Two quotes infuse today’s blog. The first is Carolyn’s exclamation: “You’re not making them take four train rides, are you?” Well, no. It’s five, as one of the students pointed out, but the last one—hopefully the one they’ll remember best—was both the longest and on the most comfortable train.

We left Hong Kong about 3:30 in the afternoon (after another torrential rain in the morning, and another wonderful meal with my friend, Eleanor; this one was a dim sum in another upstairs restaurant with no English speakers, no English menu, and no tourist prices, with Carrie and the two students who wanted the experience) for the 23-hour train ride to Beijing. The train was non-stop, meaning we cleared customs in Hong Kong, but did not have to face the temperature gun—literally—until we arrived 23 hours later in the capital of the People’s Republic of China.

We had four-person compartments that were sleepers, and I was probably the only one of the group who did not take advantage of the opportunity to sleep for 20 hours. Instead, I was up early, watching the miles roll by (at times we reached 150 km/h–so said the train marquee, though it said we were going 82 km/h when we were standing in the station) and I saw us cross the Yellow River (China’s sorrow, which looked like it was shy of water; I later saw it was down 13% from the previous year, reflecting the drought that has afflicted north China for many years) and go through Zhengzhou, a big rail junction and one of the ancient cities I visited three years ago.

We shifted from rice to wheat, but everywhere we saw at least two things: incredible infrastructure spending on superhighways (China has really encouraged the purchase of automobiles, unlike Singapore and Vietnam, for example, which have limited license to purchase auctions, once up to $50,000 Singaporean, now down to $8,000), and high tariffs for Singapore, and high tariffs for Vietnam. (See the cover story about Shanghai: the New Detroit in Newsweek). We noted people in the fields. If you go from Bloomington to Chicago, you never see anyone in the fields unless it is harvest time or planting time. Rice fields especially require a lot of labor. One of the books I finished on the trip was Malcolm Caldwell’s The Outliers, which has a chapter on rice versus other farming, and on math, which helps explain the Chinese work ethic.

So yes, we did have another train ride, but I think it was one everyone enjoyed; recharged batteries will help them in the rigors we have planned in Beijing.

The second part of this blog comes with a quote from J.R. Glenn, a 2005 graduate of IWU who joined us yesterday around midnight. He and I have travelled to Burma and Tibet, and when I suggested Mongolia for this year, he promptly agreed. When we got in from our Peking Opera last night, he was standing in line to check in, his plane having arrived an hour-plus early. “I’m home,” he told me, and it occurred to me that in some ways, I am, too.

Like everywhere we’ve been on this trip, we have too little time in this capital of the world’s largest country in terms of population. I say that about Beijing because I know what one can do here, and I’m doing my best to make sure we do as much as we can in the time we’re here. I’m happy to say we have the best guide we’ve had anywhere (not always the case in this city), and she and I sat down when we got in and talked about what we might be able to do. She’s managed to make most of my requests into can-dos (in return for which I told her we’d do the “factory visits” we didn’t have to do, but she gets credit for taking us to them. I understand how tourism works better than most trip leaders, and I want to see her get the good marks she’s earned with us).

Our days start early and end late. Certainly our day and a half in Beijing fit that description. When we got in, we had a short turnaround time before our trip to the Qingmen Hotel for a brief introduction to Peking Opera (if you  want to know more, rent Farewell My Concubine, by Zhang Yi Mou). A brief introduction is usually enough for foreigners, although the program had more acrobatics than singing. The second number featured the monkey king (a figure common in Buddhist/Hindu lands), and some really funny aspects and some spectacular acrobats.

want to know more, rent Farewell My Concubine, by Zhang Yi Mou). A brief introduction is usually enough for foreigners, although the program had more acrobatics than singing. The second number featured the monkey king (a figure common in Buddhist/Hindu lands), and some really funny aspects and some spectacular acrobats.

When that let out, some of the students decided to walk back to the hotel, but the guide offered to take anyone who wanted to go to Ah Fun Ti, a Xinjiang restaurant that features Hui (Muslim) foods that I’ve had in Xinjiang. About half of us showed up at the restaurant (which has a floor show including belly dancing) just in time to see the end of the show. We ate, and I asked if the manager would start the belly dancing. Instead, he turned on the music, the musical ball, and Whitney Durham and I started dancing, and by the time we were done, the restaurant staff was on the stage with all our students and the few remaining patrons in what could have been dancing, but a good time was certainly had by all.

Today was another busy day. It started with a 6:30 wake up call, and an 8 o’clock departure for another spectacular place that most of the group had read about, but never been to—the Forbidden City. As many times as I’ve been to it, I’m still in awe. Built by the second or third Ming Emperor by 1420, and about to celebrate its 600th birthday, the palace was home to 14 emperors until the 1911 revolution abolished the monarchy. It’s been a public spectacle since the 1920s, when Pu-yi (known as the last emperor even though there was an attempt by Yuan Shih-kai to name himself emperor for 86 days in 1916), was evicted, I think by a warlord. Pu-yi went on to flirt with the Japanese who made him their emperor of Manchukuo in the 1930s.

We didn’t see many of the 9,999 rooms (a room being defined as the space between 4 pillars, but there’s still a lot of our kind of rooms) although we walked from the southern entrance (Tiananmen, the gate of heavenly peace) to the north. The palace has been refurbished, partly for the Olympics, partly with an eye on the 2020 celebration sure to come, at a cost of several billion dollars, and I didn’t see the faded or peeling paint so common in the past, and the Starbucks that was once in the City has been evicted (as a result of an Internet campaign!), but I did see the mobs of tour groups that prove, once again, tourism is the world’s biggest business. From south to north, we went from impressive public gathering places to the Throne room to the private quarters where the royal family (the emperor had around 3,000 cohorts; he chose his 2-hour companions by drawing their names from bamboo). The new emperors live in a part of the Forbidden City that is, well, forbidden!

We were able to do something I’ve never done with a tour before, but has always been one of the highlights of the city for me—a climb of Coal Hill in a park across the street (now) from the Forbidden City. Builders of the moat dumped the dirt they excavated in a pile which became Coal Hill, a royal playground overlooking the Forbidden City. I convinced our guide it was a good idea to go there, and we got the best views of the entire layout possible without an airplane.

From the Forbidden City, we went to a local area nearby, a “hutong,” the small alleyways where 3

From the Forbidden City, we went to a local area nearby, a “hutong,” the small alleyways where 3 generations of families live in a square compound that is a little version of the Forbidden City, where we had lunch with a local family, who’d owned the place for 3 generations. Though the government has torn down 80% of these quaint buildings (which have public but not private washrooms), this area has been spared the wrecker’s ball, and many of the hutongs fronting on the artificial lake have been refurbished as bars and restaurants (hopefully with internal washrooms).

generations of families live in a square compound that is a little version of the Forbidden City, where we had lunch with a local family, who’d owned the place for 3 generations. Though the government has torn down 80% of these quaint buildings (which have public but not private washrooms), this area has been spared the wrecker’s ball, and many of the hutongs fronting on the artificial lake have been refurbished as bars and restaurants (hopefully with internal washrooms).

In the evening, we went to probably the most professionally choreographed show I’ve seen in China, “The Story of Kung Fu,” which made more sense to  me than the last time I saw it because I’ve since visited the Shaolin Monastery, the location of the source of Kung Fu. Many of us got dropped off at Wangfujing (which used to be known as Morrison Street when it was part of the foreigners’ forbidden city); after the Boxer Uprising, the legations and embassies had a wall around them fit for new emperors, and it was as forbidden to ordinary people as the nearby Forbidden City of the emperors. Once a street full of quaint shops (including

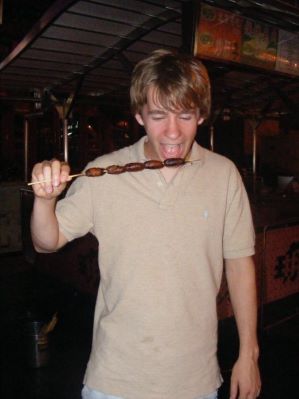

me than the last time I saw it because I’ve since visited the Shaolin Monastery, the location of the source of Kung Fu. Many of us got dropped off at Wangfujing (which used to be known as Morrison Street when it was part of the foreigners’ forbidden city); after the Boxer Uprising, the legations and embassies had a wall around them fit for new emperors, and it was as forbidden to ordinary people as the nearby Forbidden City of the emperors. Once a street full of quaint shops (including  the ancient deer and antler pharmacy, which I think is where linguists discovered the Shang bones that gave them a clue to the origins of Chinese writing), it’s been converted into a shopping mall ala Michigan avenue, name brand stores, etc. There is still a food court there, with hawkers who sell snake, cicadas, scorpions and other creepy crawly things that are not on the usual restaurant menus—nor on anything else.

the ancient deer and antler pharmacy, which I think is where linguists discovered the Shang bones that gave them a clue to the origins of Chinese writing), it’s been converted into a shopping mall ala Michigan avenue, name brand stores, etc. There is still a food court there, with hawkers who sell snake, cicadas, scorpions and other creepy crawly things that are not on the usual restaurant menus—nor on anything else.

I’m going to skip our business visit and some observations of Beijing and China until I get a chance later. We’re off to the Great Wall soon and I want to get this onto e-mail. As I said, we’ve been busy. Sleep when we get home! Oh, that’s right, I’m at home here (almost!) Zaijian.