The end of the Rhode(s)

36 hours ago we were arriving in Rhodes, the last stop on the incredible journey of the past three weeks. The now-Greek island is a destination for tourists headed for the beaches there from northern climates—they tell me that Russian tourists have become the dominant customers. Our plane, coming from Munich to Thessaloniki, had a number who were already in the beach mode, with swimming towels draped around them, ready to go in that wonderful Aegean as soon as they hopped off the plane.

36 hours ago we were arriving in Rhodes, the last stop on the incredible journey of the past three weeks. The now-Greek island is a destination for tourists headed for the beaches there from northern climates—they tell me that Russian tourists have become the dominant customers. Our plane, coming from Munich to Thessaloniki, had a number who were already in the beach mode, with swimming towels draped around them, ready to go in that wonderful Aegean as soon as they hopped off the plane.

As our cab sped toward the old town of Rhodes, I thought we might have detoured to Miami Beach, as we passed hotels and beaches….until we turned the corner and in front of us was the old town, a city that summarized so much of what we’d seen the last three weeks (and my previous four on the May trip)—the battle between East and West.

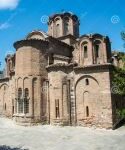

As one of the crossroads of the Eastern Mediterranean, the island has had a long history—Mycenaean, Greek (Hellenistic), Roman, Egyptian influences, Byzantine, Genoan, Turkish, Italian, etc., but the impressive fortifications that surrounded the old town were medieval, built by the Knights of St. John, which purchased the island from the Genoese (who had in turn gotten it from the Byzantines, who by that time were pawning, literally, the crown jewels to retain what was left of the Empire), in 1309. The Knights, kind of an international fraternity, had emerged during the Crusades doing hospitality and health care to the Christians in the Holy Land, and gradually

combined that with a military unit. When Saladin drove the Crusaders out of Acre and hence off the mainland, the Knights bought Rhodes and built a wall around the city.

combined that with a military unit. When Saladin drove the Crusaders out of Acre and hence off the mainland, the Knights bought Rhodes and built a wall around the city.

The hospital, now used as a museum, is an original building. Sometime after the Italians took the island from Turkey as a spoil of the Balkan Wars (1912), Mussolini had the palace of the Grand Master rebuilt to original specifications, adding such touches as mosaics from the island of Cos, and a plaque, still there, dedicating the rebuilt palace to Victor Emmanuel, then King of Italy. The overall aura is stunning, but our guide, an archeologist by training, noted that “real” archeologists were unhappy, because the palace was on the supposed site of either the Colossus of Rhodes (one of the 7 wonders of the ancient world, a statue to “freedom”) or another ancient wonder, the Temple of the Sun (Helios), and the Italians never excavated.

The hospital, now used as a museum, is an original building. Sometime after the Italians took the island from Turkey as a spoil of the Balkan Wars (1912), Mussolini had the palace of the Grand Master rebuilt to original specifications, adding such touches as mosaics from the island of Cos, and a plaque, still there, dedicating the rebuilt palace to Victor Emmanuel, then King of Italy. The overall aura is stunning, but our guide, an archeologist by training, noted that “real” archeologists were unhappy, because the palace was on the supposed site of either the Colossus of Rhodes (one of the 7 wonders of the ancient world, a statue to “freedom”) or another ancient wonder, the Temple of the Sun (Helios), and the Italians never excavated.

The city was a bastion in the swirl of Turkish-European relations, and the Turks tried two sieges—1480, and again in 1522. The latter siege, led by Suleiman the Magnificent (who got turned back at Vienna, in one of the important battles that saved Western Europe from Islam), brought 200,000 Ottoman troops against probably 10,000 knights at most. What turned the battle was a traitor in the Knights, who apparently hid the gunpowder, and shot arrows telling the Turks the knights were out of ammunition. The traitor, who had wanted to become the Grand Master (a lifetime position), was discovered, and drawn and quartered, but the Knights nonetheless surrendered. They got to leave with their weapons.

Many years later, apparently a spark went off where the gunpowder had been hidden, blowing up a number of buildings—which led to the need to rebuild the palace when the Italians took over. Most of the old buildings are still there—especially Byzantine, medieval, and Turkish, including hamams, Catholic Churches, and a Suleyman mosque much simpler than the Suleyman mosques in Istanbul.

The other highlight for us dealt with nature—not the sea, as you might have expected, but a valley where butterflies congregate in the summer, attracted by a tree that grows in abundance. The valley is a national park, so it was pretty well protected, and provided a very different ending to our trip—it had nothing to do with Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Turks, Italians, or Knights—just with nights. And we discovered Samos moscato at a dinner! Great sweet wine.

The other highlight for us dealt with nature—not the sea, as you might have expected, but a valley where butterflies congregate in the summer, attracted by a tree that grows in abundance. The valley is a national park, so it was pretty well protected, and provided a very different ending to our trip—it had nothing to do with Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Turks, Italians, or Knights—just with nights. And we discovered Samos moscato at a dinner! Great sweet wine.

We’re home now three weeks after we started—Zagreb, Varazdin, Piltovic Lakes, Split, Hvar, Korcula, Dubrovnik, Kotor, Cetinje, Sarande—Butrint, Corfu, Itea, Athens, Thessaloniki, Rhodes. I think I need a vacation from vacations—unless that means “work”!