One of the questions we’ve been dealing with is whether Singapore Inc. is a government running a business, or a business running a government. The two notions are certainly connected. The government is a partial owner of some of the most successful businesses, including Singapore Airlines (if you ever get a chance to fly Singapore Air, you’ll certainly rue the day when you can’t).

It certainly directs the social polity in some ways like a business. The government has decided to limit the number of automobiles, as I think I mentioned yesterday; it auctions the right to purchase automobiles to ensure a growth of no more than a little over 1% a year (Beijing by contrast adds 1,000 cars a day to its already strained infrastructure). The price for the right this month was just under $70,000 Singapore, or about $55,000–and that’s for the right to purchase a car (with tariffs, etc., that can at least double the price of an automobile; plus gas is at least $7 a gallon). Urban planning is long-term and coherent. We learned the government has numbered each tree in an effort to maintain, if not add, greenspace.

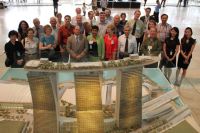

Perhaps the most pronounced government-business interchange can be attested to by the companies we visited today, spanning two really different models–agriculture (Cargill) and Medtronic (high tech pharmaceuticals).

Cargill is an interesting business, with over $110 billion in sales. Privately held, its corporate headquarters is in Minneapolis, but its operations are  around the world. While 50% of its revenues are still in the United States, the company sees Asia Pacific as its major growth area, doubling sales every 5-7 years, and has made its hub in Singapore. As the finance officer explained to us, Singapore is central to Asia, no more than 7-8 air hours from anywhere, where a headquarters in Hong Kong or China might be problematic in dealing with other regions of Asia. The Asian countries, he explained, were not self sufficient in food, and therefore needed the products and expertise that Cargill brings. For example, the company is building a $290 million factory to process chicken in Shanghai; I hope to be able to visit the plant in 2012 because the manager is a former student of mine at IWU, Omar Sadek. I met Omar about 14 years ago in Shanghai, where, a few years out of his MBA program at Baylor, he’d been given $29 million to start a chicken feed processing plant in Shanghai.

around the world. While 50% of its revenues are still in the United States, the company sees Asia Pacific as its major growth area, doubling sales every 5-7 years, and has made its hub in Singapore. As the finance officer explained to us, Singapore is central to Asia, no more than 7-8 air hours from anywhere, where a headquarters in Hong Kong or China might be problematic in dealing with other regions of Asia. The Asian countries, he explained, were not self sufficient in food, and therefore needed the products and expertise that Cargill brings. For example, the company is building a $290 million factory to process chicken in Shanghai; I hope to be able to visit the plant in 2012 because the manager is a former student of mine at IWU, Omar Sadek. I met Omar about 14 years ago in Shanghai, where, a few years out of his MBA program at Baylor, he’d been given $29 million to start a chicken feed processing plant in Shanghai.

I am fascinated with agricultural businesses, partly because, as a city boy, I don’t understand them; and partly because they are really global in nature. The US has a surplus, and without export markets, American farmers would be in trouble, and the world might go hungry. He also noted that sometimes farm policies, and especially protection of inefficient farming, are counterproductive. One of the faculty, from Mississippi, pointed out that catfish and shrimp in that state must have the origin of the product on the label, to sway consumers to buy “American” rather than Thailand’s products.

I know from my visit to Cargill in Vietnam two years ago that the company takes seriously its status as a good global citizen; there, we visited one of the 40 schools Cargill has built in areas where the government was too poor to build schools on its own.

The visit to Medtronic was even more pointed to the benefits of being in Singapore. Medtronic, one of the best companies to work for in America on the Fortune Magazine list, is another Minneapolis-based firm that moved its non-U.S. headquarters to Singapore about two years ago. The company fits the profile that Singapore Inc. desires–it’s in pharmaceuticals (makes pacemakers and stents among other goods); Singapore has given up competing with China/India/Vietnam for low-cost manufacturing. The plant manager took us through the history of the plant, which turned out its first pacemaker this month. It was instructive that his assistants numbered engineers who had come from the semi-conductor industry; that was yesterday’s industry, he said, and the Singapore government has actively recruited the “right kind” of businesses to Singapore in the same way it recruits the right universities–even recruiting competitors. There are three Singapore Inc. salespeople in the United States. He noted that while all countries gave incentives, one factor which distinguished Singapore was implementation; he had one contact in the government as an “account manager” who could resolve any problems.

The visit to Medtronic was even more pointed to the benefits of being in Singapore. Medtronic, one of the best companies to work for in America on the Fortune Magazine list, is another Minneapolis-based firm that moved its non-U.S. headquarters to Singapore about two years ago. The company fits the profile that Singapore Inc. desires–it’s in pharmaceuticals (makes pacemakers and stents among other goods); Singapore has given up competing with China/India/Vietnam for low-cost manufacturing. The plant manager took us through the history of the plant, which turned out its first pacemaker this month. It was instructive that his assistants numbered engineers who had come from the semi-conductor industry; that was yesterday’s industry, he said, and the Singapore government has actively recruited the “right kind” of businesses to Singapore in the same way it recruits the right universities–even recruiting competitors. There are three Singapore Inc. salespeople in the United States. He noted that while all countries gave incentives, one factor which distinguished Singapore was implementation; he had one contact in the government as an “account manager” who could resolve any problems.

I think what I’ve learned in our business visits is that if more businesses were run like Singapore Inc., they’d be better businesses–and that if more governments were run like Singapore’s, they’d be better governments.

Goodnight on that thought!