Fellow Harvard alum and novelist Alec Nevala-Lee (The Icon Thief, City of Exiles, Eternal Empire) recently posted thoughts on “Updike’s Ladder,” whose clichéd meteoric rise “is like lifestyle porn for writers” than more often than not struggle to gain traction in their writing careers or find any meaningful audience for their work. Quoting from the Adam Begley biography, he notes,

Fellow Harvard alum and novelist Alec Nevala-Lee (The Icon Thief, City of Exiles, Eternal Empire) recently posted thoughts on “Updike’s Ladder,” whose clichéd meteoric rise “is like lifestyle porn for writers” than more often than not struggle to gain traction in their writing careers or find any meaningful audience for their work. Quoting from the Adam Begley biography, he notes,

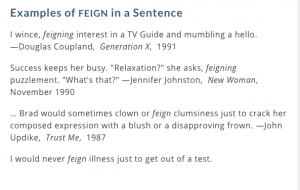

“[Updike] never forgot the moment when he retrieved the envelope from the mailbox at the end of the drive, the same mailbox that had yielded so many rejection slips, both his and his mother’s: ‘I felt, standing and reading the good news in the midsummer pink dusk of the stony road beside a field of waving weeds, born as a professional writer.’ To extend the metaphor . . . the actual labor was brief and painless: he passed from unpublished college student to valued contributor in less than two months.

“If you’re a writer of any kind, you’re probably biting your hand right now. And I haven’t even gotten to what happened to Updike shortly afterward” (again, quoting from Begley):

“A letter from Katharine White [of The New Yorker] dated September 15, 1954 and addressed to ‘John H. Updike, General Delivery, Oxford,’ proposed that he sign a ‘first-reading agreement,’ a scheme devised for the ‘most valued and most constant contributors.’ Up to this point, he had only one story accepted, along with some light verse. White acknowledged that it was ‘rather unusual’ for the magazine to make this kind of offer to a contributor ‘of such short standing,’ but she and Maxwell and Shawn took into consideration the volume of his submissions . . . and their overall quality and suitability, and decided that this clever, hard-working young man showed exceptional promise.

“Updike was twenty-two years old. Even now, more than half a century later and with his early promise more than fulfilled, it’s hard to read this account without hating him a little. Norman Mailer—whose debut novel, The Naked and the Dead, appeared when he was twenty-five—didn’t pull any punches in “Some Children of the Goddess,” an essay on his contemporaries that was published in Esquire in 1963: ‘[Updike’s] reputation has traveled in convoy up the Avenue of the Establishment, The New York Times Book Review, blowing sirens like a motorcycle caravan, the professional muse of The New Yorker sitting in the Cadillac, membership cards to the right Fellowships in his pocket.’ And Begley, his biographer, acknowledges the singular nature of his subject’s rise:

“It’s worth pausing here to marvel at the unrelieved smoothness of his professional path . . . . Among the other twentieth-century American writers who made a splash before their thirtieth birthday . . . none piled up accomplishments in as orderly a fashion as Updike, or with as little fuss. . . . This frictionless success has sometimes been held against him. His vast oeuvre materialized with suspiciously little visible effort. Where there’s no struggle, can there be real art? The Romantic notion of the tortured poet has left us with a mild prejudice against the idea of art produced in a calm, rational, workmanlike manner (as he put it, ‘on a healthy basis of regularity and avoidance of strain’), but that’s precisely how Updike got his start.

Read the entire article.

Updike’s portrayal of Islamism in Terrorist has generally been praised, but a dissenting voice appears in “The (Mis)Representation of Islam in John Updike’s Terrorist,” a critique by research scholar Abdul Haseeb, Dept. of English and Modern European Languages, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, U.P. India that was published in IJELLH, the International Journal of English Language, Literature in Humanities.

Updike’s portrayal of Islamism in Terrorist has generally been praised, but a dissenting voice appears in “The (Mis)Representation of Islam in John Updike’s Terrorist,” a critique by research scholar Abdul Haseeb, Dept. of English and Modern European Languages, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, U.P. India that was published in IJELLH, the International Journal of English Language, Literature in Humanities.