August 11, 2013

The road to Rhodes

We’re at the last stop on our vacation, the Island of Rhodes. I’ll have more to say about it tomorrow (we arrived late this afternoon, and are staying in a boutique hotel in the “old town”), but I wanted to say a few more words about Thessaloniki.

Yesterday (seems longer ago), we took a boat tour to Mount Athos, with 20 Orthodox monasteries, one of the largest religious concentrations this side of Tibet. I almost said we went to Mount Athos, but that semi-state has tighter security than North Korea. For one thing, half of mankind (women) is excluded. The founding myth of the peninsula is that the Virgin Mary set  foot on it, and the monks have decided no woman can top her—despite some EU efforts to open it up. After all, the Byzantine emperor ruled in 1050 or thereabouts that only men would be allowed on Mount Athos, and his writ still stands. Indeed, the monks follow the Julian calendar, the last holdouts anywhere in the world. Byzantium is still reasonably alive on Mount Athos. For another, the community accepts only 100 Orthodox visitors and 10 non-Orthodox a day, in a process of selection that can take months. You can stay for three nights, if chosen.

foot on it, and the monks have decided no woman can top her—despite some EU efforts to open it up. After all, the Byzantine emperor ruled in 1050 or thereabouts that only men would be allowed on Mount Athos, and his writ still stands. Indeed, the monks follow the Julian calendar, the last holdouts anywhere in the world. Byzantium is still reasonably alive on Mount Athos. For another, the community accepts only 100 Orthodox visitors and 10 non-Orthodox a day, in a process of selection that can take months. You can stay for three nights, if chosen.

The alternative for us was a boat trip that skirted one side of the peninsula, from which we could see I think it was nine of the monasteries. Some clung to the sides of the cliffs (Mount Athos itself is almost 6500 feet, rising abruptly from sea level!) and look like the hanging temple I saw in China  last year; others have elaborate layouts that look like they ought to be in Russia, with the onion domes (actually, that was the Russian monastery). The monasteries, built as early as the 9th century, possess some incredible relics that were on display in a special exhibit in the Thessaloniki museum

last year; others have elaborate layouts that look like they ought to be in Russia, with the onion domes (actually, that was the Russian monastery). The monasteries, built as early as the 9th century, possess some incredible relics that were on display in a special exhibit in the Thessaloniki museum

I would be remiss if I did not point out that the seafood has been especially good in Greece. We had a wonderful meal courtesy of George Kambroulogou and his wife; IWU gave me his name when I asked for alums in Europe, and though George (class of 93) only knew me by reputation (he was kind), he generously welcomed us to Brussels, where he works for the EU. When he heard I was going to be in Thessaloniki, his home town, he told me he’d take us out to dinner since he was going to be there when he was on vacation. George might have taken a Chinese philosophy class at IWU, since he embraced the Confucius saying, “It is a pleasure to welcome guests who come from afar.”

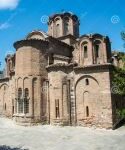

Because our plane was at 2 this afternoon, I had a free morning, and with a free bike, I resolved to either revisit some places, or go to see sights we could not get near because of parking problems or lack of time. Sunday morning seems to be an excellent time to explore cities, and bikes are a great way to cover a lot of distance reasonably quickly. In addition, the churches had services, so the churches were used as churches should be. I spent some time at the palace of Galerius, the Roman agora (marketplace), the great walls constructed initially by Theodosius, Hagia Sophia and another church that still bore an inscription boasting that the Sultan had taken it from infidels—along with a nice ride along the Thermatic Gulf.

another church that still bore an inscription boasting that the Sultan had taken it from infidels—along with a nice ride along the Thermatic Gulf.

Five hours later, we were in Rhodes, in the old town, which between 1309 until 1522 was a possession of the Knights of St. John, who having been driven out of Jerusalem, held the island against the Turks. The fortifications—as you might imagine—will be first on my tour—since they’re close by, and a museum. Double treat!