We were in Chengde, 130 miles or so north of Beijing. It’s about 15 degrees cooler, 1500 feet higher, and has about 23 million fewer inhabitants. We’ve gone back to China about 10 years ago, maybe more, but it does boast a McDonalds and a KFC franchise. It is pleasant to visit a smaller city, if only for the slower pace and the smaller crowds!

Having spent yesterday in the Yongle mode of the 15th century, we’ve gone ahead in some ways into Qing period, from 1644 till 1911. The last stop we had in Beijing belonged to that period—the famous Summer Palace built by the infamous Empress Dowager, Cixi, who was the mastermind behind

China from 1861 until her death in 1908. She kept her position mostly through guile, with a dash of poison—several emperors for whom she served as regent died mysteriously.

The 1881 Summer Palace, one of the must sees in Beijing is her  legacy. She constructed it northwest of Beijing (which has grown to absorb it) to replace the Yuan Ming Yuan, a summer palace reputedly one of the wonders of the world, which the allied armies, who torched Beijing in 1860, left in ruins. Those ruins today rest nearby, and if I have time on our return to Beijing, I hope to get out there. They are hauntingly part of the “road to rejuvenation,” the exhibit I saw this morning at the National Museum of China, a stupendous building that is so big it seems relatively empty of artefacts, although I suspect there were thousands. A separate exhibit that is difficult to find deals with the road to rejuvenation, the route the Communist Party traveled in undoing

legacy. She constructed it northwest of Beijing (which has grown to absorb it) to replace the Yuan Ming Yuan, a summer palace reputedly one of the wonders of the world, which the allied armies, who torched Beijing in 1860, left in ruins. Those ruins today rest nearby, and if I have time on our return to Beijing, I hope to get out there. They are hauntingly part of the “road to rejuvenation,” the exhibit I saw this morning at the National Museum of China, a stupendous building that is so big it seems relatively empty of artefacts, although I suspect there were thousands. A separate exhibit that is difficult to find deals with the road to rejuvenation, the route the Communist Party traveled in undoing  the century of humiliation. Some of the pictures in that exhibit (the captions were mostly in Chinese, but it’s the Chinese vocabulary I learned in the early 1970s of revolution and imperialism; my favorite was a pamphlet by renown missionary Young J. Allen extolling British imperialism in India) showed foreign troops ransacking that palace and sitting on the imperial throne. And they got a medal for it!

the century of humiliation. Some of the pictures in that exhibit (the captions were mostly in Chinese, but it’s the Chinese vocabulary I learned in the early 1970s of revolution and imperialism; my favorite was a pamphlet by renown missionary Young J. Allen extolling British imperialism in India) showed foreign troops ransacking that palace and sitting on the imperial throne. And they got a medal for it!

The new summer palace demonstrated that the Qings could spend money on themselves, building halls, lakes, islands, Buddhist temples, and what the Guinness Book of Records says is the largest painted corridor in the world, with hand-painted illustrations from Chinese literature on the arches that support this covered walkway. The courtyard in front of the Empress Dowager’s bedroom contains the phoenix (symbol of the Empress) in the place of honor, exchanging places with the dragon (symbol of the Emperor), more accurately reflecting power in Ci xi’s empire than the titles. It also contains the largest single rock in China used for display.

The route to Chengde, a superhighway with relatively little traffic, and a view and access to still another reconstructed section of the Great Wall, one where you can do a five-mile hike, demonstrates epigrammatically the difference between the infrastructure in China and India; we arrived quickly, and not having felt we’d spent the ride in a washing machine.

Chengde’s reputation and attraction as a tourist site (the province is striving to make it an international tourist city) rests on the legacy of two Qing emperors—Kangxi and Qianlong. Imagine if US history had been dominated for 120 years by two presidents, and you get an idea of what those two men meant to China from the late 1600s until almost the 18th century. Kangxi ruled for 61 years as emperor, and according to a show (more about that) we saw tonight, helped transform the Manchus from north of the Great Wall barbarians into—what else—civilized Chinese, scholars respectful of Chinese language, history, traditions, and the religions (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism). Both had an understandable orientation to the north, being related to the Tibetans and Mongolians, and being wary of the other barbarians north of the wall.

Chengde’s reputation and attraction as a tourist site (the province is striving to make it an international tourist city) rests on the legacy of two Qing emperors—Kangxi and Qianlong. Imagine if US history had been dominated for 120 years by two presidents, and you get an idea of what those two men meant to China from the late 1600s until almost the 18th century. Kangxi ruled for 61 years as emperor, and according to a show (more about that) we saw tonight, helped transform the Manchus from north of the Great Wall barbarians into—what else—civilized Chinese, scholars respectful of Chinese language, history, traditions, and the religions (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism). Both had an understandable orientation to the north, being related to the Tibetans and Mongolians, and being wary of the other barbarians north of the wall.

Partly to keep those barbarians in check, and partly because the temperature in Chengde is more temperate, and partly because the north afforded the grasslands that warriors on horseback needed to hone their skills, Kangxi established a mountain summer villa here, a predecessor to the summer palace we saw in Beijing, and five times as large as the

Forbidden City. It contains three artificial lakes, bedrooms and meeting rooms (the ruling family moved here for six months a year) and conducted the affairs of state here; probably the most famous encounter was with the English emissary, Lord McCartney, who sought to open relations with China in 1793. Qianlong essentially told the Englishman that China had everything it needed, thank you; and McCartney refused to bow to the Emperor and perform the rituals that the Asian states had done with China. China’s relations with the rest of Asia had been as a superior to vassals, and the attitude of superiority still colors China’s view of the world. It is a striking place that reflects the power and wealth of the Manchus. As I pointed out to my class, the combination of overwhelming ego and overwhelming wealth and overwhelming power were overwhelming. (One of my students noted that if that was what was required to be an emperor, I had at least one of those attributes).

Forbidden City. It contains three artificial lakes, bedrooms and meeting rooms (the ruling family moved here for six months a year) and conducted the affairs of state here; probably the most famous encounter was with the English emissary, Lord McCartney, who sought to open relations with China in 1793. Qianlong essentially told the Englishman that China had everything it needed, thank you; and McCartney refused to bow to the Emperor and perform the rituals that the Asian states had done with China. China’s relations with the rest of Asia had been as a superior to vassals, and the attitude of superiority still colors China’s view of the world. It is a striking place that reflects the power and wealth of the Manchus. As I pointed out to my class, the combination of overwhelming ego and overwhelming wealth and overwhelming power were overwhelming. (One of my students noted that if that was what was required to be an emperor, I had at least one of those attributes).

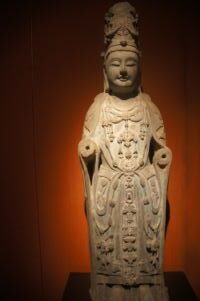

The area is dotted with temples built by the royal family, and we visited two

of them, both built by the reverent Buddhist, Qianlong. One was to make his northern guests feel at home, and looks rather like the Potala Palace in Lhasa, which would make the Dalai Lama, the head of Tibetan Buddhism feel comfortable, but as our guide pointed out, there were subtle hints that while the Dalai Lama was a friend, the Emperor was still the boss. Some of

of them, both built by the reverent Buddhist, Qianlong. One was to make his northern guests feel at home, and looks rather like the Potala Palace in Lhasa, which would make the Dalai Lama, the head of Tibetan Buddhism feel comfortable, but as our guide pointed out, there were subtle hints that while the Dalai Lama was a friend, the Emperor was still the boss. Some of  the hints were not so subtle, such as the Chinese style roofs atop the Tibetan style buildings, but then, in Lhasa, there’s a plaque to one of the first treaties signed with Tibet, in which the Chinese stated they were the “big brother;” that’s been the attitude toward Tibet ever since.

the hints were not so subtle, such as the Chinese style roofs atop the Tibetan style buildings, but then, in Lhasa, there’s a plaque to one of the first treaties signed with Tibet, in which the Chinese stated they were the “big brother;” that’s been the attitude toward Tibet ever since.

This evening we visited the new new China’s view of the Kangxi period—a show developed by the film studio that developed the Olympic opening show. It was another over-the-top tourist attraction (exceeding, by far, the sedan chairs that tourists can now ride!), with 300 horses and 600 actors,  and animation you would not believe. Having been here, though, I can believe it. One of the messages in it was that Kangxi recovered Taiwan, which held out against the Qing until the 1680. On the other hand, Qing fortune in the 1680s also brushed up against the aggressive Russian state, then moving into Asia. The Treaty of Nerchinsk, between the Qing and the Romanovs was one of the first modern treaties, an opening step that would eventually help make the Ming and Qing part of what the Chinese like to call their “feudal past.”

and animation you would not believe. Having been here, though, I can believe it. One of the messages in it was that Kangxi recovered Taiwan, which held out against the Qing until the 1680. On the other hand, Qing fortune in the 1680s also brushed up against the aggressive Russian state, then moving into Asia. The Treaty of Nerchinsk, between the Qing and the Romanovs was one of the first modern treaties, an opening step that would eventually help make the Ming and Qing part of what the Chinese like to call their “feudal past.”

Yongle was not responsible for the Great Wall, but the Great Wall we have come to know was a product of the Ming dynasty, which, as I said, lived in fear of invasion from the north. The Ming resurrected a defense system that predated even Qin Shi-huang, the first emperor, who consolidated the wall his predecessors had built. The Ming wall ran over 4,000 miles, from Shanhaiguan, where it met the sea to Jiayuguan, where it extends into the desert. The stretch we climbed was within 30 miles of Beijing (if you think about the possibility of invasion from the north, bear in mind that’s the distance from Seoul to the 38th parallel in Korea), the product, I think of the post-Mao dynasty, which has been building tourist attractions like crazy.

Yongle was not responsible for the Great Wall, but the Great Wall we have come to know was a product of the Ming dynasty, which, as I said, lived in fear of invasion from the north. The Ming resurrected a defense system that predated even Qin Shi-huang, the first emperor, who consolidated the wall his predecessors had built. The Ming wall ran over 4,000 miles, from Shanhaiguan, where it met the sea to Jiayuguan, where it extends into the desert. The stretch we climbed was within 30 miles of Beijing (if you think about the possibility of invasion from the north, bear in mind that’s the distance from Seoul to the 38th parallel in Korea), the product, I think of the post-Mao dynasty, which has been building tourist attractions like crazy.

chronicled in The Last Emperor, winding up as a gardener in Beijing (after being puppet emperor of Manchukuo under the Japanese from 1932 until 1945) It has been a public museum since.

chronicled in The Last Emperor, winding up as a gardener in Beijing (after being puppet emperor of Manchukuo under the Japanese from 1932 until 1945) It has been a public museum since.