I had almost started by saying we were touring the “old,” which is the Jade Buddha temple—built in 1928—when I realized we’d visited the Yu Yuan

(the Yu garden) which dates from the 16th century, and spent almost two hours in the Shanghai Museum, where I lingered in the bronzes, some of which go back to 2500 BC, and the beginnings of the Chinese state.

(the Yu garden) which dates from the 16th century, and spent almost two hours in the Shanghai Museum, where I lingered in the bronzes, some of which go back to 2500 BC, and the beginnings of the Chinese state.

I’ll be perverse and stick with my first thought, because “old” tends to be no later than the early 20th century, especially in the area where we are  located. Our guide said there are 3 working Buddhist temples in Shanghai (population 23 million), and the Jade Buddha is the most visited. One (and this is so PRC) was moved to make way for a metro station and reconstructed. The third one is quite a distance from the Bund, but was featured in a lot of postcards from a hundred years ago. We passed it once, but our guide pointed out that it was a prison camp area under Japanese occupation, and thus is not on most tour agendas.

located. Our guide said there are 3 working Buddhist temples in Shanghai (population 23 million), and the Jade Buddha is the most visited. One (and this is so PRC) was moved to make way for a metro station and reconstructed. The third one is quite a distance from the Bund, but was featured in a lot of postcards from a hundred years ago. We passed it once, but our guide pointed out that it was a prison camp area under Japanese occupation, and thus is not on most tour agendas.

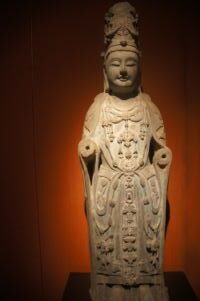

Our guide did one of the best jobs in explaining Buddhism that I’ve had in a long time, and especially the differences between the Buddha, Bodhisattvas, and Arhats. She compared it to Phds, Masters, and College graduates, an analogy I finally understand. The main Bodhisattva (serious disciple who has learned and stayed behind to help people) is the Guan Yin, whose transformation, documented in the Shanghai Museum, and I hope over time at the Buddhist caves I will be seeing in Datong after the students leave. The Guan Yin started as an Indian man (all the Buddhas are male), but I think it was the Empress Wu, the only woman to rule China, who made him into a her. The museum exhibit also (bear in mind that it is a little Sinified) noted that in becoming Chinese (which happens if you’re here long enough, as our students will see in the mosque in Xi’an), it became more compassionate. The Guan Yin is popular especially among women because they pray to her for children.

She was also excellent in explaining the layout of the Buddhist temple—with its halls, drum tower,and bell tower, etc. Our students will get other opportunities in Xi’an to see another temple (an OLD one), and I hope to compare and contrast it with the Tibetan temple in either Beijing or Chengde.

The secular version was the Yu garden, once the centerpiece of the third Shanghai city of the old days—in addition to the French Concession and the International Settlement, there was a Chinese city. The wall around it has long since been torn down, and the rest of the area rebuilt as a “China  town,” but there is no mistaking the wealth of the Pan family which built the garden originally, or the authenticity it represents in furniture, layout, gardening, and especially the juxtaposition of rocks (many with interesting shapes, some piled together to make hills) and ponds—together the characters for mountains and water equal scenery. As one of the students noted, facing a man-made pond filled with huge goldfish and a hill that at one time was the highest in flat Shanghai (it is on the Yangtze River delta), “I could really study for finals here.” It’s one of my favorite places in Shanghai, partly because no matter how crowded it is, the use of space gives you the illusion of solitude—in a city of 23 million people.

town,” but there is no mistaking the wealth of the Pan family which built the garden originally, or the authenticity it represents in furniture, layout, gardening, and especially the juxtaposition of rocks (many with interesting shapes, some piled together to make hills) and ponds—together the characters for mountains and water equal scenery. As one of the students noted, facing a man-made pond filled with huge goldfish and a hill that at one time was the highest in flat Shanghai (it is on the Yangtze River delta), “I could really study for finals here.” It’s one of my favorite places in Shanghai, partly because no matter how crowded it is, the use of space gives you the illusion of solitude—in a city of 23 million people.

The surrounding “Chinatown” offers a wealth of shopping, eating, and other experiences, such as the Temple of God, which is a Taoist (an indigenous religion that has somewhat amalgamated with Buddhism) temple; I’ve bought reproductions of the International Settlement coins there over time, as well as xiao lung bao, a Shanghai dim sum, tea, chopsticks, and lots of whatnot. Every time I think the boundary of gauche has been reached, I go back to the Yu garden area and discover how inventive is the mind of man. Today, the touts were trying to sell us a roller skate that goes on your heel, and has only two wheels. We managed to escape, at least the wheel man, with pocket books intact.

That Shanghai has a museum is in itself a change from the first time I came here—or rather that it’s open is a change. I first saw materials from the Shanghai museum in Chicago when a traveling exhibit came to the Field  Museum (I believe) in the lovefest that followed ping-pong diplomacy. But it was always closed when I started coming to Shanghai. In the 1990s, the Shanghai government (remember, I mentioned it was this period when Zhang Ze-min, who had been mayor of Shanghai, replaced Deng Xiao-ping as China’s leader) built a number of new edifices in People’s Park (which had been the race track in the International

Museum (I believe) in the lovefest that followed ping-pong diplomacy. But it was always closed when I started coming to Shanghai. In the 1990s, the Shanghai government (remember, I mentioned it was this period when Zhang Ze-min, who had been mayor of Shanghai, replaced Deng Xiao-ping as China’s leader) built a number of new edifices in People’s Park (which had been the race track in the International

Settlement). One was the art museum, in the old clock tower; another was the museum, where our guide supplied us with an audio guide. Although I’d been to the museum before, I’d never bothered with the guide. It was very useful in the two exhibits I spent my time in—sculptures and bronzes. In addition, the gift shop is first rate, especially in books. I was a little surprised to see some books for sale which I know in the pre-1990s period would have been banned.

What really showed me the contrast between the old new China and the new new China was a boat trip we took tonight on the Yangtze River. I’ve done the trip, but not recently, and never in the evening. It was unnecessary because there were few lights at night in China, a country notoriously power  poor. And poor as well. The old Bund was lit up now—and there were enough new skyscrapers to confuse Shanghai with Hong Kong, although Hong Kong’s setting is unmistakable. Shanghai doesn’t have the Peak, but it certainly has the location as the financial center and main entry and exit point for the trade from central China along the Yangtze River.

poor. And poor as well. The old Bund was lit up now—and there were enough new skyscrapers to confuse Shanghai with Hong Kong, although Hong Kong’s setting is unmistakable. Shanghai doesn’t have the Peak, but it certainly has the location as the financial center and main entry and exit point for the trade from central China along the Yangtze River.

Speaking of the old and the new, the bus took the old back to the hotel, and the new to Xintiandi, a trendy area, to continue their exploration of Shanghai.