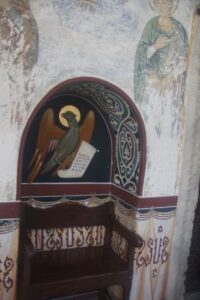

Breaking our voyage from Dubrovnik to Haifa was a stop at the island of Patmos. With the city of Chora (and a population under 4,000) this Dodecanese island is a pilgrimage site for Greek Orthodox because it is where John of Patmos received visions of the Book of

Breaking our voyage from Dubrovnik to Haifa was a stop at the island of Patmos. With the city of Chora (and a population under 4,000) this Dodecanese island is a pilgrimage site for Greek Orthodox because it is where John of Patmos received visions of the Book of

Revelations in a cave, and where he composed the Book of Revelations in the New Testament. The Monastery dates from 1088 and includes fortifications designed to thwart Turkish attacks on the island, though it fell to the Turks eventually (then to the Italians) and finally joined Greece in 1948.

Revelations in a cave, and where he composed the Book of Revelations in the New Testament. The Monastery dates from 1088 and includes fortifications designed to thwart Turkish attacks on the island, though it fell to the Turks eventually (then to the Italians) and finally joined Greece in 1948.

Author: Fred Hoyt

Ragusa

I was looking for Ragusa

July 25-26, 2012

My contribution to our vacation (yes, David, I did become Scoutmaster because I couldn’t dictate family vacations!) was the Adriatic coast; I had wanted to explore this battleground between East and West for a long time. Carolyn, by contrast, wanted the Egypt-Israel part of this cruise. So yesterday, Ragusa, was on my bucket list.

Justifiably so. If there’s anything better than being on the ocean or touring a fort, it’s touring a fort on the ocean. Only this fort encloses the old walled city of Ragusa. When it wasn’t enduring a major earthquake (1677) flattening the city, or substantial shelling from the Yugoslav army in 1991 (the “aggressors” our guide insisted), or under someone else’s rule (early, and after 1806, when it invited Napoleon’s troops in to prevent destruction of the city, which led to it becoming part of Austria after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, then part of Yugoslavia after the end of World War I, then part of Croatia after 1991), the city known then as Ragusa was an independent aristocratic republic ala Venice, which also claimed it for a time.

Justifiably so. If there’s anything better than being on the ocean or touring a fort, it’s touring a fort on the ocean. Only this fort encloses the old walled city of Ragusa. When it wasn’t enduring a major earthquake (1677) flattening the city, or substantial shelling from the Yugoslav army in 1991 (the “aggressors” our guide insisted), or under someone else’s rule (early, and after 1806, when it invited Napoleon’s troops in to prevent destruction of the city, which led to it becoming part of Austria after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, then part of Yugoslavia after the end of World War I, then part of Croatia after 1991), the city known then as Ragusa was an independent aristocratic republic ala Venice, which also claimed it for a time.

The result is a sun-baked old city that is under UNESCO protection for its quaint collection of buildings, relics, and above all, the wall. The city’s saint is Vlaho in Slavic, Blasius in Latin, which rather indicates we’re on the edge between the East and West, still Catholic, but with a nod to its Byzantine heritage, and a little to its Slavic ancestry as well.

The result is a sun-baked old city that is under UNESCO protection for its quaint collection of buildings, relics, and above all, the wall. The city’s saint is Vlaho in Slavic, Blasius in Latin, which rather indicates we’re on the edge between the East and West, still Catholic, but with a nod to its Byzantine heritage, and a little to its Slavic ancestry as well.

Three prominent sites were part of our tour—the Franciscan and Dominican chapels and monasteries, with one of the oldest pharmacies in Europe (the plagues and their aftermaths were the source of many of the churches in Europe) and the Cathedral with its relics—including gold-encased relics of St. Vlaho—his leg and arm. The star, however, was the city itself, and the prominent wall that surrounds the old city. The aqueduct system is a work of art as well, with world heritage reservoirs and fountains.

Three prominent sites were part of our tour—the Franciscan and Dominican chapels and monasteries, with one of the oldest pharmacies in Europe (the plagues and their aftermaths were the source of many of the churches in Europe) and the Cathedral with its relics—including gold-encased relics of St. Vlaho—his leg and arm. The star, however, was the city itself, and the prominent wall that surrounds the old city. The aqueduct system is a work of art as well, with world heritage reservoirs and fountains.

The only building on the main street from the glory days of the republic was a customs house; with a portico, it gave a hint of what the city must have looked like before the earthquake of 1677—Venetian. After the earthquake,  the other houses were rebuilt in a standard style, attractive, but without the frills of flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance period palaces. Interestingly, the old clock tower has a bell that rings on the hour—and three minutes later, giving a Mediterranean area comment on punctuality.

the other houses were rebuilt in a standard style, attractive, but without the frills of flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance period palaces. Interestingly, the old clock tower has a bell that rings on the hour—and three minutes later, giving a Mediterranean area comment on punctuality.

Ragusa’s claim to fame, though, was that it was a trading city, rather like Venice, but unlike Venice, sought to be neutral in war-torn Europe, rather like Switzerland with a fleet. Thus, the city had over 80 consulates at one time, and seems to have maintained good relations with Constantinople, even after that city fell into the hands of the Turks, a neutrality that lasted throughout the history of the Ragusa Republic (that is, until Napoleon ended its independence). It was the first “country” to recognize the independent United States.

If you are looking for Ragusa, you won’t find it on the maps today, though.  Its name now is Dubrovnik, the entrance on this cruise to a new world—Greece and the Middle East (or part of what was called the Orient). That’s one reason why, in our hour of free time, after circumnavigating the city on the wall, I ran back to catch the Jesuit Church—probably the last chance on this trip to view a Baroque church, and one that I was told was “the best Baroque church in town.” I am now Baroque!

Its name now is Dubrovnik, the entrance on this cruise to a new world—Greece and the Middle East (or part of what was called the Orient). That’s one reason why, in our hour of free time, after circumnavigating the city on the wall, I ran back to catch the Jesuit Church—probably the last chance on this trip to view a Baroque church, and one that I was told was “the best Baroque church in town.” I am now Baroque!

Venice was Sooo yesterday

July 24, 2012

I guess I’m fickle, since I found a new fancy today—an overnight sail to Ravenna and Bologna, and now I’m infatuated with those two Italian cities.

Bologna claimed my allegiance because it is the home of the first university in Europe—1088 was the origin of a school of anatomy and law (religion, apparently, was too serious to be left to the universities). Today, it houses 90,000 students, which is staggering in a city of 500,000. Fortunately, the school was in recess, so the traffic rather resembles Bloomington Normal in July—rather light. We exited the bus at the tombs

Bologna claimed my allegiance because it is the home of the first university in Europe—1088 was the origin of a school of anatomy and law (religion, apparently, was too serious to be left to the universities). Today, it houses 90,000 students, which is staggering in a city of 500,000. Fortunately, the school was in recess, so the traffic rather resembles Bloomington Normal in July—rather light. We exited the bus at the tombs

of the first three professors, which are impressive indeed, from the days when professors were esteemed. Furthermore, in the old library, faculty got to create and draw their own coat of arms, another European idea that would look pretty neat on the IWU campus—if we couldn’t build buildings that looked like they were from the 14th century!

of the first three professors, which are impressive indeed, from the days when professors were esteemed. Furthermore, in the old library, faculty got to create and draw their own coat of arms, another European idea that would look pretty neat on the IWU campus—if we couldn’t build buildings that looked like they were from the 14th century!

The most impressive building to me was an old castle, that after one of the many wars, became a palace with a new façade, constructed over two time periods, on one side. I never before realized the difference between Romanesque and Gothic (especially flaming Gothic) until I saw them side by side—rather plain, square, and ornate arches and circles over the windows.

One amusing and sort of frightening event. I was engrossed in the faulty  coat of arms, but saw that our tour director from the boat was equally absorbed. However, when we were ready to leave, we realized our guide had taken our group to the lunch stop. The Ukrainian tour director spoke no Italian, but we flagged down a police car. One of the officers had been born in New York (he said he was the only English speaker on the force). He called the boat, found out where our lunch was, and took us to the restaurant. Happily, I did not have to spend the rest of my life in Bologna.

coat of arms, but saw that our tour director from the boat was equally absorbed. However, when we were ready to leave, we realized our guide had taken our group to the lunch stop. The Ukrainian tour director spoke no Italian, but we flagged down a police car. One of the officers had been born in New York (he said he was the only English speaker on the force). He called the boat, found out where our lunch was, and took us to the restaurant. Happily, I did not have to spend the rest of my life in Bologna.

The other building worth going to Bologna to see is a massive cathedral, partially finished, in Gothic style, that the people of Bologna wanted to raise the money for themselves, and raised enough to start building the cathedral. They wanted it big, and it was so big that the Pope intervened and said that no church can be bigger than St. Peter. It was never finished, but the city’s residents have exhibited some liberal tendencies (it was a hub of the communist party after World War II, and there were some terrorist bombings in the 60s and 70s). The church is also renowned for a painting picturing Mohammed in hell, a picture which after 9/11 has the church under tight security (that along with the recent earthquake which closed a number of sites for repair).

The other building worth going to Bologna to see is a massive cathedral, partially finished, in Gothic style, that the people of Bologna wanted to raise the money for themselves, and raised enough to start building the cathedral. They wanted it big, and it was so big that the Pope intervened and said that no church can be bigger than St. Peter. It was never finished, but the city’s residents have exhibited some liberal tendencies (it was a hub of the communist party after World War II, and there were some terrorist bombings in the 60s and 70s). The church is also renowned for a painting picturing Mohammed in hell, a picture which after 9/11 has the church under tight security (that along with the recent earthquake which closed a number of sites for repair).

Bologna is around 60 miles inland from Ravenna, the city where our boat

was docked (actually, the city was on the Adriatic in Roman times, but the ocean had filled in, and it now sits 6 miles or so from the port). I was interested in Ravenna for its historical importance: after the split of the Roman Empire between Constantinople and Rome, the Romans eventually moved the capital to Ravenna, which was far easier to defend against the northern tribes. It was, in fact, the last capital of the Roman Empire. Theodoric I, an Ostrogoth, conquered the city and added

was docked (actually, the city was on the Adriatic in Roman times, but the ocean had filled in, and it now sits 6 miles or so from the port). I was interested in Ravenna for its historical importance: after the split of the Roman Empire between Constantinople and Rome, the Romans eventually moved the capital to Ravenna, which was far easier to defend against the northern tribes. It was, in fact, the last capital of the Roman Empire. Theodoric I, an Ostrogoth, conquered the city and added

something different to it: a form of Christianity that held Jesus was not one of the trinity, but the son of God. That sort of doctrinal challenge to Catholicism, branded Arianism, was banished at the Council of Nicea in the 4th century, but some of the sites in Ravenna managed to escape the order to destroy all Arian churches and mosaics.

something different to it: a form of Christianity that held Jesus was not one of the trinity, but the son of God. That sort of doctrinal challenge to Catholicism, branded Arianism, was banished at the Council of Nicea in the 4th century, but some of the sites in Ravenna managed to escape the order to destroy all Arian churches and mosaics.

The two (of eight) UNESCO sites we visited were not Arian, but had what art historians argue is the best preserved Byzantine icons. One set was in a church, where it portrayed the Byzantine Emperor who restored (Eastern) Roman rule, Justinian, and his wife, Theodora, whose accession from dancer to Empress scandalized the Christian world (The Empire became Christian when Constantine converted early in the 4th century). The bits of colored glass put together to depict Christianity, so characteristic of Byzantium, are among the best preserved in the world, and almost 8 centuries earlier than those in Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

How I wish I had spent more time in Ravenna than in Bologna, but at least I have seen both.

We’re at sea on our way to my next favorite—Dubrovnik.

Venice

July 24, 2012 Reminiscences from 2024

July 24, 2012 Reminiscences from 2024

I can see why visitors flock to Venice–to the point where the citizens of the Serene Republic have limited access to increasingly expensive housing, and have sought ways to reduce the number of visitors. Tour boats have been shunted to Trieste and other ports to take some of the pressure off Venice.

The city is certainly historic, scenic, and unique. Before commerce shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, Venice vied for leadership with other Italian city states. As party to the 4th Crusade in 1204, which

conquered and looted and ruled Byzantium, Venice acquired many artefacts from Constantinople, which now grace places like St. Mark’s in Venice.

conquered and looted and ruled Byzantium, Venice acquired many artefacts from Constantinople, which now grace places like St. Mark’s in Venice.

Two that come to mind are the four horses that graced the Hippodrome in Constantinople, and the Portrait of the Tetrarchs, celebrating Diocletian’s efforts to make the unruly Roman

empire manageable by dividing it into east and west and having assistants. Napoleon took the four horses to Paris as spoils of war, but the French returned them as part of the Vienna treaties, which ended the Napoleonic Wars–and the independence of Venice. There are, however, over 800 items in the Treasury in St. Mark’s Cathedral that were further east before the 13th century.

empire manageable by dividing it into east and west and having assistants. Napoleon took the four horses to Paris as spoils of war, but the French returned them as part of the Vienna treaties, which ended the Napoleonic Wars–and the independence of Venice. There are, however, over 800 items in the Treasury in St. Mark’s Cathedral that were further east before the 13th century.

Set in a lagoon on land that is apparently sinking, Venice is a pastiche of colors, churches, and palaces, best accessed on foot or by boat. No trip to the city is complete without a gondola ride–and even our hotel had a boat entrance.

Set in a lagoon on land that is apparently sinking, Venice is a pastiche of colors, churches, and palaces, best accessed on foot or by boat. No trip to the city is complete without a gondola ride–and even our hotel had a boat entrance.

The city also housed the first ghetto in Europe, remnants of which are still extant.

The city also housed the first ghetto in Europe, remnants of which are still extant.

What I loved about the city is that it’s a wonderful place to wander. You’d spot some intriguing doorway, open it, be treated to baroque artwork, and wonder why it wasn’t in the Lonely Planet. I finally realized if the Lonely Planet listed

everything worth seeing in Venice, it would be in a book that filled the Library of Congress. With the waterways, too, I couldn’t go too far in any direction. If you wanted to go somewhere else, such as Murano, home of famous glass blowing, you had to take a water taxi. No wonder the bridge got a lot of foot traffic!

everything worth seeing in Venice, it would be in a book that filled the Library of Congress. With the waterways, too, I couldn’t go too far in any direction. If you wanted to go somewhere else, such as Murano, home of famous glass blowing, you had to take a water taxi. No wonder the bridge got a lot of foot traffic!

Epilogue on returning home

I arrived in Bloomington 24 hours ago, happily (using air miles) via First Class on American. It seemed a fitting way to end a First Class journey around the world—after a 6 hour train from Datong to Beijing.

There were two newsworthy articles this morning in the Wall Street Journal relevant to the trip. One was the slowdown in India (based partly on the slowdown elsewhere in the world), and the slowdown in China. You definitely have to read the non-Chinese press in particular to get that impression, though between the lines, you can tell there are some cracks in the picture of progress China presents.

The Chinese government vocabulary emphasizes the need for social stability; its contract is continued power in return for generating continued prosperity—even if that means stimulating the economy through an economic package that tends to favor domestic consumption.

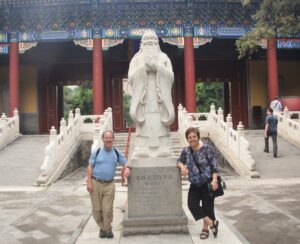

The emphasis on social stability was visible in at least two places where one might not have expected it. The first was in the Confucian temple in Beijing. We got there in time to see a dance performance based on the teachings of Confucius. Part of the message was about “social stability.” The Chinese phrase was, “Tian xia wei gong,” one of the teachings of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, roughly translated as “The Earth Belongs to the People.” You can find that on the gateway to almost every Chinatown in the United States (see Chicago’s, if you

The emphasis on social stability was visible in at least two places where one might not have expected it. The first was in the Confucian temple in Beijing. We got there in time to see a dance performance based on the teachings of Confucius. Part of the message was about “social stability.” The Chinese phrase was, “Tian xia wei gong,” one of the teachings of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, roughly translated as “The Earth Belongs to the People.” You can find that on the gateway to almost every Chinatown in the United States (see Chicago’s, if you doubt me). That Confucius is revered today is a remarkable change from the Mao past, when the “New China” meant demolishing the old.

doubt me). That Confucius is revered today is a remarkable change from the Mao past, when the “New China” meant demolishing the old.

The second clue is the “Beijing Spirit” motto: “Patriotism, Innovation, Inclusiveness, and Virtue.” The last named is also part of the Confucian ethic.

The second clue is the “Beijing Spirit” motto: “Patriotism, Innovation, Inclusiveness, and Virtue.” The last named is also part of the Confucian ethic.

The “New New China” with its emphasis on the “New Old” indicates to me that Mao in remaking China missed some of the good in the old. What sounds like thunder in China, in other words, is really Mao turning in his grave.

And so the adventure ends–and I’m ready for the next one!

Reminiscence 2025. Hard to believe, but this was my last brush with Asia. I wonder how much has changed, especially after COVID.

Tourism in Datong — of all places

Guess what?

On the way in to Datong, my guide pointed out the new buildings on the far side of the river, which included the government center, apartment buildings, and so forth. She noted that the government decided to move away from the older area of the city to foster tourism, and prepare for the day when the coal mines, the backbone of the local economy, give out. Somebody must be reading my blog!

The question I had, however, was—what does Datong have that would attract tourists? Of course, it has (like everywhere in China), at least 2,000 years of history, but what’s left? And what will attract people to come here? That was the quest for today.

My conclusion is that if it’s your first trip to China, and you have two or three weeks, Datong is not likely to be on your list. But in the name of fairness, let me tell you about the attractions of the city and area, which, if it doesn’t sway you to put Datong on that first trip list, might encourage a visit sometime; bear in mind, it took 22 years of China visits before I found my way here. After all, it has a well-known coal mine museum (which I skipped), and used to build locomotives (and thus had a locomotive museum for a long time—it’s now in Beijing.)

Datong historically has had two brief flirtations with fame, both involving dynasties beyond the wall. The first was the Northern Wei dynasty, which

for nearly a hundred years made Datong its capital. Notice, the brief flirtation can last 100 years. Part of that imperial presence led to probably Datong’s greatest attraction (unless you’re a coal mine devotee),which are the Yungang caves. With about 51,000 statues in 49 grottoes, the sheer number alone should be reason to visit this world heritage site. In addition, the statues were carved in sandstone, so erosion has been a problem that the Chinese government has addressed

for nearly a hundred years made Datong its capital. Notice, the brief flirtation can last 100 years. Part of that imperial presence led to probably Datong’s greatest attraction (unless you’re a coal mine devotee),which are the Yungang caves. With about 51,000 statues in 49 grottoes, the sheer number alone should be reason to visit this world heritage site. In addition, the statues were carved in sandstone, so erosion has been a problem that the Chinese government has addressed

partly by enclosing the most attractive treasures (and that not so coincidentally keeps the coal smoke out). The big statues (some are 60 feet high) are stunning, some of them with the original colors. My guide pointed out that in this early period the Buddhas still had Indian characteristics, though some of the “two Buddha caves” had Buddha heads that looked suspiciously like the Northern Wei emperor and his mom, under whose sponsorship the caves were built; one large statue was carved honoring one of the Wei emperors who tried to eradicate Buddhism—posthumously, of course. With the move to Luoyang in 492, the cave carving petered out, and eventually stopped. We visited 20 of the 49 grottoes; I went on to another 19, and there was only one where I stopped to take a picture.

partly by enclosing the most attractive treasures (and that not so coincidentally keeps the coal smoke out). The big statues (some are 60 feet high) are stunning, some of them with the original colors. My guide pointed out that in this early period the Buddhas still had Indian characteristics, though some of the “two Buddha caves” had Buddha heads that looked suspiciously like the Northern Wei emperor and his mom, under whose sponsorship the caves were built; one large statue was carved honoring one of the Wei emperors who tried to eradicate Buddhism—posthumously, of course. With the move to Luoyang in 492, the cave carving petered out, and eventually stopped. We visited 20 of the 49 grottoes; I went on to another 19, and there was only one where I stopped to take a picture.

From the sublime to “over the top.” In line with the “creation” of a tourist

base, the Datong government has recreated a “Northern Wei” palace that has buildings and figures resembling those in the caves, and a “new old” city on the way out, full of merchants offering mostly the same merchandise you see everywhere in China. It is becoming a pattern in China. Get ’em in and keep ’em shopping. I was the only westerner there this morning.

The second flirtation with fame that redounds to Datong’s reputation was the Liao period, the 12th century, when Datong was a first-tier second-tier city, below the capital. It enjoyed imperial blessing again, which led to serious

temple building, with a very distinctive art form. Many of the buildings have been destroyed over the years, but a restoration under the Ming/Qing rulers kept some of them intact—and since the 1990s, many more have been reconstructed. Sometimes it is difficult to tell the difference between the old and the “new old.”

temple building, with a very distinctive art form. Many of the buildings have been destroyed over the years, but a restoration under the Ming/Qing rulers kept some of them intact—and since the 1990s, many more have been reconstructed. Sometimes it is difficult to tell the difference between the old and the “new old.”

The third claim to fame is based on its location. As my guide proudly stated, Datong is the only major Chinese city between the Great Wall to keep the northern barbarians out and the inner wall to keep the Chinese in. As a border station, it was important in the Han dynasty (there is a portion of the Han Great Wall here) and the Ming Great Wall (which is in the process of being rebuilt). In fact, there is a major effort by the new mayor to create a new old city, which is already underway. There is a nine-dragon wall that used to be in front of the Ming governor’s palace in the early Ming

period.

period.

The governor could have a dragon wall because he was the thirteenth son of the Emperor. The wall was moved to a former temple when the palace was torn down years ago, but the wooden frame of its replacement is underway, in a swath of buildings cleared to make the “new old” city.

The new mayor might not have said, “If you build it, they will come,” but he is banking Datong’s future on its past.

Have you moved it higher on your bucket list?

Better than Magnificent

Words failed Li Bing when he saw the last temple I saw today. The famous Tang poet could only inscribe “magnificent” on a rock, but added a dot after zhuang guan, an exclamation point in a language that has none.

He might have been thinking about the kind of day I had, which began when we left Pingyao for the 250 or so mile trip to Datong, one that was literally a high (8,000 feet). The first stop should have been the clue—one of the four sacred Buddhist mountains: Wutaishan rises to 2100 meters and has five peaks (hence the name; wu means five). Here’s what I remember:

-The first temple (we visited it) began shortly after the introduction of Buddhism into China from India, around 70 A.D. Subsequent temples pushed the total up into the hundreds, though today there are only 47. To see them all, my guide suggested, would take half a month.

-The first temple (we visited it) began shortly after the introduction of Buddhism into China from India, around 70 A.D. Subsequent temples pushed the total up into the hundreds, though today there are only 47. To see them all, my guide suggested, would take half a month.

-“base camp” is over a mile high, providing a cool environment in the summer.

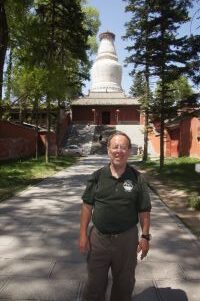

-one of the temples has a white dagoba, an Indian-shaped pagoda that looks something like a bowling pin. Reputedly, it is the largest in China. The signpost said that it was originally built with the help of the great Indian King, Asoka, but I don’t think the timing works. It was enlarged later, and is reputed to hold relics of the Lord Buddha.

-one of the temples has a white dagoba, an Indian-shaped pagoda that looks something like a bowling pin. Reputedly, it is the largest in China. The signpost said that it was originally built with the help of the great Indian King, Asoka, but I don’t think the timing works. It was enlarged later, and is reputed to hold relics of the Lord Buddha.

-a temple built in 1921 has the largest marble arch in China. (everything is largest something or another)

-with the eminent Buddhists of the Qing dynasty claiming to have been descended from the Buddha disciple Manjuri (based on the similarity in the pronunciation of the Manchus), they took a fondness to the site because the temples are dedicated to Manjuri (from what my guide said, each of the famous Buddhist mountains is dedicated to one of the major Bodhisattvas). And given the fondness of the Qing for the Tibetan Lama Buddhism, it  is no surprise that the temples have a lama orientation, some markedly so.

is no surprise that the temples have a lama orientation, some markedly so.

The one we visited had been sequestered by Kangxi, who came five times, and because he turned it into a royal temple, it has a gold roof, and the largest wooden archway in Wutaishan. It also has 108 stairs, which is a solemn number in Buddhism, and a good number for me, because we were going down it. There were a number of steles with poetry or inscriptions by Kangxi and Qianlong, who seemed to have visited a lot of places in their 120 years of rule, and left lots of stone steles.

Our next stop on the ride to Datong was a wooden pagoda, but not just a wooden pagoda—the tallest in China. It dates from the short-lived Liao dynasty (somewhere in the 1100s), and also contains relics (i.e., body pieces) from the Lord Buddha. The Buddha is Liao style—with a green beard and moustache since the Liao, a people from north of the wall (i.e., barbarians) had mustaches, and, therefore, the Buddha would have to as well. Furthermore, the moustache beard was green because the Liao believed green was a sacred color. At least that’s what I was informed. I told you Buddhism allowed local adaptations!

That the pagoda was in the small town it was because the emperor’s mother came from there, and she was a devout Buddhist. That the pagoda exists is due to its ability to survive two catastrophes in China:

That the pagoda was in the small town it was because the emperor’s mother came from there, and she was a devout Buddhist. That the pagoda exists is due to its ability to survive two catastrophes in China:

1) An earthquake in the late Qing dynasty leveled the rest of the temple, but the tower survived because, being made of wood, it was flexible. As might be expected, a reconstruction of the temple is underway in the name of tourism.

2) The Cultural Revolution. Parts of the Buddha were hacked, and some documents which had been hidden in it were destroyed, including much of the history of the temple.

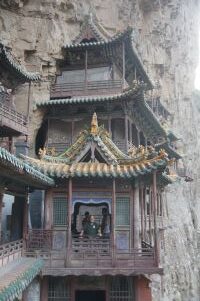

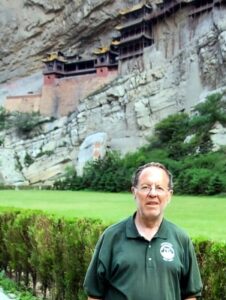

The last stop was the one Li Bing, a thousand years ago, called “magnificent “—the hanging temple on Hengshan, another sacred mountain, this one to Daoism. Begun in the Song dynasty (or earlier), the temple looks like it ought to have a frame around it, and be sold as a 3 D insert; it literally clings to the side of a mountain. It was built by monks who perched down from the top, put in beams, carved the caves, etc. It is a Daoist temple—but at least one room helps explain why it (and

The last stop was the one Li Bing, a thousand years ago, called “magnificent “—the hanging temple on Hengshan, another sacred mountain, this one to Daoism. Begun in the Song dynasty (or earlier), the temple looks like it ought to have a frame around it, and be sold as a 3 D insert; it literally clings to the side of a mountain. It was built by monks who perched down from the top, put in beams, carved the caves, etc. It is a Daoist temple—but at least one room helps explain why it (and  not much else on Hengshan) survived the Cultural (and other) Revolution. One multicultural (my word, not the guide’s) room has: the Buddha in the center, one of the Daoist immortals on one side, and Confucius himself on the other. Rumor has it that one tablet was added during the Cultural Revolution—“Long Live Chairman Mao.” And that may well be why the Hanging Temple (truly magnificent, and fortunately, we do have an exclamation point in English!) exists today. Period.

not much else on Hengshan) survived the Cultural (and other) Revolution. One multicultural (my word, not the guide’s) room has: the Buddha in the center, one of the Daoist immortals on one side, and Confucius himself on the other. Rumor has it that one tablet was added during the Cultural Revolution—“Long Live Chairman Mao.” And that may well be why the Hanging Temple (truly magnificent, and fortunately, we do have an exclamation point in English!) exists today. Period.

As I said, a magnificent day.

Pingyao 2

If you were looking for a city built to be a caricature of a “Chinese” city, you wouldn’t have to look far, at least not if you were in Pingyao, a world heritage UNESCO city of nearly 50,000 people in Shanxi province. Unlike the similarly-positioned Lijiang, in Yunnan, far from here, which had to be partially reconstructed after an earthquake, Pingyao, for all practical purposes, looks rather like the city it has been since 1370, when the Ming moved it a few kilometers and enclosed the city in a stately wall that still surrounds the “ancient” city.

It has what you’d need to make it into a tourist destination–quaint Ming and Qing dynasty houses easily turned into ambient guest houses and restaurants and small shops.

It has what you’d need to make it into a tourist destination–quaint Ming and Qing dynasty houses easily turned into ambient guest houses and restaurants and small shops.

Our day began with a made-for-tourist celebration that consisted of young ladies on parade dressed in Qing costumes, imitating women with bound feet (some emperor liked it, so for centuries rich women broke the toes of their daughters to make them more attractive—only peasant women had regular-sized feet). The practice was not banned until the 20th century. The ladies were followed by jugglers, and the festivities culminated in a processional for the governor and his entourage.

We then walked along the wall, originally built in 1372, and relatively intact  since then. It is about 6 miles long, but nowhere near as wide as the one in Xi’an. Most of the buildings in it are Ming/Qing, with some more recently built. There was one factory which the government evicted, and, as our guide noted, some of the land was given to developers for hotels, etc. Tourism, as I have been saying this whole trip, is the world’s biggest business, and China has some of the best infrastructure in the world for the business. It is a big revenue generator. Ticket prices for attractions have gone up greatly; the city tour package is over 30$ US. The government is now developing the tourist trade for domestic Chinese. I am one of the few non-backpacking Americans here, and there was a BIG crowd this weekend. The guides have taken to using megaphones, even for groups of 3 or 4, which makes some places impossibly noisy. One year I saw there were 15 million tourists!

since then. It is about 6 miles long, but nowhere near as wide as the one in Xi’an. Most of the buildings in it are Ming/Qing, with some more recently built. There was one factory which the government evicted, and, as our guide noted, some of the land was given to developers for hotels, etc. Tourism, as I have been saying this whole trip, is the world’s biggest business, and China has some of the best infrastructure in the world for the business. It is a big revenue generator. Ticket prices for attractions have gone up greatly; the city tour package is over 30$ US. The government is now developing the tourist trade for domestic Chinese. I am one of the few non-backpacking Americans here, and there was a BIG crowd this weekend. The guides have taken to using megaphones, even for groups of 3 or 4, which makes some places impossibly noisy. One year I saw there were 15 million tourists!

Among other visits in the city was one to China’s first bank, here in Pingyao in 1823. It handled bank transfers in over 20 cities, including Calcutta in India and Kowloon in Hong Kong, and lasted until the 1930s or so. It sounded like the Hanseatic League, with “internships” for young Chinese more interested in commerce (and wealth) than in government and Chinese classics. At one time, 90% of China’s banking service was done by Shanxi financiers, and much of that in Pingyao.

If you were looking for temples, this had some 4 star attractions. One, close to the city, and named for an episode in the life of the Buddha, had some statues that date back to the Song dynasty, or almost 1000 years ago. Some  of the statues retained their original colors, and the 1000 armed Guan Yin, the goddess of mercy (who in the process of moving from India to China became more feminine than masculine) is particularly striking.

of the statues retained their original colors, and the 1000 armed Guan Yin, the goddess of mercy (who in the process of moving from India to China became more feminine than masculine) is particularly striking.

In addition to the Buddhist temples, there was a city god temple, a Daoist celebration reconstructed during the reign of Qianlong, with a statue to the Guan Gong, my candidate to replace Tommy Titan. The Guan Gong is celebrated as the God of Wealth and the God of War, the former of which puts him pretty high in today’s Chinese pantheon (socialism with Daoist characteristics?).

former of which puts him pretty high in today’s Chinese pantheon (socialism with Daoist characteristics?).

Across from that, there is a Confucian temple that purports to be one of the best still extant in China (Confucius came in for a battering during the Cultural Revolution, as one of the “olds,” but I’ll have more to say about its revival before I leave China). There are some nice exhibits on the Confucian exams in the temple, which was one of the most serene places in the city.

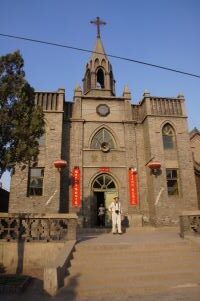

There

are even two Christian churches from the early 20th century, one Catholic, one Protestant, which I understand are packed on Sundays.

are even two Christian churches from the early 20th century, one Catholic, one Protestant, which I understand are packed on Sundays.

The other striking public building is the home of the governor, which is residence, administrative offices, and jail—all in one place. The striking thing was the jail and prison, partly because in criminal court cases, the plaintiff and defendants both knelt down in a specific spot before the judge, who could use torture (the tools of the trade were there, including knuckle busters) to extract confessions. A red-colored piece of wood signified death, and we saw, in the prison, the various forms of punishment, which ranged from public humiliation to beheading, to the “death by 1000 cuts,” which consisted of having your body wrapped in a fishnet, squeezed, and the skin that protruded sliced.

I said this is the ideal model for what foreigners (and Chinese) think is a model Ming/Qing city. I’ve been to others which have rebuilt areas like this—I think it was Kaifeng or Luoyang, former capitals. I know Xi’an has an area near the south wall that has a reconstructed “antique street” that is no more antique than the last four or five years. The difference is that Pingyao has an antique street that is an antique, and limits cars to the edges of the old walled city. It is a model—but it is an original, not a copy

My adventure begins in Pingyao

In effect, the class ended when we arrived back in Beijing on Friday. We all had a free afternoon and evening to do last minute things—whether it was visit the zoo to see pandas, the pearl market to buy copies or real pearls, or to sample the night life (my recommendation was the Banana club. “did you like it Hoyt?” “No, but that means you will.”)

I did a few things I wanted to do. I went out for lunch with our guide, who asked whether I had ever eaten donkey, which he said was a Beijing specialty. Check that off my list of things to do. He said he’d had only one other tour leader sample the dish, and that person was lukewarm. I’d do it again—especially if any of those burros at Philmont give me a hard time.

We were near Liulizhang, which used to be the scholar/artist street. It’s still quaint, but in the current effort to build tourism, is a mix of older buildings built to look old, and older buildings that are. I stopped in to the tea shop I’ve frequented for seven years, the owner reminded me, and asked about my former student, JR Glenn, who has been there with me several times. I couldn’t leave without buying my favorite tea, liqi hong, a black tea flavored with lichee. I have never found it in the United States.

There was one other place on my itinerary—the Summer Palace built by

Qianlong that was destroyed in 1860; I had been there only once. It’s on the outskirts of the city, but Beijing is fairly easy to navigate (thank you 2008 Olympics!) with 14 lines and a 30 cent fee for busses or subways. The buildings were mostly European style, and made of stone. The rubble remains as a haunting reminder of what happened to China during its century of humiliation. There were lakes as well, a legacy of Kangxi’s trips to the South, and especially the storied gardens of Suzhou and Hangzhou, which shaped the construction of the summer villa we saw at Chengde.

For a last meal with my colleague Ruth Ann, we went to nearby Wangfujing street, the “Michigan Avenue” of China. Passing through food street with its vendors selling everything from scorpion on a stick to dumplings, passing the old Catholic church, rebuilt after being destroyed by the Boxers (where a large crowd had gathered doing line dancing on Friday night), we went to Quanjude, the largest roast duck chain in the city. The hotel recommended it, and responded in the positive when I asked whether Chinese ate there (or whether it was primarily a tourist attraction). Beijing does attract tourists, Chinese and foreign, but we were the only Westerners in the restaurant.

At 4:30 am, I bade farewell to my 14 traveling companions, as they boarded the bus to the airport.

And my adventure alone began. I got a bullet train to Taiyuan. It’s around 300 miles southwest of Beijing—and it took 4 hours to get there. For those of you who have been on Chinese trains, you should be astonished—the ordinary train takes 8 hours. The cost was around $25!

Taiyuan is not a tourist destination, being an old city that has more history than historical artifacts, and is currently a center of heavy industry. We did

see two interesting sites, nonetheless. One was a temple dedicated to a general, which had a 3200 year old tree, and some unusual construction including a cross bridge, with a Daoist half and a Buddhist half. The other was the home of a rich family that had business scruples (Confucian in origin, like treating  people fairly) and moral scruples (no concubines), and lasted as a wealthy family for five generations.

people fairly) and moral scruples (no concubines), and lasted as a wealthy family for five generations.

The compounds (two generations added to the construction, and included a stage for performing Shanxi opera) have been turned into a museum to showcase local customs and art, as well as to tell the story of the Qiao family. The wealth initially came from making bean curd (tofu), and wound up as banking/trading operation with locations all over China (except Gansu and Yunnan, I believe). The family housed Cixi when she fled Beijing after the 8 armies suppressed the Boxers, and she gave

wealth initially came from making bean curd (tofu), and wound up as banking/trading operation with locations all over China (except Gansu and Yunnan, I believe). The family housed Cixi when she fled Beijing after the 8 armies suppressed the Boxers, and she gave  them presents in return, including the right to call the house the best courtyard in China (sounds like something the Chamber of Commerce would designate); they gave her a month lodging, 300000 tales of silver, and apparently greased the wheels of the successors, which kept the house intact until the family fled the Japanese in 1937.

them presents in return, including the right to call the house the best courtyard in China (sounds like something the Chamber of Commerce would designate); they gave her a month lodging, 300000 tales of silver, and apparently greased the wheels of the successors, which kept the house intact until the family fled the Japanese in 1937.

Rather than stay in Taiyuan, my guide took me to Pingyao for two evenings, and that’s a different blog and a very different experience. I’ll send this when I can. Pingyao is an “ancient city” surrounded by a Ming dynasty wall, and minimum amenities. I’d say it’s like Lijiang in Yunnan, but none of you have been there, so I’ll tell you about it after I’ve toured it.

From Ming to Qing

We were in Chengde, 130 miles or so north of Beijing. It’s about 15 degrees cooler, 1500 feet higher, and has about 23 million fewer inhabitants. We’ve gone back to China about 10 years ago, maybe more, but it does boast a McDonalds and a KFC franchise. It is pleasant to visit a smaller city, if only for the slower pace and the smaller crowds!

Having spent yesterday in the Yongle mode of the 15th century, we’ve gone ahead in some ways into Qing period, from 1644 till 1911. The last stop we had in Beijing belonged to that period—the famous Summer Palace built by the infamous Empress Dowager, Cixi, who was the mastermind behind

China from 1861 until her death in 1908. She kept her position mostly through guile, with a dash of poison—several emperors for whom she served as regent died mysteriously.

The 1881 Summer Palace, one of the must sees in Beijing is her  legacy. She constructed it northwest of Beijing (which has grown to absorb it) to replace the Yuan Ming Yuan, a summer palace reputedly one of the wonders of the world, which the allied armies, who torched Beijing in 1860, left in ruins. Those ruins today rest nearby, and if I have time on our return to Beijing, I hope to get out there. They are hauntingly part of the “road to rejuvenation,” the exhibit I saw this morning at the National Museum of China, a stupendous building that is so big it seems relatively empty of artefacts, although I suspect there were thousands. A separate exhibit that is difficult to find deals with the road to rejuvenation, the route the Communist Party traveled in undoing

legacy. She constructed it northwest of Beijing (which has grown to absorb it) to replace the Yuan Ming Yuan, a summer palace reputedly one of the wonders of the world, which the allied armies, who torched Beijing in 1860, left in ruins. Those ruins today rest nearby, and if I have time on our return to Beijing, I hope to get out there. They are hauntingly part of the “road to rejuvenation,” the exhibit I saw this morning at the National Museum of China, a stupendous building that is so big it seems relatively empty of artefacts, although I suspect there were thousands. A separate exhibit that is difficult to find deals with the road to rejuvenation, the route the Communist Party traveled in undoing  the century of humiliation. Some of the pictures in that exhibit (the captions were mostly in Chinese, but it’s the Chinese vocabulary I learned in the early 1970s of revolution and imperialism; my favorite was a pamphlet by renown missionary Young J. Allen extolling British imperialism in India) showed foreign troops ransacking that palace and sitting on the imperial throne. And they got a medal for it!

the century of humiliation. Some of the pictures in that exhibit (the captions were mostly in Chinese, but it’s the Chinese vocabulary I learned in the early 1970s of revolution and imperialism; my favorite was a pamphlet by renown missionary Young J. Allen extolling British imperialism in India) showed foreign troops ransacking that palace and sitting on the imperial throne. And they got a medal for it!

The new summer palace demonstrated that the Qings could spend money on themselves, building halls, lakes, islands, Buddhist temples, and what the Guinness Book of Records says is the largest painted corridor in the world, with hand-painted illustrations from Chinese literature on the arches that support this covered walkway. The courtyard in front of the Empress Dowager’s bedroom contains the phoenix (symbol of the Empress) in the place of honor, exchanging places with the dragon (symbol of the Emperor), more accurately reflecting power in Ci xi’s empire than the titles. It also contains the largest single rock in China used for display.

The route to Chengde, a superhighway with relatively little traffic, and a view and access to still another reconstructed section of the Great Wall, one where you can do a five-mile hike, demonstrates epigrammatically the difference between the infrastructure in China and India; we arrived quickly, and not having felt we’d spent the ride in a washing machine.

Chengde’s reputation and attraction as a tourist site (the province is striving to make it an international tourist city) rests on the legacy of two Qing emperors—Kangxi and Qianlong. Imagine if US history had been dominated for 120 years by two presidents, and you get an idea of what those two men meant to China from the late 1600s until almost the 18th century. Kangxi ruled for 61 years as emperor, and according to a show (more about that) we saw tonight, helped transform the Manchus from north of the Great Wall barbarians into—what else—civilized Chinese, scholars respectful of Chinese language, history, traditions, and the religions (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism). Both had an understandable orientation to the north, being related to the Tibetans and Mongolians, and being wary of the other barbarians north of the wall.

Chengde’s reputation and attraction as a tourist site (the province is striving to make it an international tourist city) rests on the legacy of two Qing emperors—Kangxi and Qianlong. Imagine if US history had been dominated for 120 years by two presidents, and you get an idea of what those two men meant to China from the late 1600s until almost the 18th century. Kangxi ruled for 61 years as emperor, and according to a show (more about that) we saw tonight, helped transform the Manchus from north of the Great Wall barbarians into—what else—civilized Chinese, scholars respectful of Chinese language, history, traditions, and the religions (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism). Both had an understandable orientation to the north, being related to the Tibetans and Mongolians, and being wary of the other barbarians north of the wall.

Partly to keep those barbarians in check, and partly because the temperature in Chengde is more temperate, and partly because the north afforded the grasslands that warriors on horseback needed to hone their skills, Kangxi established a mountain summer villa here, a predecessor to the summer palace we saw in Beijing, and five times as large as the

Forbidden City. It contains three artificial lakes, bedrooms and meeting rooms (the ruling family moved here for six months a year) and conducted the affairs of state here; probably the most famous encounter was with the English emissary, Lord McCartney, who sought to open relations with China in 1793. Qianlong essentially told the Englishman that China had everything it needed, thank you; and McCartney refused to bow to the Emperor and perform the rituals that the Asian states had done with China. China’s relations with the rest of Asia had been as a superior to vassals, and the attitude of superiority still colors China’s view of the world. It is a striking place that reflects the power and wealth of the Manchus. As I pointed out to my class, the combination of overwhelming ego and overwhelming wealth and overwhelming power were overwhelming. (One of my students noted that if that was what was required to be an emperor, I had at least one of those attributes).

Forbidden City. It contains three artificial lakes, bedrooms and meeting rooms (the ruling family moved here for six months a year) and conducted the affairs of state here; probably the most famous encounter was with the English emissary, Lord McCartney, who sought to open relations with China in 1793. Qianlong essentially told the Englishman that China had everything it needed, thank you; and McCartney refused to bow to the Emperor and perform the rituals that the Asian states had done with China. China’s relations with the rest of Asia had been as a superior to vassals, and the attitude of superiority still colors China’s view of the world. It is a striking place that reflects the power and wealth of the Manchus. As I pointed out to my class, the combination of overwhelming ego and overwhelming wealth and overwhelming power were overwhelming. (One of my students noted that if that was what was required to be an emperor, I had at least one of those attributes).

The area is dotted with temples built by the royal family, and we visited two

of them, both built by the reverent Buddhist, Qianlong. One was to make his northern guests feel at home, and looks rather like the Potala Palace in Lhasa, which would make the Dalai Lama, the head of Tibetan Buddhism feel comfortable, but as our guide pointed out, there were subtle hints that while the Dalai Lama was a friend, the Emperor was still the boss. Some of

of them, both built by the reverent Buddhist, Qianlong. One was to make his northern guests feel at home, and looks rather like the Potala Palace in Lhasa, which would make the Dalai Lama, the head of Tibetan Buddhism feel comfortable, but as our guide pointed out, there were subtle hints that while the Dalai Lama was a friend, the Emperor was still the boss. Some of  the hints were not so subtle, such as the Chinese style roofs atop the Tibetan style buildings, but then, in Lhasa, there’s a plaque to one of the first treaties signed with Tibet, in which the Chinese stated they were the “big brother;” that’s been the attitude toward Tibet ever since.

the hints were not so subtle, such as the Chinese style roofs atop the Tibetan style buildings, but then, in Lhasa, there’s a plaque to one of the first treaties signed with Tibet, in which the Chinese stated they were the “big brother;” that’s been the attitude toward Tibet ever since.

This evening we visited the new new China’s view of the Kangxi period—a show developed by the film studio that developed the Olympic opening show. It was another over-the-top tourist attraction (exceeding, by far, the sedan chairs that tourists can now ride!), with 300 horses and 600 actors,  and animation you would not believe. Having been here, though, I can believe it. One of the messages in it was that Kangxi recovered Taiwan, which held out against the Qing until the 1680. On the other hand, Qing fortune in the 1680s also brushed up against the aggressive Russian state, then moving into Asia. The Treaty of Nerchinsk, between the Qing and the Romanovs was one of the first modern treaties, an opening step that would eventually help make the Ming and Qing part of what the Chinese like to call their “feudal past.”

and animation you would not believe. Having been here, though, I can believe it. One of the messages in it was that Kangxi recovered Taiwan, which held out against the Qing until the 1680. On the other hand, Qing fortune in the 1680s also brushed up against the aggressive Russian state, then moving into Asia. The Treaty of Nerchinsk, between the Qing and the Romanovs was one of the first modern treaties, an opening step that would eventually help make the Ming and Qing part of what the Chinese like to call their “feudal past.”