We’ve arrived in the capital of Namibia, Windhoek, a 250 mile, 6 hour ride almost directly east from Swakopmund. Before leaving, I took the opportunity this morning to explore the seacoast city.

Walking around, I found the information center and got a list of “historic buildings” still standing. One intrigued me—the Hohenzollern House, circa 1905, in the same art deco style of so many of the buildings in Qingdao China, which the Germans treated as a colony, although it was leased for “only” 99 years. The 1907 hotel I saw looked liked the “Strand” in Qingdao also. It’s an attractive style that  has been reflected in many of the buildings since the German colonization. Not coincidentally, there’s still a Bismarck Street (I should probably say strasse), a Kaiser hotel, and a wonderful antique store named Pete’s that had everything from old helmets and books in German to various African artifacts.

has been reflected in many of the buildings since the German colonization. Not coincidentally, there’s still a Bismarck Street (I should probably say strasse), a Kaiser hotel, and a wonderful antique store named Pete’s that had everything from old helmets and books in German to various African artifacts.

My main goal was to visit the Swakopmund museum, which I was told was among the best museums in sub-Saharan Africa, and I needed at least an hour there. It’s a private museum, started in 1951 by a dentist, and augmented ever since. It is pretty comprehensive—and here were some of the highlights for me:

From the German period: a wonderful collection of stamps, covers, and an explanation of the postal service—which included a San (“Bushman”) postal carrier with a sack as a poster to use the mail, and various donkey and other means to get the mail from point A to point B. Since I collect the Qingdao German stamps, I’ve seen some of this material in auctions, but  it’s got to be an award-winning collection. I also enjoyed some of the military uniforms, including the camel corps that patrolled some of the desert areas.

it’s got to be an award-winning collection. I also enjoyed some of the military uniforms, including the camel corps that patrolled some of the desert areas.

From life in Southwest Africa, there were several restored rooms, including a reconstructed dining room complete with portrait of Wilhelm II and his wife. The dentist’s shop was reconstructed, including extracted teeth, which I had to admit, I’d never seen before in a museum. There were artifacts from the Cape/SWA boundary, and a little information on the First World War here—a British warship shelled Swakopmund and hit a pig pen…

There were interesting exhibits on the tribes—the Himba (whom I mentioned yesterday using mud as sunscreen and mosquito repellant), the Herero (rather sketchy on the uprising)—with explanations in 3 languages—Afrikaan (the Boer descendants, many of whom settled in SWA when it was mandated to South Africa), English, and German.

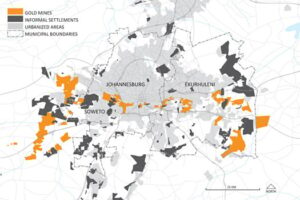

There was also a geological exhibit, including a lot of information on uranium, which came from the National Uranium institute that was the site of our business visit today. The report they gave us explained why the lobby group had broken away from the general mining group—uranium is above ground mining, and in that sense is less risky than sending miners underground. Namibia is one of the top four producers of uranium (Kazakhstan is the leading uranium producer), and the institute claims nuclear power mining has changed and nuclear energy is safer and more efficient than is generally given credit for–you be the judge. I do know that along the road was a major pipeline delivering precious water to the mines. And we have potentially another mine visit.

The bus ride fit in nicely with a flora/fauna explanation at the museum. For about half the distance we were in the Namib Desert, which is sandy and pretty sparsely vegetated. Then it became savannah, with old pretty gnarled trees, which use a minimum amount of water, and some animal life, including the warthog. By the time we got here, we’d imperceptibly gone up about 4,500 feet. That made our Brigham Young faculty happy because Provo is about that high. They may be at home, but for a flatlander who lives where overpasses are sometimes mistaken for hills, this seems pretty high. Still, it’s good to be off the bus.

The bus ride fit in nicely with a flora/fauna explanation at the museum. For about half the distance we were in the Namib Desert, which is sandy and pretty sparsely vegetated. Then it became savannah, with old pretty gnarled trees, which use a minimum amount of water, and some animal life, including the warthog. By the time we got here, we’d imperceptibly gone up about 4,500 feet. That made our Brigham Young faculty happy because Provo is about that high. They may be at home, but for a flatlander who lives where overpasses are sometimes mistaken for hills, this seems pretty high. Still, it’s good to be off the bus.