From what’s been called Europe’s last “artificial” country—Brussels

From what’s been called Europe’s last “artificial” country—Brussels

I don’t know why I’d not considered going to Brussels before this trip; it’s only an hour and twenty minutes by train from Paris. It’s also considered the “center of Europe” (so the guide told us) because it’s close to the Netherlands, Berlin, etc. That’s of course been one of its hazards historically, having been on the invasion route between France (which pummeled the city under Louis XIV) and Germany, which came through Belgium in 1914 and 1939.

Studying the European Union as we were, we had to come here, and in the next two days we will be visiting with officials of the EU. Today, when we got here from Paris, we got an introduction to the rather lengthy history of the area, which has been “Belgium” since 1830. It’s a kingdom of 10 million people, 20% of whom work for one government or another. There are three federations within Belgium—the French speakers in the south, the Dutch speakers in the north, and the city of Brussels, where signs are in both French and Dutch. In medieval times, the city was the center of trade—there were over 30 guilds, and for a time, the Low Countries were battled over by Spain and France especially. Charles V (king of Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, etc.) was born here, and Charles Quinz is the name of one of the 1000 beers that are locally brewed, many of ancient duration, and many in monasteries. The most famous come from the Trappists.

Skipping ahead to the Napoleonic wars, Brussels was awarded at the Congress of Vienna to the Dutch, but in 1830, rebelled successfully, became “Belgium,” and “hired” King Leopold, whose family still rules as King of the Belgians. The royal family’s palace is enormous, but not really visible from the road; it was the wealth of Leopold II, gained from his personal possession of the Congo, which he ruled personally and ruthlessly, bringing much of the wealth to beautify the city. He was so ruthless that the Parliament took the colony away from him, though the Belgian Congo continued to exist until 1960 I believe.

The guilds give the city its outstanding central area, a town square with two of my favorite architectural styles: a palace and a town hall that are Gothic (the town hall has a steeple that could be mistaken for a church) and the other buildings, mostly built to house the guilds (the baker, the brewer, etc.), are from the baroque period, stylishly

The guilds give the city its outstanding central area, a town square with two of my favorite architectural styles: a palace and a town hall that are Gothic (the town hall has a steeple that could be mistaken for a church) and the other buildings, mostly built to house the guilds (the baker, the brewer, etc.), are from the baroque period, stylishly including the gold trimming characteristic of baroque, and resplendent tonight in the setting sun.

including the gold trimming characteristic of baroque, and resplendent tonight in the setting sun.

Until the 1960s, Belgium was one of the more industrial countries in Europe, possessed as it is of coal. As such, it was part of the initial organizations—the Coal and Steel Community—that presaged the European Union. Ironically, one of the directives of that community was to phase out the coal industry in Belgium, forcing the country to diversify.

The result has been a country that has turned to government (as I mentioned above, 20% or so of its citizens will be working for one of the government offices here), and to some specialty products like chocolate (for a chocoholic, this place could be deadly), and at least here, tourism.

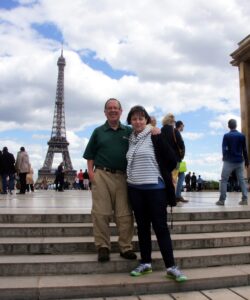

I think you can see why I wanted to start with being here, because yesterday I was happy as could be in Paris. That was a million years ago—or at least yesterday.

The day started badly for me because I was convinced I wanted to participate in the bicycle tour de France, or at least as much as I could get early in the morning. There was a bike stand nearby, but for some reason, it would not take the credit cards I had as down payment—the rentals were cheap (about 2$ a day, plus time), but required a $ 150 bike deposit against a credit card. Annoyed, I went for a walk that resulted in the discovery of a restaurant (more later about that).

Most of the day we spent with an alum, Miranda Crispin, who graduated IWU in 2000 with a degree in musical theater, and for several years afterwards she taught musical theater at colleges in Michigan, Indiana, and Wisconsin. She realized that what she needed if she wanted to continue her career in teaching was more experience in theater, which led her back to Paris. I say back here because she came to IWU because she wanted to study abroad, and our university was one of the few which allowed her to travel to France and still graduate on time.

Most of the day we spent with an alum, Miranda Crispin, who graduated IWU in 2000 with a degree in musical theater, and for several years afterwards she taught musical theater at colleges in Michigan, Indiana, and Wisconsin. She realized that what she needed if she wanted to continue her career in teaching was more experience in theater, which led her back to Paris. I say back here because she came to IWU because she wanted to study abroad, and our university was one of the few which allowed her to travel to France and still graduate on time.

She came back and started a travel company that has been successful, but

With Miranda Crispin (2000)she has also started a musical theater group to bring off- Broadway plays to the City of Lights. She gave us an unusual look at the life of an expatriate in France, and a different view of the EU (the International Herald Tribune yesterday noted that French opinion had swung from 60% in favor of the EU a year ago to 40% this year, partly because of the 11% unemployment in France).

She also introduced us to a friend of hers, a young woman from Sydney, Australia, who is working for Radio France doing their English language broadcasts. She regaled us with stories on how journalism is more opinionated in France than in the English-speaking countries. One example was of the flight of millionaires from France because of a recently enacted tax increase. I remember reading about a film actor who renounced his French citizenship in favor of Russian. She said the headline in the news was roughly, “Good riddance.” As I said, it was a very different view of life in the European Union!

Professor Pana and I went out to the restaurant I had discovered on my morning walk–in the Place de Vosges, a square that dates to the 1620s, with a covered arcade around it, and a statue of Louis XIII within it. We went to the Palais Royal restaurant, which was next to the house of Victor Hugo (when he wasn’t living in Brussels), where we had a quintessentially French meal—coq au vin and leg of lamb.

We met the students later for the evening tour of the Seine, and then celebrated a birthday on the trip in French style. I got to see “Midnight in Paris” and it wasn’t produced by Woody Allen.

We met the students later for the evening tour of the Seine, and then celebrated a birthday on the trip in French style. I got to see “Midnight in Paris” and it wasn’t produced by Woody Allen.

One of the culinary treats in Brussels is moule (mussels), and as I told one of our students before we went out for dinner, “You can really get muscles here.”

Most of the traffic in the Louvre, not surprisingly, was in the European section, where it has a strong holding in pictures of and about the French Revolution (not the collection of the Bourbons!)—Ingres and David and Delacroix, for example, with the famous painting of Napoleon’s coronation ala Charlamagne, where I think he took the crown from the Pope and put it on his own head.

Most of the traffic in the Louvre, not surprisingly, was in the European section, where it has a strong holding in pictures of and about the French Revolution (not the collection of the Bourbons!)—Ingres and David and Delacroix, for example, with the famous painting of Napoleon’s coronation ala Charlamagne, where I think he took the crown from the Pope and put it on his own head.

We spent the afternoon at the Chateau of Versailles, begun as a modest hunting lodge for Louis XIII, but expanded by his son, the Sun King Louis XIV, to become the premier castle, and I believe the largest, certainly in Europe, and one that puts Windsor Castle into the minor leagues. The world class attraction seemed to have attracted the world this Sunday, as the rooms were as crowded as could be. 46,000 workers labored to bring the finest the French monarchy could obtain to the Chateau. It came close to bankrupting France, a process that culminated, when the spending to fight Britain and incidentally help the US gain independence, precipitated the French Revolution. In the meantime, the Bourbon kings (XIV, XV, XVI—sounds like super bowls, don’t they) enjoyed the facilities. They say Louis XIV built it, XV enjoyed it, and XVI paid for it. We had a lively discussion involving those who have traveled elsewhere in Europe, and the closest rivals we could come up with were St. Petersburg—and the Vatican St. Peters.

We spent the afternoon at the Chateau of Versailles, begun as a modest hunting lodge for Louis XIII, but expanded by his son, the Sun King Louis XIV, to become the premier castle, and I believe the largest, certainly in Europe, and one that puts Windsor Castle into the minor leagues. The world class attraction seemed to have attracted the world this Sunday, as the rooms were as crowded as could be. 46,000 workers labored to bring the finest the French monarchy could obtain to the Chateau. It came close to bankrupting France, a process that culminated, when the spending to fight Britain and incidentally help the US gain independence, precipitated the French Revolution. In the meantime, the Bourbon kings (XIV, XV, XVI—sounds like super bowls, don’t they) enjoyed the facilities. They say Louis XIV built it, XV enjoyed it, and XVI paid for it. We had a lively discussion involving those who have traveled elsewhere in Europe, and the closest rivals we could come up with were St. Petersburg—and the Vatican St. Peters.

Budapest and Lvov come to mind–sought to mimic the leafy boulevards, the wide streets, the victory monuments, and the 6 story buildings with the mansard roofs (go to the Art Institute and see the Impressionist section and you’ll see why Paris caught the fancy of urban planners and urbanites in the 19th century).

Budapest and Lvov come to mind–sought to mimic the leafy boulevards, the wide streets, the victory monuments, and the 6 story buildings with the mansard roofs (go to the Art Institute and see the Impressionist section and you’ll see why Paris caught the fancy of urban planners and urbanites in the 19th century).

invited two of his coworkers (boss?), who described the nature of private banking to us. As they explained, they provide customer services to a limited clientele—the really wealthy in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (from this area), with a heavy emphasis on benefitting “cash rich” customers.

invited two of his coworkers (boss?), who described the nature of private banking to us. As they explained, they provide customer services to a limited clientele—the really wealthy in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (from this area), with a heavy emphasis on benefitting “cash rich” customers. crisis of the past few years, there are about 250,000 finance people in England, down from 350,000 at the onset of the crisis. In describing how to get through the barrier, they emphasized the study of foreign languages—everyone in Europe seems to know several, and some of the Universities in England pay for their students to study abroad for a year—and to “network like crazy; make every connection count.”

crisis of the past few years, there are about 250,000 finance people in England, down from 350,000 at the onset of the crisis. In describing how to get through the barrier, they emphasized the study of foreign languages—everyone in Europe seems to know several, and some of the Universities in England pay for their students to study abroad for a year—and to “network like crazy; make every connection count.”