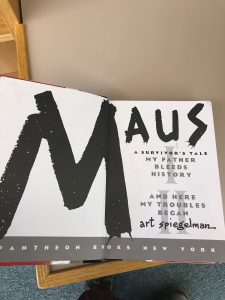

Author(s), Illustrator/Photographer: Art Spiegelman

Publisher and Year Number of pages: Pantheon Books, 1991, 296 Pages.

Genre: Fiction, Autobiography, Memoir, History and Biography.

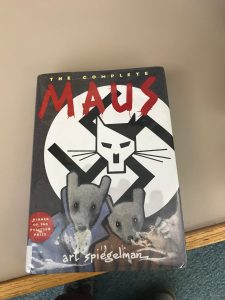

Descriptive Annotation: The cover features two Polish Jews (Spiegelman and his father) cowering under the shadow of a giant swastika, modified by the imposition of a German-stylized cat’s head emblem. This is a combination of both standard Holocaust imagery and the use of animals as metaphors, which can be seen for the entirety of the graphic novel. Maus is the heartbreaking story of a Polish-American man and his aging father’s experiences in the Holocaust as a Polish Jew, and the continued regret of Spiegelman “using” the death of six million Jews to sell his book to some extent in his mind. As the Holocaust is described to him via his father, Spiegelman also continues to express guilt that didn’t talk to his father more about his experiences on a frequent basis when he had the opportunity to do so when the former was alive. The whole of his father’s trials, from growing up in moderately anti-Semitic Poland to the German invasion in 1939 and the ways in which the population react (or don’t react) to the actions the Nazi regime takes against the Jewish population, are covered in the book. Prior knowledge of what the Holocaust was, and perhaps reading of some more traditional fare on the era such as The Diary of Anne Frank, would certainly be useful in the scenario of students reading this novel in the classroom.

Classroom Application: In this graphic novel, the characters are all played by different animal personas based on nationality, which would be ideal for some upper-level social studies settings. For instance, the Nazis/Germans are cats, the Jews are mice, Americans are dogs, and the French are frogs. The metaphors purposefully don’t work for large portions of the story, i.e. when a mouse is a veteran of World War I for Germany and he flickers back and forth between being a mouse and a cat. This is a teachable moment, since it’s Spiegelman’s way of saying that race and racism, or discrimination of any kind, is very arbitrary because the categories we apply really don’t hold water when held up to scrutiny, or when you consider that people can belong to more than one category.

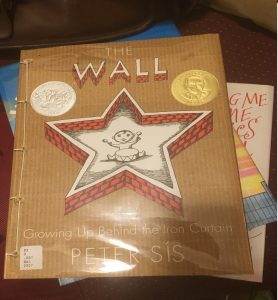

Linguistic and Cultural Diversity Analysis: Spiegelman covers the different ways in which the Holocaust is remembered, and notes that when he published the novel, nobody had used a comic book format to do so before: “I’m not talking about YOUR book now, but look at how many books have already been written about the Holocaust. What’s the point? People haven’t changed…” (Spiegelman, p. 34). Exasperation with people not being able to get the message with traditional mediums of literature drove Spiegelman to write this book, and that is why 27 years later, this is still a widely taught and used piece of work, both in the US and Germany, the latter of which had to be lobbied to permit the public sale of this book due to the display of the swastika being an illegal offense in that country. Another source of controversy is that the animal chosen to represent the Poles was a pig, since that is a common stereotype of people from Poland and from Eastern Europe in general, and the Germans are universally seen as a brutalizing force in the novel as well. The author speaks through one of his characters as unrepentant on the latter, though, stating “Let the Germans have a little what they did to the Jews” (Spiegelman, p. 226). Such an attitude may seem severe to certain readers, but in the context of the experience of Spiegelman’s family and millions of others, it is understandable that they are biased against their erstwhile oppressors and architects of the genocide.