They say you can’t do everything in 3 ½ days in Beijing, but I think we’ve come as close as possible to exploring this majestic center of the center of the Universe. We’ve joined 19 million residents (it’s China’s third largest city, behind Chongqing and Shanghai), who all seemed to be on the subway tonight, 5 million-plus cars (so many that certain license numbers—today those ending in 5 or 0—are banned, though it’s hard to tell what 20% less means), and hordes of tourists.

They say you can’t do everything in 3 ½ days in Beijing, but I think we’ve come as close as possible to exploring this majestic center of the center of the Universe. We’ve joined 19 million residents (it’s China’s third largest city, behind Chongqing and Shanghai), who all seemed to be on the subway tonight, 5 million-plus cars (so many that certain license numbers—today those ending in 5 or 0—are banned, though it’s hard to tell what 20% less means), and hordes of tourists.

The capital of China since the Yongle emperor of the Ming Dynasty, worried about the barbarians from the north, moved it here in 1406 (from Nanking; it had also been the capital while Kublai Khan and the Mongols ruled for 80 years). Beijing was built to impress, and that it does. The phrase, “Oh My God,” overused (in my opinion, by some of our students) truly applies here. China has historically not only been the most populous country, but at times the richest. Certainly, the 24 Ming and Qing emperors who lived here lived as though they were rich, and they were successful in impressing foreign devils with the might of Chinese civilization—even today. Tourism is the biggest business, and China has both the history and the infrastructure to deliver it, aided by the “coming out party” called the Olympics. One benefit of that extravaganza (China reputedly spent more money on the opening ceremony than the country spent on education that year!) was the moving permanently of a major steel plant, which improved the air quality, noticeably for those of us who haven’t been here for a while.

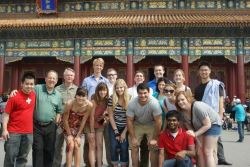

The old Chinese saying, “come and be transformed,” is obvious from the sites we visited. This morning, we assayed the Forbidden City. Even though  only a small part of it is open, it dazzles with length, breadth, and opulence. I can only imagine what it must have been like to be a foreign ambassador and walk through the city (the gates have three openings, one for the emperor, his empress or empresses, and the three top students on the annual imperial exams). If you haven’t seen The Last Emperor, you ought to—it’s a portrayal of the end of the Qing Dynasty. It’s filming in the Palace Museum (what the palace became after Puyi was thrown out in 1924) caused the sacking of the mayor of the city, who allowed foreign cameras to be placed on the buildings, etc. I had to point out the spot where Starbucks had been, evicted after an email campaign unusual for China in that it was bottom up.

only a small part of it is open, it dazzles with length, breadth, and opulence. I can only imagine what it must have been like to be a foreign ambassador and walk through the city (the gates have three openings, one for the emperor, his empress or empresses, and the three top students on the annual imperial exams). If you haven’t seen The Last Emperor, you ought to—it’s a portrayal of the end of the Qing Dynasty. It’s filming in the Palace Museum (what the palace became after Puyi was thrown out in 1924) caused the sacking of the mayor of the city, who allowed foreign cameras to be placed on the buildings, etc. I had to point out the spot where Starbucks had been, evicted after an email campaign unusual for China in that it was bottom up.

I’ve walked in the mornings, which is a great time to be up and about (the People’s Liberation Army unit housed in the Forbidden City hoists the flag at sunrise—4:51 this morning when a few of us got to watch it), and I’ve found parks that used to be part of the Imperial Court.  On one side, what used to be the ancestral tablets and shrine is now a workers’ cultural palace, which has all the features of the palaces—centuries-old cypress trees in shapes meant to amuse (the Crown prince’s forest was planted by “naughty and playful” princes who planted them randomly), huge rocks in fantasy shapes, walls, buildings resplendent in red and gold—and no tourists. The other side is dedicated to Dr. Sun Yat-sen, but was also an imperial playground. I sought to explore more on the west side of the Palace when I rented a bicycle one evening, only to be warned by the army on guard that I was getting close to Zhongnanhai, the home of the chief party officials; the new emperors who replaced the old.

On one side, what used to be the ancestral tablets and shrine is now a workers’ cultural palace, which has all the features of the palaces—centuries-old cypress trees in shapes meant to amuse (the Crown prince’s forest was planted by “naughty and playful” princes who planted them randomly), huge rocks in fantasy shapes, walls, buildings resplendent in red and gold—and no tourists. The other side is dedicated to Dr. Sun Yat-sen, but was also an imperial playground. I sought to explore more on the west side of the Palace when I rented a bicycle one evening, only to be warned by the army on guard that I was getting close to Zhongnanhai, the home of the chief party officials; the new emperors who replaced the old.

Three other imperial sites reinforced the awesomeness of the middle  kingdom and its all-powerful emperor. One was the tombs. Tourists usually go to the Ming tombs since they’re on the way to the Great Wall at Badaling. Here, the Mings buried 13 of their emperors in a valley whose entrance is guarded by the “Sacred Way,” animals and officials in pairs, one resting, one serving the needs of the emperor, to serve him in the afterlife. The tomb-type construction predates the Mings, at least as far back as the Qin Dynasty, 200 BC, whose emperor (the first emperor) unified China and gave his name to the country; his tombs have the terra cotta warriors etc. I’ve also been to Korea for a visit to King Sejong, who created the Korean language, and his tomb is a smaller version of the Chinese (but he was a king, not an emperor), and also to the tombs in Hue, which again reflect the notion of what it meant to be imperial in Asia—copy the model.

kingdom and its all-powerful emperor. One was the tombs. Tourists usually go to the Ming tombs since they’re on the way to the Great Wall at Badaling. Here, the Mings buried 13 of their emperors in a valley whose entrance is guarded by the “Sacred Way,” animals and officials in pairs, one resting, one serving the needs of the emperor, to serve him in the afterlife. The tomb-type construction predates the Mings, at least as far back as the Qin Dynasty, 200 BC, whose emperor (the first emperor) unified China and gave his name to the country; his tombs have the terra cotta warriors etc. I’ve also been to Korea for a visit to King Sejong, who created the Korean language, and his tomb is a smaller version of the Chinese (but he was a king, not an emperor), and also to the tombs in Hue, which again reflect the notion of what it meant to be imperial in Asia—copy the model.

The second imperial site was the Temple of Heaven, which Beijing uses as  its logo. With good reason. This imposing edifice also exists at the north end of a long walkway, where various preliminaries occurred before the emperor prayed for a good harvest (which provided job security!). If you think about a country based on agriculture, you realize that having a good harvest was important. Part of the wisdom the Jesuits brought to the Orient was their knowledge of Western science and astronomy, which intrigued the Chinese enough to allow the Jesuits to convert Chinese to Christianity.

its logo. With good reason. This imposing edifice also exists at the north end of a long walkway, where various preliminaries occurred before the emperor prayed for a good harvest (which provided job security!). If you think about a country based on agriculture, you realize that having a good harvest was important. Part of the wisdom the Jesuits brought to the Orient was their knowledge of Western science and astronomy, which intrigued the Chinese enough to allow the Jesuits to convert Chinese to Christianity.

The third “must see” is the Great Wall. The current version recreates the  Qing great wall, although a wall protecting China from northern barbarians (and keeping Chinese in) predates the first emperor, one of whose accomplishments was to consolidate the existing walls. A business run by the City of Beijing, it has some of the most persistent hawkers in China. Steep, it never really kept out the barbarians or kept in the Chinese, but it’s a magnet for tourists.

Qing great wall, although a wall protecting China from northern barbarians (and keeping Chinese in) predates the first emperor, one of whose accomplishments was to consolidate the existing walls. A business run by the City of Beijing, it has some of the most persistent hawkers in China. Steep, it never really kept out the barbarians or kept in the Chinese, but it’s a magnet for tourists.

We also learned a lot about doing business here at our visit to Caterpillar, a $40 billion company (doubled in the last five years). I thought it was interesting when our three speakers noted they’d been with the company no more than 3 years. From what they said, there is a lot of competition for  skilled labor in China; they have 90 positions which have not been filled for a year. Competition is so stiff that 30% pay increases have to be offered as an inducement. “Talents are assets,” one said, “not people.” Cat has had a presence in China since the 1970s, and seeks to get more business from China, which is the world’s biggest market for certain of its products. What they said, though, was that China is a price market, and Cat is 20% more expensive than Japanese rival Komatsu, and 50% more expensive than Chinese products. Consequently, Cat gets only 10% if its sales from China. The company has introduced a GPS technology which tells where the equipment is located; it sounds like sometimes equipment in arrears has vanished. The other lesson was about doing business with State Owned Enterprises, which many of Caterpillar’s customers are. The company has hired someone with military experience who went to study public policy in the United States, and returned to head a program emphasizing corporate governance. In other words, someone who can navigate the bureaucracy. She noted that China is top down, where the United States is bottom up. Her point was that the rules of engagement are changing, from an export-driven economy to one that wants high tech and management skills, and stressed the idea of being a good corporate citizen.

skilled labor in China; they have 90 positions which have not been filled for a year. Competition is so stiff that 30% pay increases have to be offered as an inducement. “Talents are assets,” one said, “not people.” Cat has had a presence in China since the 1970s, and seeks to get more business from China, which is the world’s biggest market for certain of its products. What they said, though, was that China is a price market, and Cat is 20% more expensive than Japanese rival Komatsu, and 50% more expensive than Chinese products. Consequently, Cat gets only 10% if its sales from China. The company has introduced a GPS technology which tells where the equipment is located; it sounds like sometimes equipment in arrears has vanished. The other lesson was about doing business with State Owned Enterprises, which many of Caterpillar’s customers are. The company has hired someone with military experience who went to study public policy in the United States, and returned to head a program emphasizing corporate governance. In other words, someone who can navigate the bureaucracy. She noted that China is top down, where the United States is bottom up. Her point was that the rules of engagement are changing, from an export-driven economy to one that wants high tech and management skills, and stressed the idea of being a good corporate citizen.

China views its “modern history,” as the monument on Tienanmen Square indicates, beginning in 1840 with the Opium War. It is the current administration’s goal to restore the glory that was China, and from what I’ve seen in the last 21 years, has come a long way toward meeting that goal.