Palaces and Gurus May 9-11

Today’s long day (8o miles in 4 hours—each way!) helped us understand a little bit more about South India. We’re 1070 miles from New Delhi, near 12 degrees latitude, which demonstrates in part that India is a country with size and variety.

We’re in the state of Karnataka, one of 28 states in India. I’ve been told that the state divisions were based on languages (roughly)—which should give you an idea of how many languages there are in India! 14 or so are “official”, and where they are, Hindi is taught as a second language. Certainly, most educated people (and people in the tourist trade) speak English. Kanada is spoken and written here, eh? I can’t read it, but the script looks different than Hindi (which I also can’t read).

Here, the crops are rice, coconuts, and silkworms. The state runs wholesale centers for cocoons ( we’ll probably see them somewhere in our trip in China) and coconuts, which we passed on the journey from Bangalore to Mysore. We also passed a number of textile factories, with workers, mostly women, wearing the clothing that they may be making walking to the factories—as typical in India, colorful.

we’ll probably see them somewhere in our trip in China) and coconuts, which we passed on the journey from Bangalore to Mysore. We also passed a number of textile factories, with workers, mostly women, wearing the clothing that they may be making walking to the factories—as typical in India, colorful.

we’ll probably see them somewhere in our trip in China) and coconuts, which we passed on the journey from Bangalore to Mysore. We also passed a number of textile factories, with workers, mostly women, wearing the clothing that they may be making walking to the factories—as typical in India, colorful.

we’ll probably see them somewhere in our trip in China) and coconuts, which we passed on the journey from Bangalore to Mysore. We also passed a number of textile factories, with workers, mostly women, wearing the clothing that they may be making walking to the factories—as typical in India, colorful.The highlight for me was probably taking students into my world—the world of yoga. I talked with our guide about the possibility of doing yoga in  Mysore, because I knew (partly from my trip in January) that the area was a hotbed of yoga instruction, and my instructors back home all knew someone who had become a guru by spending time in Ashtanga Ashrams in Mysore. Fortunately, she was able to tie a yoga class with a lunch visit to a farm run by members one of the smaller communities in India. The yoga master appeared on the porch with mats for each of us, and gave about a 45 minute introduction to yoga moves, breathing, and

Mysore, because I knew (partly from my trip in January) that the area was a hotbed of yoga instruction, and my instructors back home all knew someone who had become a guru by spending time in Ashtanga Ashrams in Mysore. Fortunately, she was able to tie a yoga class with a lunch visit to a farm run by members one of the smaller communities in India. The yoga master appeared on the porch with mats for each of us, and gave about a 45 minute introduction to yoga moves, breathing, and  meditation. Who knows, some students may take it up when they return to IWU. The meal was appropriate to the particular community, which numbers 19,000, has its own dialect and clothing, and lives in the mountains farming—including coffee.

meditation. Who knows, some students may take it up when they return to IWU. The meal was appropriate to the particular community, which numbers 19,000, has its own dialect and clothing, and lives in the mountains farming—including coffee.

Mysore, because I knew (partly from my trip in January) that the area was a hotbed of yoga instruction, and my instructors back home all knew someone who had become a guru by spending time in Ashtanga Ashrams in Mysore. Fortunately, she was able to tie a yoga class with a lunch visit to a farm run by members one of the smaller communities in India. The yoga master appeared on the porch with mats for each of us, and gave about a 45 minute introduction to yoga moves, breathing, and

Mysore, because I knew (partly from my trip in January) that the area was a hotbed of yoga instruction, and my instructors back home all knew someone who had become a guru by spending time in Ashtanga Ashrams in Mysore. Fortunately, she was able to tie a yoga class with a lunch visit to a farm run by members one of the smaller communities in India. The yoga master appeared on the porch with mats for each of us, and gave about a 45 minute introduction to yoga moves, breathing, and  meditation. Who knows, some students may take it up when they return to IWU. The meal was appropriate to the particular community, which numbers 19,000, has its own dialect and clothing, and lives in the mountains farming—including coffee.

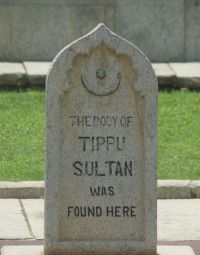

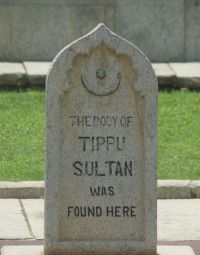

meditation. Who knows, some students may take it up when they return to IWU. The meal was appropriate to the particular community, which numbers 19,000, has its own dialect and clothing, and lives in the mountains farming—including coffee.There is substantial tourism in Bangalore/Mysore, mostly domestic, and we encountered it because the schools are out and this is vacation time; much of it centers on 18th century heroes, the Muslim leaders Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. Hyder was a soldier in the armies of the Maharajah of Mysore, who overthrew the Maharajah and made himself Sultan. The result was a protracted and bitter series of wars in which Hyder, and later Tipu, enlisted French mercenaries, while the deposed Maharajah brought in British forces from the East India Company (British India proper began in 1857, after the British suppressed the Sepoy mutiny and abolished the Honourable Company), while local nabobs like the Nizam of Hyderabad switched sides as it suited them (or to whichever paid best). Hyder and Tipu won the first two wars, and became the great hope to block the growing spread of British rule. As I’ve suggested, this was part of the great world wars between France and Britain that culminated at Waterloo (and included our versions,  the French and Indian War and the American Revolution). Tipu in particular hated the British so much he composed a diary in Persian in which he dreamed of a victory over the British. When one of his nemeses died in battle, Tipu had a toy built—it was a mechanical tiger that devoured a

the French and Indian War and the American Revolution). Tipu in particular hated the British so much he composed a diary in Persian in which he dreamed of a victory over the British. When one of his nemeses died in battle, Tipu had a toy built—it was a mechanical tiger that devoured a  British soldier. When Tipu died in 1799, betrayed when one of his officials, bribed by the British, opened a passageway and let British troops in, the British supposedly drank on the corpse, toasting, “Death to India.” The tiger-toy now reposes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, while millions of Indians toast Tipu. Ironically, he was defeated by troops led by Lord Cornwallis, fresh from his role at Yorktown.

British soldier. When Tipu died in 1799, betrayed when one of his officials, bribed by the British, opened a passageway and let British troops in, the British supposedly drank on the corpse, toasting, “Death to India.” The tiger-toy now reposes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, while millions of Indians toast Tipu. Ironically, he was defeated by troops led by Lord Cornwallis, fresh from his role at Yorktown.

the French and Indian War and the American Revolution). Tipu in particular hated the British so much he composed a diary in Persian in which he dreamed of a victory over the British. When one of his nemeses died in battle, Tipu had a toy built—it was a mechanical tiger that devoured a

the French and Indian War and the American Revolution). Tipu in particular hated the British so much he composed a diary in Persian in which he dreamed of a victory over the British. When one of his nemeses died in battle, Tipu had a toy built—it was a mechanical tiger that devoured a  British soldier. When Tipu died in 1799, betrayed when one of his officials, bribed by the British, opened a passageway and let British troops in, the British supposedly drank on the corpse, toasting, “Death to India.” The tiger-toy now reposes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, while millions of Indians toast Tipu. Ironically, he was defeated by troops led by Lord Cornwallis, fresh from his role at Yorktown.

British soldier. When Tipu died in 1799, betrayed when one of his officials, bribed by the British, opened a passageway and let British troops in, the British supposedly drank on the corpse, toasting, “Death to India.” The tiger-toy now reposes in the Victoria and Albert Museum, while millions of Indians toast Tipu. Ironically, he was defeated by troops led by Lord Cornwallis, fresh from his role at Yorktown.We saw two of Tipu’s summer palaces, one near Mysore which was occupied by Arthur Wellesley, better known as the Duke of Wellington, who cut his teeth in India before chomping Napoleon; the  other was in Bangalore. Both were fine examples of Islamic art, with the arches, open air sections, with some explanations about Tipu and his wars with the British.

other was in Bangalore. Both were fine examples of Islamic art, with the arches, open air sections, with some explanations about Tipu and his wars with the British.

other was in Bangalore. Both were fine examples of Islamic art, with the arches, open air sections, with some explanations about Tipu and his wars with the British.

other was in Bangalore. Both were fine examples of Islamic art, with the arches, open air sections, with some explanations about Tipu and his wars with the British.The other major attraction of Mysore is the palace, built by the Wodeyar family, the rulers of Mysore whom Hyder Ali had shoved aside. Restored to the throne by the British (whose resident built an equally magnificent colonial building) , the Maharajah has an Indo-Saracen palace which is open to the public. The family lost most of their privileges in 1947, when the new Indian government stripped the princely states of political power, though leaving them with some privileges, which were further reduced in the 1970s. The Maharajah and his family still live in the  palace, but as I said, have opened up large areas to the public, including what used to be the public assembly hall, which in size and decoration rivals palaces in Europe. It is said that the Maharajah burned down its predecessor in 1897 because he wanted the opportunity to rebuild. It has lots of carved teak features, inlaid gold and silver doors, chandeliers imported

palace, but as I said, have opened up large areas to the public, including what used to be the public assembly hall, which in size and decoration rivals palaces in Europe. It is said that the Maharajah burned down its predecessor in 1897 because he wanted the opportunity to rebuild. It has lots of carved teak features, inlaid gold and silver doors, chandeliers imported from Europe, and a display of possessions that includes an 80 kg gold howda for riding the royal elephant and a 200 kg gold throne.

from Europe, and a display of possessions that includes an 80 kg gold howda for riding the royal elephant and a 200 kg gold throne.

palace, but as I said, have opened up large areas to the public, including what used to be the public assembly hall, which in size and decoration rivals palaces in Europe. It is said that the Maharajah burned down its predecessor in 1897 because he wanted the opportunity to rebuild. It has lots of carved teak features, inlaid gold and silver doors, chandeliers imported

palace, but as I said, have opened up large areas to the public, including what used to be the public assembly hall, which in size and decoration rivals palaces in Europe. It is said that the Maharajah burned down its predecessor in 1897 because he wanted the opportunity to rebuild. It has lots of carved teak features, inlaid gold and silver doors, chandeliers imported from Europe, and a display of possessions that includes an 80 kg gold howda for riding the royal elephant and a 200 kg gold throne.

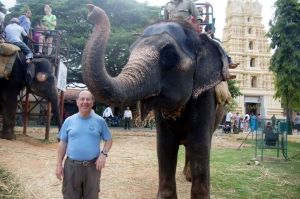

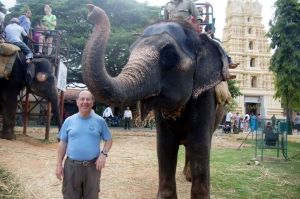

from Europe, and a display of possessions that includes an 80 kg gold howda for riding the royal elephant and a 200 kg gold throne.One of the businesses that has sprung up offers the opportunity to ride elephants around the grounds. Of course, it was something we had to do. I could only imagine going into battle on one of these beasts as we swung and swayed—rather like riding the bus on the 80  mile ride from Mysore to Bangalore. One of the reasons it took 4+ hours was the construction in Bangalore of a metro system. The other was the fact that the highway goes through every town, and to make people slow down, has speed bumps and a series of barriers that you have to dodge around.

mile ride from Mysore to Bangalore. One of the reasons it took 4+ hours was the construction in Bangalore of a metro system. The other was the fact that the highway goes through every town, and to make people slow down, has speed bumps and a series of barriers that you have to dodge around.

mile ride from Mysore to Bangalore. One of the reasons it took 4+ hours was the construction in Bangalore of a metro system. The other was the fact that the highway goes through every town, and to make people slow down, has speed bumps and a series of barriers that you have to dodge around.

mile ride from Mysore to Bangalore. One of the reasons it took 4+ hours was the construction in Bangalore of a metro system. The other was the fact that the highway goes through every town, and to make people slow down, has speed bumps and a series of barriers that you have to dodge around.We toured Bangalore today after an interesting talk from a real estate agent from Jones Lang, and LaSalle, an American firm based in Chicago that manages corporate headquarters (among other businesses) for companies like Dell. He pointed out that India’s conservative financial system spared it the Western meltdown. Our observations tend to concur. Spending an hour or so on “Commercial Street,” fostered the belief that consumerism is alive and well. So did our dinner at a mall that housed the high-end brands.

I’m writing this at 2 am, awaiting our flight to Hong Kong with some regret at leaving India. I’ll miss my dosa breakfasts, but am leaving with both good memories and a belief I did not have years ago of progress. One quick vignette: on the road to the airport, indeed, within the airport, the road had speed bumps and a series of screens to slow down traffic. We could not have had a greater contrast when we arrived early the next day (it’s a 3000 mile trip to Hong Kong from Bangalore) at the Hong Kong airport. Once we got on the bus and zoomed to our hotel in Kowloon, the infrastructure contrast between Hong Kong and India could not have been more apparent.

They say business (if not life) is about relationships, and for the India part of our trip, I’m glad Sambit went to IWU and had me for class, and that I went to India in January. Anup Nair at that time not only became a good friend, but a trusted travel agent, who made for an outstanding visit in India, which is, happily, more than infrastructure!