Another long day in the world Yongle created.

One way to look at Beijing is from the perspective of its builders, beginning with Yongle. The third Ming emperor, Yongle moved his capital from Nanking to Beijing, partly to be in a better position to combat the ambitions of the barbarians from the North; ultimately, he was right—it was the Manchus from north of the Great Wall that replaced the Ming in 1644. I think there were other reasons, involving family intrigue, that prompted the decision, but Beijing has never been the same.

Yongle built three of the memorable constructs that have defined Beijing since. We’ve already mentioned two—the Temple of Heaven and the Forbidden City, early in the 15th century. Just in case I don’t get another opportunity to visit the Forbidden City, when I got up this morning I took a

walk to my favorite morning park in Beijing—Coal Hill. It’s typical of the Beijing parks, being full of youngsters my age doing stretching, and younger Beijingers doing everything from taiqi to calligraphy to line dancing. And since it was once part of the Forbidden City, it was a playground for the emperor, and that’s what differentiates it from many other parks. It was the beneficiary of the Emperor’s desire to have a nearby mountain other than the rock pile from Tai Hu. As a consequence, the million workers who built the Forbidden City for Yongle saved the dirt from the moat and piled it up into Coal Hill, a 300 foot mountain at the north end of the Forbidden City. If you’ve seen pictures of that palace, looking down on the 9999 rooms, you probably know the view from Coal Hill.

walk to my favorite morning park in Beijing—Coal Hill. It’s typical of the Beijing parks, being full of youngsters my age doing stretching, and younger Beijingers doing everything from taiqi to calligraphy to line dancing. And since it was once part of the Forbidden City, it was a playground for the emperor, and that’s what differentiates it from many other parks. It was the beneficiary of the Emperor’s desire to have a nearby mountain other than the rock pile from Tai Hu. As a consequence, the million workers who built the Forbidden City for Yongle saved the dirt from the moat and piled it up into Coal Hill, a 300 foot mountain at the north end of the Forbidden City. If you’ve seen pictures of that palace, looking down on the 9999 rooms, you probably know the view from Coal Hill.

I had it this hazy morning (most mornings in Beijing are hazy). From the top, you can also see nearby Beihai, remnants of the Mongol rule from Beijing, the Drum Tower and Bell Tower that once welcomed the day and signaled the night and the closing of the gates, and the original location of Beijing University, from which angry students marched on May 4, 1919 when they learned that the powers at Versailles had given Japan rights in China. That uprising provided the climate in which the seeds of communism were planted, making it one of the signal events in modern Chinese history. Every major Chinese city has a Wusi (5/4 or May 4) street in commemoration.

The other standard Yongle established was the building of tombs. He chose a site near Beijing with good feng shui, mountains at the back, river at the front, and planned his tomb with the thoroughness he planned the Forbidden City. He laid out the Sacred Way, the stone figures that lined the path that the burial procession trod, with the servants and animals guarding the Emperor’s journey into the nether world—then proceeded to set the standard for the subsequent tombs of his successors. This being a Confucian society, the emperor considered it disrespectful to be more outlandish than his father. In Yongle’s case, the result was the largest extant wood structure (no nails, the guide stressed) in China. The building, which once housed relics of the one tomb excavated (the result of which was the oxidation and disappearance of fabrics and other things in the tombs, prompting a decision not to open any more tombs until the technology improves), now also contains a history of the life of Yongle. Among other things, he sent the famous expeditions of Zheng Ho, which established China as a seapower.

The other standard Yongle established was the building of tombs. He chose a site near Beijing with good feng shui, mountains at the back, river at the front, and planned his tomb with the thoroughness he planned the Forbidden City. He laid out the Sacred Way, the stone figures that lined the path that the burial procession trod, with the servants and animals guarding the Emperor’s journey into the nether world—then proceeded to set the standard for the subsequent tombs of his successors. This being a Confucian society, the emperor considered it disrespectful to be more outlandish than his father. In Yongle’s case, the result was the largest extant wood structure (no nails, the guide stressed) in China. The building, which once housed relics of the one tomb excavated (the result of which was the oxidation and disappearance of fabrics and other things in the tombs, prompting a decision not to open any more tombs until the technology improves), now also contains a history of the life of Yongle. Among other things, he sent the famous expeditions of Zheng Ho, which established China as a seapower.

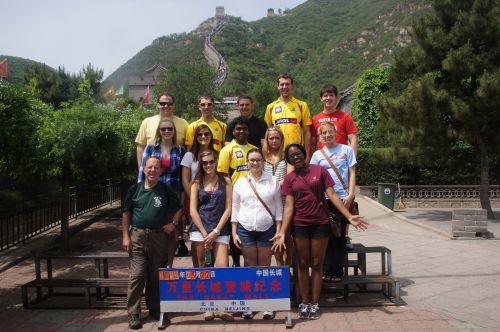

Yongle was not responsible for the Great Wall, but the Great Wall we have come to know was a product of the Ming dynasty, which, as I said, lived in fear of invasion from the north. The Ming resurrected a defense system that predated even Qin Shi-huang, the first emperor, who consolidated the wall his predecessors had built. The Ming wall ran over 4,000 miles, from Shanhaiguan, where it met the sea to Jiayuguan, where it extends into the desert. The stretch we climbed was within 30 miles of Beijing (if you think about the possibility of invasion from the north, bear in mind that’s the distance from Seoul to the 38th parallel in Korea), the product, I think of the post-Mao dynasty, which has been building tourist attractions like crazy.

Yongle was not responsible for the Great Wall, but the Great Wall we have come to know was a product of the Ming dynasty, which, as I said, lived in fear of invasion from the north. The Ming resurrected a defense system that predated even Qin Shi-huang, the first emperor, who consolidated the wall his predecessors had built. The Ming wall ran over 4,000 miles, from Shanhaiguan, where it met the sea to Jiayuguan, where it extends into the desert. The stretch we climbed was within 30 miles of Beijing (if you think about the possibility of invasion from the north, bear in mind that’s the distance from Seoul to the 38th parallel in Korea), the product, I think of the post-Mao dynasty, which has been building tourist attractions like crazy.

The section we visited was reputedly the steepest reconstruction, and it elevates about 700 feet in less than a mile—someone said a 45 degree angle, and having done it, I’m inclined (there’s a pun here) to agree. In places it’s three people wide at most, and as crowded as Beijing highways (even with the banning of 1/5 of the cars each day, driving in Beijing is a challenge! The Beijing government has restricted the purchase of new cars to 20,000 a month, with a lottery auction that sometimes reaches $20,000 US for the right to buy a car! Public transportation is numerous, with 20,000 natural gas busses, and 13 metro lines, with a fee of roughly 30 cents!) Half the population of China was on our section, and I wonder how horses and warriors could have gotten up the stairs. In any case, in 1644, when peasants rose in rebellion in response to famine (the Emperor was supposed to provide social stability, even then—defined as prosperity at home and prestige abroad, then and now!), the Manchus bribed one of the gatekeepers at the wall to open the gates, and the rest was history—Manchu history.

One the way home, we visited the Olympic village, an area cleared (the Dao temple was left, but unfortunately was closed), and then lavished with public funds for China’s coming out party (the party for the Party) in 2008. I’d been by it before, but had never walked

One the way home, we visited the Olympic village, an area cleared (the Dao temple was left, but unfortunately was closed), and then lavished with public funds for China’s coming out party (the party for the Party) in 2008. I’d been by it before, but had never walked around. It’s situated in the center of the city—exactly north of the Forbidden City, with a plaza that rivals Tiananmen Square, and buildings that are so much the modern equivalent of the Yongle architecture, especially the Bird’s Nest and the Water Cube that I asked our guide if the old palace is GuGong (old palace), is the Olympic Village the XinGong (new palace). Yongle would be proud of this new addition to the city of Beijing.

around. It’s situated in the center of the city—exactly north of the Forbidden City, with a plaza that rivals Tiananmen Square, and buildings that are so much the modern equivalent of the Yongle architecture, especially the Bird’s Nest and the Water Cube that I asked our guide if the old palace is GuGong (old palace), is the Olympic Village the XinGong (new palace). Yongle would be proud of this new addition to the city of Beijing.

It is one of the great ironies (and you know I love ironies) that having built the buildings, the Chinese government is trying to figure out what to do with them. For its debutante role, the government spent extravagantly; the Zhang Yi-mou opening number cost more than was spent on education in the entire country in 2008! The story is that the Bird’s Nest will be converted into a shopping mall, though the outside will remain as it is. That’s so New New China. After all, the man who launched it in the 1980s is Deng Xiaoping, sometimes pronounced done shopping.