I am beginning to understand why 6 million visitors choose to come to Cappadocia. Part of it is the weather—at least in the 7 months of the year when it’s not snow covered. We’re at 4,000 feet, which makes evenings temperate (in the 50s), with warm days (in the 80s), and apparently it’s like  this until the snows come—and it gets bitterly cold, our guide says, with lots of snow. Some of that is obvious when I look out my window at the volcano largely responsible for the eruptions that created Cappadocia—it’s over 4000 meters, or over 12,000 feet, still snowcapped, and betraying that volcano shape that hides the fact that the last eruption was 2 million years ago, and the guide assured me it was dormant.

this until the snows come—and it gets bitterly cold, our guide says, with lots of snow. Some of that is obvious when I look out my window at the volcano largely responsible for the eruptions that created Cappadocia—it’s over 4000 meters, or over 12,000 feet, still snowcapped, and betraying that volcano shape that hides the fact that the last eruption was 2 million years ago, and the guide assured me it was dormant.

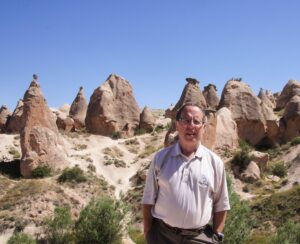

The second attraction may well be the scenery. As I mentioned, it’s a combination of the Badlands, Wyoming, Zion-Bryce, and maybe the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park because it is pretty green in some places. The volcano created lava flows and a variety of rocks and minerals  that have eroded in various ways; the scenery consists of “fairy chimneys” and rock formations that could be in the Great Sand Dunes, hoodoo type formations with balanced rocks on top; I think the description of one valley is “like the moon,” and another is called imagination valley, where our guide was able to point out formations that looked like “Napoleon’s Hat,” etc.

that have eroded in various ways; the scenery consists of “fairy chimneys” and rock formations that could be in the Great Sand Dunes, hoodoo type formations with balanced rocks on top; I think the description of one valley is “like the moon,” and another is called imagination valley, where our guide was able to point out formations that looked like “Napoleon’s Hat,” etc.

Probably the third reason—though not in my order of importance—is the human history of the place. If I were to go to the museum in Kayseri, the main place, I’d probably find evidence of settlement for at least 4000 years,  including the Hittites (can the Sox get one to bat!), whose legacy is partly in the pottery the locals reproduce and sell to Scout leaders who are enjoying their first trip to Cappadocia. Then the Persians were through here, and we’re far enough east to have the Persian armies tramp through here several times on their way to fight the Greeks or the Romans.

including the Hittites (can the Sox get one to bat!), whose legacy is partly in the pottery the locals reproduce and sell to Scout leaders who are enjoying their first trip to Cappadocia. Then the Persians were through here, and we’re far enough east to have the Persian armies tramp through here several times on their way to fight the Greeks or the Romans.

Most of the ruins, however, date from the Roman/Byzantine period—from the 3rd century AD until the area was conquered in the 13th century by first the Seljuk Turks and then the Ottomans. During that period, for some reason, Christianity took root in Cappadocia, and most of what we looked at today was what remained from that period. Because the rock could be worked relatively easily, people made homes in the caves—in  fact, the guest house where I’m staying is a modified cave house. They created whole villages in the “fairy chimneys,” rather like the Puebloan in the Southwest—except the homes were individual, and not communal, though we did see some communal kitchens. Like the native Americans at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, the

fact, the guest house where I’m staying is a modified cave house. They created whole villages in the “fairy chimneys,” rather like the Puebloan in the Southwest—except the homes were individual, and not communal, though we did see some communal kitchens. Like the native Americans at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, the  Cappadocians could clamber up the staircases to their cave homes and wait out the invasion. The churches–bear in mind that people were illiterate–had to be decorated with scenes from the bible for education. The frescos were painted in natural ingredients, including pigeon white (I said they created dovecotes so they could get dove manure to fertilize the vineyards), and because the caves were covered (apparently, this area is not susceptible to earthquakes), many of the frescoes survived both time and the Muslim conquest; because Muslim art does not feature people (at least not in mosques), the Muslims tended to deface (literally) the frescoes, but

Cappadocians could clamber up the staircases to their cave homes and wait out the invasion. The churches–bear in mind that people were illiterate–had to be decorated with scenes from the bible for education. The frescos were painted in natural ingredients, including pigeon white (I said they created dovecotes so they could get dove manure to fertilize the vineyards), and because the caves were covered (apparently, this area is not susceptible to earthquakes), many of the frescoes survived both time and the Muslim conquest; because Muslim art does not feature people (at least not in mosques), the Muslims tended to deface (literally) the frescoes, but  there were still some magnificent churches, partly because of the importance of Cappadocia in church history. I had Eusebius as bishop of Caesarea, which he was—in Palestine—but there were three local Saints that were featured in the churches here.

there were still some magnificent churches, partly because of the importance of Cappadocia in church history. I had Eusebius as bishop of Caesarea, which he was—in Palestine—but there were three local Saints that were featured in the churches here.

I’m glad to be one of the 6 million visitors this year, but I do hope they’re not all 6 million will be here tomorrow.