, a Naxi influence, and a Han influence. I stayed in a new building (old style) in the old city, which has a confusing maze of cobblestone streets (no cars, which is a blessing in China!), and got up early (the sun is at least an hour later here than in Beijing, but China is ALL one time zone), and wandered around taking pictures with no tourists in them. The hotel (and this may indicate the time warp) had a magazine touting its well-known visitors, including “Comrade Hu Jin-tao,” the first time in years I’ve heard anyone refer to anyone in China as comrade!

I stayed in a new building (old style) in the old city, which has a confusing maze of cobblestone streets (no cars, which is a blessing in China!), and got up early (the sun is at least an hour later here than in Beijing, but China is ALL one time zone), and wandered around taking pictures with no tourists in them. The hotel (and this may indicate the time warp) had a magazine touting its well-known visitors, including “Comrade Hu Jin-tao,” the first time in years I’ve heard anyone refer to anyone in China as comrade! The centerpiece of the city is the home of the “local king,” the Mu family, which looks for all the world like a small version of the Forbidden C ity. Which means, I think, that it’s always glorious to be rich.

The centerpiece of the city is the home of the “local king,” the Mu family, which looks for all the world like a small version of the Forbidden C ity. Which means, I think, that it’s always glorious to be rich.

religion, the Dongba, which is based on wisdom and age (I could be a Dongba). There are 9 Dongba shamans, who are the most wonderfully photogenic people I’ve met in China.

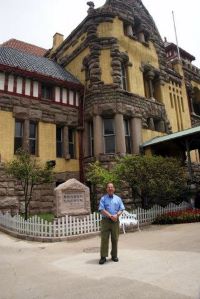

religion, the Dongba, which is based on wisdom and age (I could be a Dongba). There are 9 Dongba shamans, who are the most wonderfully photogenic people I’ve met in China. While Japan surrendered Qingdao to the Chinese in 1922, the city still has a German feel to it; the architecture remains as silent testimony to the German patrimony here, especially in the reasonably compact old city (which is why I like wandering around). Since I was here last (probably about ten years ago), in fact, new museums have opened to highlight the German background (and the Japanese conquest in 1914 and again as part of World War II).

While Japan surrendered Qingdao to the Chinese in 1922, the city still has a German feel to it; the architecture remains as silent testimony to the German patrimony here, especially in the reasonably compact old city (which is why I like wandering around). Since I was here last (probably about ten years ago), in fact, new museums have opened to highlight the German background (and the Japanese conquest in 1914 and again as part of World War II).