Adam Begley, in Scotland for the Edinburgh International Book Festival, gave an interview to Alan Taylor of The Herald that was assigned the somewhat titillating headline “The final sin of John Updike.”

In the long interview, which was published in the Saturday, August 9 online version, Begley covers a lot of ground and concludes that Updike had given up all but one of his vices—smoking, drinking, sleeping around. “‘It’s true, his last sin was writing,’ says Adam Begley. ‘This compulsion to take other people’s lives and use them for his own ends. Other than that, he had given up naughtiness.'”

Says Begley, “I didn’t think Updike’s biography was difficult to write because my training is in literary criticism and my inclination is towards literary criticism. What Updike offers to me is much more valuable that [Norman Mailer-esque] derring-do or political campaigns; punching one’s colleagues in the faces or biting their ears or stabbing your wife. What he did is write books that drew me to them like a magnet and stories that I could turn to.”

“The character who emerges from Begley’s book is complex and fascinating and, to a degree, elusive,” Taylor writes. “There was, for example, the public figure, who could turn on the charm as one might a light. He was studiedly polite and played the part of literary gent almost to the point of parody. By nature, Updike was also careful and cautious and conservative. For much of his life, moreover, he had a stammer and was plagued with psoriasis. And, having grown up as a single child in a family that always had to count pennies, he could never fall back on privilege.

“But there was also another side to him, observes Begley, that of the daredevil and the practical joker. As a teenager he would woo his pals with stunts, jumping on the running board of his parents’ old black Buick and steering it downhill through the open window. He was prone to tomfoolery, as if determined to draw attention to himself. He liked to leap over parking meters and would through himself downstairs as if he were part of a slapstick act. ‘So there is that contradiction in him,’ says Begley, ‘that is elemental in him and that biographers like and which they pretend they can explain, but can’t.”

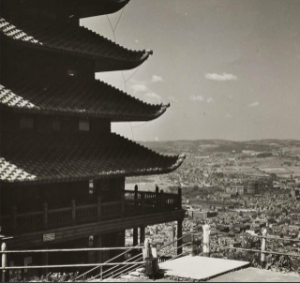

Faulkner had his Yoknapatawpha County, and Steinbeck the Salinas Valley. For Updike it was his boyhood borough of Shillington and the nearby big city of Reading, Pa.

Faulkner had his Yoknapatawpha County, and Steinbeck the Salinas Valley. For Updike it was his boyhood borough of Shillington and the nearby big city of Reading, Pa.